The CRISPR Patent Decision: Your Six Takeaways

Summary

With the Broad Institute’s big win on Wednesday in its battle over key patents on the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology, everything is now crystal clear. Kidding!

The University of California seemed to be the loser, since the patent judges denied its effort to effectively block the Broad’s patents. But in a call with reporters, Paul Alivisatos, UC Berkeley’s vice chancellor for research, was upbeat that the ruling would allow UC’s patent claims to finally “move forward.” Berkeley biochemist Jennifer Doudna, whose pioneering CRISPR discoveries UC has been trying to patent, pronounced herself “delighted.” Alivisatos dodged a question about why, if UC found the decision so great, it had issued a statement saying it was “considering all of its options,” including an appeal.

…

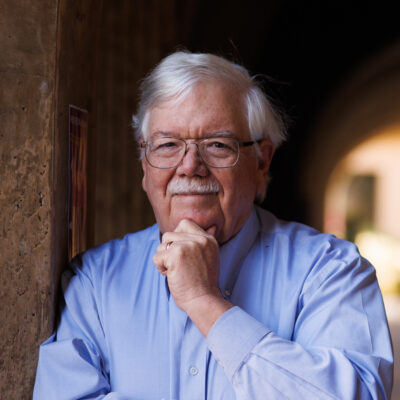

UC believes that any company that wants to use CRISPR to develop human therapies — we’re looking at you, Editas Medicine — will need to license not only the Broad’s patents on eukaryotic cells but also those UC expects to receive on all kinds of cells. “It looks to me as if someone wanting to use the Broad patent would also have to license the UC patent,” agreed law professor Hank Greely of Stanford University. “The UC patent (if granted) would be on any use; the Broad would be on use in eukaryotes. I think someone who wanted to do this in eukaryotes would need to have licenses to both.”

…

Yes. CRISPR-Cas9 is unlikely to be the last genome-editing technology ever discovered. In 2015, Zhang and his colleagues discovered a version called Cpf1, which they’ve now patented and licensed to Editas. “I continue to think the possibility of inventing around the [CRISPR] patents seems very likely,” said Stanford’s Greely. Bacteria “have certainly come up with other ways to reach the same end [of genome editing], ways that aren’t covered by UC’s or the Broad’s claims. That could make either of these patents ultimately of little importance … especially if the licensing conditions give people a strong incentive to come up with invent-arounds.” Science will march on.

Read More