Some Thoughts On The New Common Rule For Human Subjects Research

Summary

On January 18, 2017, in one of its last official acts, the outgoing Obama administration issued a final revised version of the Common Rule—the regulation that governs the treatment of human subjects in all federally funded research. This was the culmination of a process that began in 2011 when the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, or ANPRM, that envisioned major changes to the original 1991 Common Rule. Then, on September 8, 2015, HHS and 15 other federal departments and agencies released a Notice of Proposed Rule Making (NPRM) that proposed specific changes to the Common Rule and opened a 90-day public comment period.

The NPRM’s proposed changes would have greatly altered the rules for human subjects research, especially regarding biospecimens. Among the most controversial of its proposals was the expansion of the definition of regulated “human subjects research” to include research using anonymous or deidentified human biospecimens. This is a critical point because research that does not involve human subjects at all is not subject to the Common Rule’s requirements. The comments from industry, research universities, and scientific and professional organizations were highly critical of some of the proposed changes. There was an evident division between (critical) hard science and (supportive) social science (anthropologists, for example) commenters; bioethicists were generally critical, but there were opinions on both sides. In a previous GLR post, I reported on a withering critique of the biospecimen proposal from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which argued that “continuing expansion of federal regulations on research is diminishing the effectiveness of the U.S. research enterprise.”

…

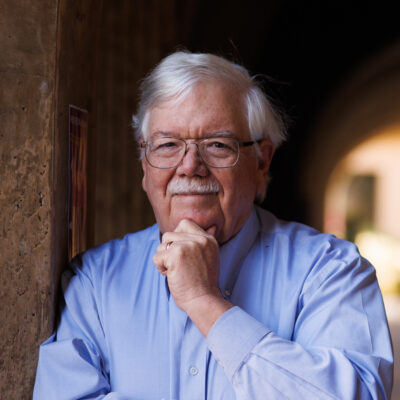

Several prominent bioethicists have criticized the failure to require informed consent for research on anonymous or deidentified human biospecimens. Hank Greely of Stanford has called it “a predictable result of the disparity in lobbying power” between the research and subject communities. Another critic is Rebecca Skloot, the author of the best-selling The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, about a poor African-American woman whose cells—without her knowledge or consent—gave rise to the HeLa cell line and, directly and indirectly, generated large amounts of money in which she and her descendants have never shared. A Lacks descendant has recently sued Johns Hopkins University in a belated effort to seek compensation. The suit faces many significant legal challenges—the biggest of which may be the statute of limitations.

Read More