Juelsgaard Clinic Asks California Supreme Court to Preserve Internet Free Speech

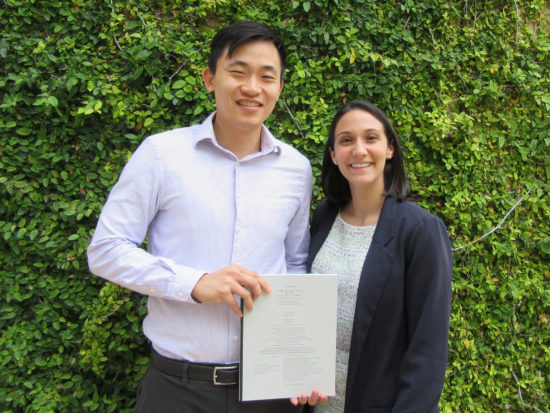

Last week, the Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation Clinic filed an amicus curiae brief urging the California Supreme Court to reverse a California Court of Appeal decision ordering Yelp to remove a negative user review. Clinic students Erica Sollazzo ’17 and Daniel Chao ’18, represented Public Citizen, a non-profit consumer advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C., and Floor64, the company that publishes the online news site Techdirt.com. The brief seeks to overturn the lower court decision that threatens to open a dangerous loophole in § 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a federal law that insulates online intermediaries like Yelp from liability for their users’ speech. Section 230 has played an integral role in shaping the Internet as we know it.

Hassell v. Bird involves a San Francisco lawyer, Dawn Hassell, and a former client, Ava Bird. Dissatisfied with Hassell’s services, Bird wrote a negative review of Hassell’s law firm on Yelp.com. Hassell then sued Bird for defamation and, when Bird did not respond to the complaint, obtained a default judgment. The court awarded Hassell over $500,000 in damages and ordered Bird to remove the posts. Bird did not comply with this order.

The court also ordered Yelp to remove Bird’s review, even though Yelp was not a party to the case and was neither notified of the suit nor given an opportunity to contest the claims. Yelp unsuccessfully challenged the order in the Court of Appeal and has now appealed to the California Supreme Court. Yelp’s appeal raises First Amendment, due process, and § 230 concerns.

Section 230 (codified at 47 U.S.C. § 230) is an important and well-established statute that shields “interactive computer services” from liability for their users’ speech. It states: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” In other words, this statute means that online platforms like Twitter and Yelp are not responsible for content posted by their users.

Section 230 plays a crucial role in encouraging and protecting free speech on the Internet. Unlike more traditional forms of media like newspapers and books where content is curated, the sheer volume of speech uploaded to web services like blogs, social media sites, and review sites can be staggering—far beyond what can be practically monitored by the web hosts’ administrators and lawyers. Without § 230, Internet companies that rely on user-generated content would be exposed to crippling tort liability.

The Clinic’s brief, prepared with co-counsel Paul Levy of Public Citizen, describes how the lower court’s decision runs counter to well-established § 230 law and congressional intent. Worryingly, the decision establishes an obvious method for subjects of online speech to circumvent § 230’s protections:

- Sue the user, rather than host, for defamation, as § 230 clearly immunizes hosts like Yelp from being named a defendant.

- Obtain a default or stipulated judgment, since most users will not litigate the issue and many—like Ms. Bird—may not even be notified properly.

- Finally, use the judgment to force the host (here, Yelp) to remove the content, usually without giving it the opportunity to defend itself.

If allowed, these tactics can lead to a bizarre consequence: Internet companies that are not sued are more susceptible to liability than if they had been named a defendant. And Internet speech can be suppressed even if the plaintiff has no valid legal claim and the suit is brought solely to silence criticism or unpopular speech.

The brief explains the chilling effect the lower court’s decision would have on free speech online, and the impact on consumer awareness when review sites are forced to remove negative reviews in this way. The court’s decision is especially concerning given the rise of litigation strategies aimed at circumventing § 230. The brief details instances of “fake” litigation, in which imaginary users are named as defendants with the ultimate goal of forcing the host to remove the content in question. If judgments against users—especially default judgments against users who do not appear to defend themselves—can be translated into injunctions against hosts, the brief argues, § 230 will lose much of its potency. The Clinic’s brief urges the California Supreme Court to restore these § 230 protections in California and explains that a failure to do so would harm countless Internet companies that maintain their headquarters in the state.

News coverage of the Clinic’s brief can be found on Techdirt and the Public Citizen site.