Disclosing Prescription-Drug Prices in Advertisements — Legal and Public Health Issues

This article first appeared in The New England Journal of Medicine on November 14, 2018.

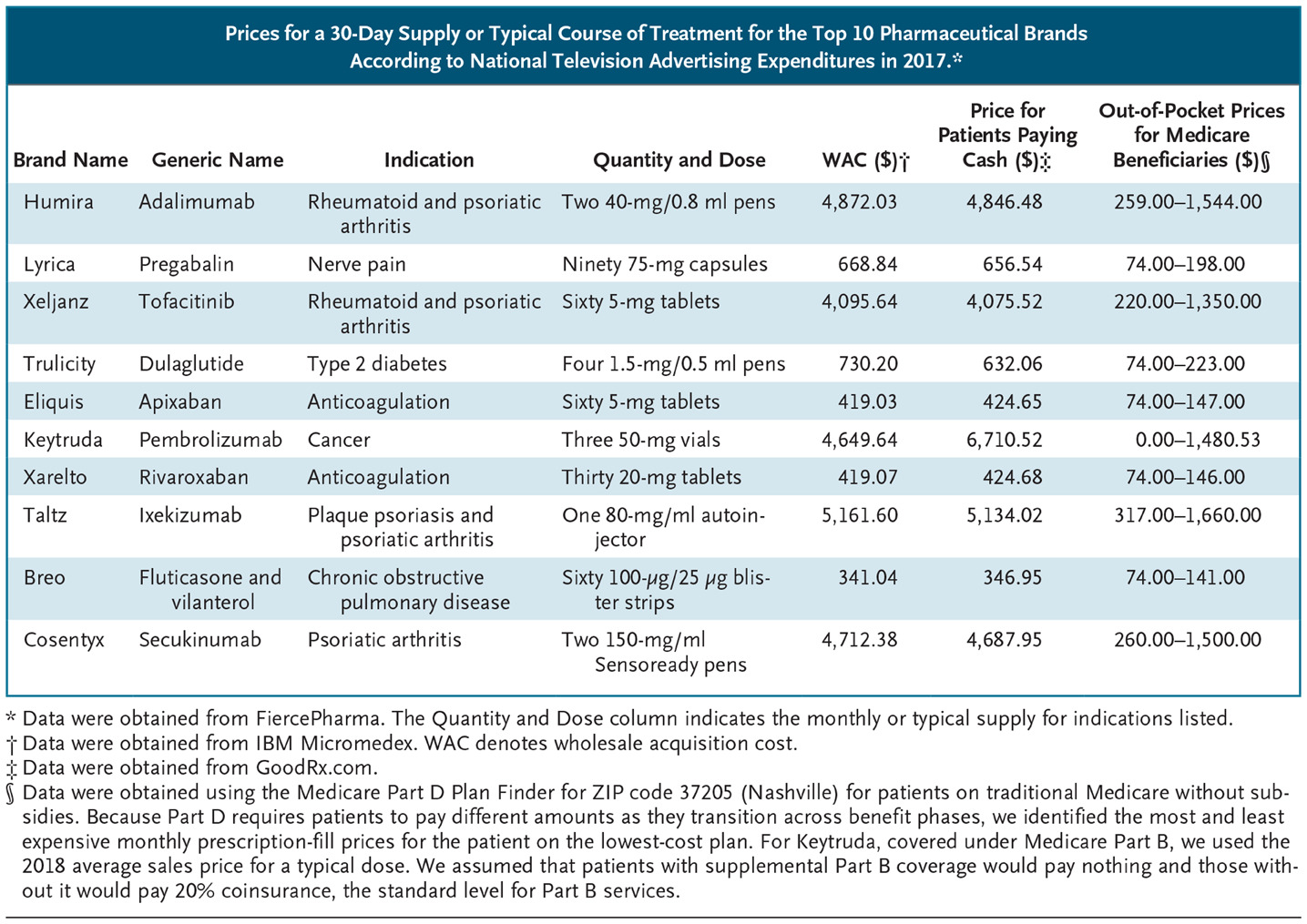

On October 15, 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed a rule requiring television advertisements for prescription drugs and biologic products to disclose the product’s price.1 The advertisements must state in legible text the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) for a 30-day supply or a typical course of treatment.

The rulemaking follows an unsuccessful effort in Congress to include a similar measure in the fiscal year 2019 appropriations bill. The idea enjoys broad public support — in a June 2018 poll, 76% of Americans favored requiring drug advertisements to include a statement about how much the drug costs2 — and it dovetails with moves to improve price transparency in other health care domains. But we think the proposed rule raises substantial public health and legal concerns.

Direct-to-consumer advertising is a natural target for regulation because it stimulates demand for expensive, brand-name drugs when there may be less-expensive generic drugs with similar efficacy and side-effect profiles already available, thus increasing the provision of cost-ineffective care.3 Yet such advertising could also stimulate undertreated patients to seek medical attention and effective therapies. For example, of the 14% of people in the same poll who reported speaking with their doctor about a specific medication after hearing or seeing an advertisement, the majority (55%) received a prescription for the advertised product, but respondents also said that providers recommended other prescription drugs (54%), over-the-counter drugs (41%), or lifestyle changes (54%).2

The CMS proposal reflects a desire to preserve the potential benefits of direct-to-consumer advertising while curbing its ill effects. However, a potential unintended consequence of price disclosure may be to dissuade patients from seeking care because of the perception that they cannot afford treatment. For example, Trulicity (dulaglutide), a widely advertised drug for type 2 diabetes, has a WAC (or list price) of $730 per month. Patients who could benefit from diabetes treatment may assume that they cannot afford it, when in fact insured patients’ costs for Trulicity may be much lower, and cheaper treatment options are available (metformin, for instance, costs $4 per month for patients who pay cash). Consequently, the proposal carries a risk of undercutting the main public health benefit of direct-to-consumer advertising: reducing rates of undertreatment.

That CMS chose the WAC as the figure that must be disclosed makes this risk especially acute. The WAC is a good estimate of what uninsured patients can expect to pay, and deductibles and coinsurance are commonly based on a drug’s WAC. However, this price is typically much higher than what insured patients pay. For example, 1 month of treatment with the anticoagulant Eliquis (apixaban) has a list price of $419, but out-of-pocket prices range from $10 for commercially insured patients using the manufacturer’s copayment card to $147 for Medicare beneficiaries in the Part D coverage gap (see table). Although CMS will require a statement noting, “If you have health insurance that covers drugs, your cost may be different,” this wording doesn’t communicate that costs to patients are probably much lower than the WAC.

(caption: Prices for a 30-Day Supply or Typical Course of Treatment for the Top 10 Pharmaceutical Brands According to National Television Advertising Expenditures in 2017.)

CMS used the WAC for several reasons. List prices matter for many patients, and having to disclose list prices creates incentives not to raise them. Moreover, it is impracticable to state what patients will actually pay because of variation in insurance design and coverage and the fact that rebates and discounts may not be determined when advertisements are made.

The rule’s use of list prices also has important legal implications. Disagreement about whether the WAC accurately represents a drug’s price could affect how courts assess the rule when constitutional challenges are inevitably filed.

Compelled disclosures in advertising impinge oncommercial speech rights protected by the First Amendment. However, courts apply a deferential standard of review known as the Zauderer standard in challenges to disclosures of “purely factual and uncontroversial” information relating to an advertiser’s products or services. Although CMS characterizes its requirement as falling squarely within Zauderer, there is a strong argument to the contrary.

Courts applying Zauderer have taken a narrow view of what constitutes a factual, uncontroversial disclosure. For example, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, reviewing a required warning that drinking sugary beverages contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay, held that because the disclosure did not state that overconsumption of beverages was the problem, it was “misleading and, in that sense, untrue.”4 Similarly, the WAC is not a factually accurate representation of what a drug costs for most patients, and the disclosure omits key information. This fact sets it apart from other fee disclosures that have survived legal challenges, such as the basis for calculating attorney fees and the amount of interest charged on loans.

If a compelled disclosure doesn’t qualify for Zauderer review, courts will apply heightened scrutiny. The most likely standard, Central Hudson, asks whether the government has a substantial interest that is directly and materially advanced by the speech restriction and whether the restriction is narrowly tailored to achieving that goal. Although the disclosure rule is narrowly tailored to the government’s substantial interest in reducing unreasonable expenditures by CMS programs, it probably doesn’t satisfy the material-advancement requirement. Courts have required the government to provide evidence that a required disclosure will effectively address the problem it targets. Graphic warning labels on cigarettes, for example, were struck down because the government’s regulatory-impact analysis suggested that they would reduce the U.S. smoking rate by only 0.088%.5 CMS offered no evidence of the likely effects of the proposed drug advertising price disclosure rule, noting only that it “may” improve consumer decision making but could also create confusion and that CMS could not quantify these effects.1

Three aspects of the rule undercut the government’s ability to argue that it will materially improve patient decision making and reduce drug spending. First, price information does little to inform consumer decisions if it inaccurately represents actual cost. Second, consumers can already obtain information on cash prices (which usually approximate list prices) online and their own cost from their insurer. CMS could argue that disclosing the WAC may advance the agency’s interest in reducing Medicare and Medicaid spending in another way: by shaming companies into lowering list prices. But since Medicare and Medicaid don’t pay list prices, this outcome seems implausible.

Third, the rule contains no meaningful enforcement mechanism — CMS plans only to list violators on its website — calling into question whether companies will comply. CMS believes that the main lever for inducing compliance will be private litigation: competitors can sue violators under the Lanham Act, which prohibits false or misleading representations in advertising or promotion. But such suits are not a robust means of enforcement. Omissions don’t qualify as falsities under the law unless they create an erroneous belief among consumers. What false belief arises from not stating a product’s price? Furthermore, the competitor must show that the falsity caused it to lose sales — a challenging task, since patients and prescribers may prefer one drug over another for various reasons.

Despite the problems associated with requiring disclosure of list prices, the sentiment behind the proposed rule — that patients should know how much drugs will cost before they fill their prescriptions — is sensible. The question is how best to achieve that outcome. Just before the CMS rule was announced, the main trade organization of the pharmaceutical industry, PhRMA, released its own guidelines for voluntary disclosure of the costs of advertised medicines. It proposes that advertisements direct patients to a website where the company provides information about list price as well as “average, estimated, or typical patient out-of-pocket costs.” This information is more useful than the WAC alone, but “typical” out-of-pocket costs don’t convey the variation in what patients pay.

We think that a better alternative would be making patient-specific cost information accessible at the point of prescribing. Some electronic health records systems now offer this feature, but it is unclear how often prescribers use it. We think that cost should become a routine part of prescribing discussions with patients, although time constraints could make it difficult to have such conversations. Providing salient cost information at the right time could help reduce drug spending while preserving patient choice, but we believe that direct-to-consumer advertising is the wrong vehicle.