Decriminalizing Poverty and Pigment: ArchCity Defenders, Alternative Spring Break, and the Long Road to Systemic Change

I spent the first twenty-two years of my life a short drive away from an epicenter of American racial oppression. But I had no idea what was happening in St. Louis County until a boy about my age was killed, laying bare my neighbor’s longstanding wounds.

As a brown kid from rural central Missouri, I was of course aware that racism existed, and even that it had real impacts on the daily lives of folks in my own community. I was blissfully unaware, however, of the systematic criminalization of poverty and pigment occurring just a hop and a skip down Interstate 70. From the outside, St. Louis appeared to be a thriving center of arts and culture, good hospitality, and communal pride. But simmering beneath the surface, outside the pages of the local newspapers and beyond the lenses of TV news, was one of the most deeply segregated metropolitan areas in the United States, home to perhaps the most problematic legal systems in the country.

Then, on August 9th, 2014, Michael Brown was shot. A teenager, three years younger than me, was gunned down on his walk home by a public servant sworn to protect him. His mother had to say goodbye to her child and his community collectively said “no more.” The simmering tensions burst forth.

The demand was simple: “Stop killing us.” St. Louis, the home of several of the most important civil rights lawsuits in our nation’s history, was again at the core of the movement for racial justice.

As my peers and I learned in our week volunteering with ArchCity Defenders, a legal services non-profit in St. Louis, Michael Brown’s death was but a heartbreaking chapter amid a much longer story. With a geography defined by racial animosity, white flight, neglect, and extreme wealth inequality, St. Louis offers a striking example of why race and poverty matter as much as ever in the United States today. As desegregation began in earnest after World War II and neighborhoods in the city of St. Louis began to diversify, white residents fled and established all-white communities. In a familiar pattern, federal, state, and local programs only fueled the exodus.

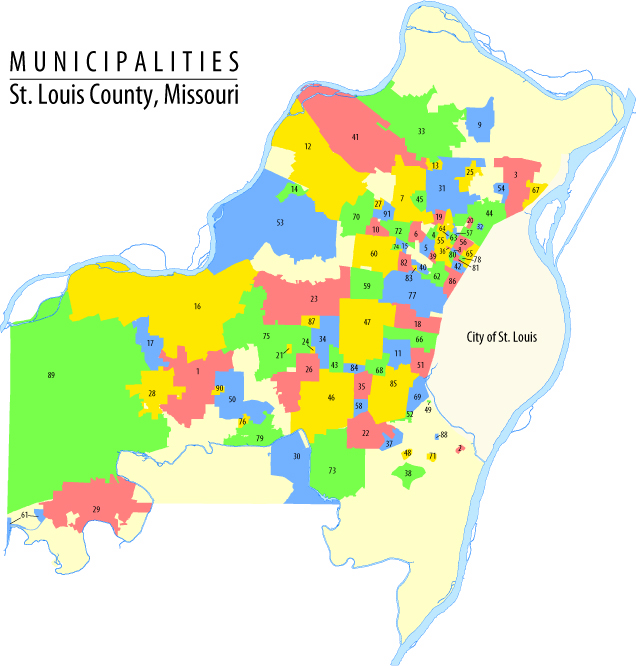

Because of a peculiar state law, each new subdivision was able – even encouraged – to incorporate as an independent municipality. The result was a slipshod patchwork of cities and towns across St. Louis County. Today, there are no fewer than ninety independent municipalities, including Ferguson, where Michael Brown lived and died, in the county. But as the dynamic of St. Louis city and county changed over time, many towns – home to as few as thirteen people – have struggled to remain relevant and financially stable.

One tool struggling cities discovered would keep their coffers filled was municipal court systems. In the years leading up to Michael Brown’s death, municipalities in St. Louis County used selective over-enforcement of city ordinances to collect huge proportions of their total revenues. Fines collected by municipal courts totaled more than $52 million in 2014 – that’s more than $50 for each person in St. Louis County. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch described the system as a “well-oiled money machine.”

And, as the U.S. Department of Justice concluded in its report on Ferguson, the city’s police department acted as a “collection agency” for its “constitutional deficient” municipal court system.

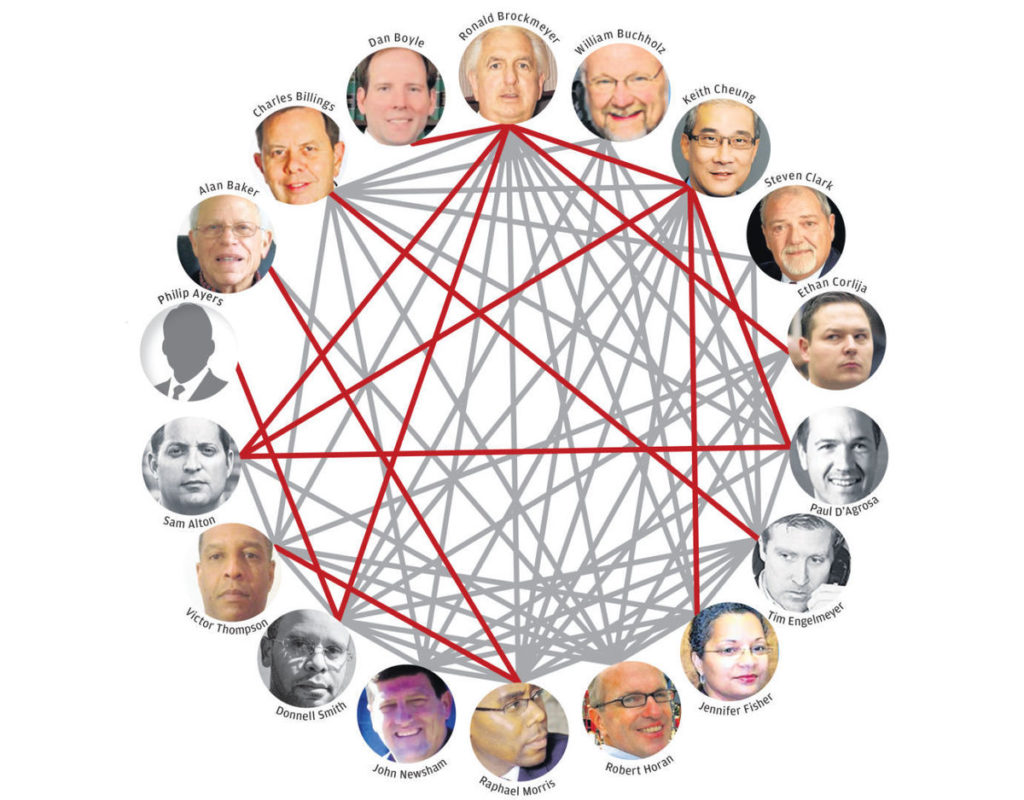

Enforcement, the DOJ pointed out, was not random. In cities like Ferguson, black residents were targeted disproportionately by police for stops, searches, tickets, and punitive action. Most often, residents were assessed significant fines for minor offenses. When many inevitably couldn’t afford to pay a ticket, municipalities exercised their almost criminally ill-defined and opaque powers under state law to “inflict” alleged offenders with jailtime in unconstitutional debtors’ prisons, among other civil rights violations. The picture becomes more troubling still when you consider who runs the municipal courts. As the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported, a startlingly small number of attorneys serve, depending on the day, as prosecutors, defense lawyers, and judges across the county. In other words, the same lawyer often serves as a prosecutor before a judge in one municipality whose case they will adjudicate as a judge in another municipality later the same week. Put simply, St. Louis County municipal courts present conflicts of interest.

So, when Michael Brown was shot, citizens of the St. Louis Area – especially poor and black ones – were already painfully aware that their government and police valued them only as a revenue source. While folks like me, watching from the far-flung suburbs or outstate, were caught off guard by the sudden conflagration, the black and brown residents of Ferguson and surrounding communities heard an especially salient call to action.

By the time national attention turned to St. Louis in 2014, ArchCity Defenders was already working to fix the broken system. Established in 2009, ArchCity started as prolific pro bono project focused on the legal needs of homeless St. Louisans and has turned into a thriving nonprofit with a staff of twenty-odd attorneys, social workers, and others. The organization applies a holistic approach: its mission recognizes that solving clients’ legal problems is only one piece of a more effective approach to care. As part of the conversation that arose in the wake of the tragedy in Ferguson, ArchCity added impact litigation to its repertoire. By leveraging partnerships with some of the nation’s foremost law firms, it has effectively integrated class action lawsuits and other strategies seamlessly with direct service delivery. Notable wins have included a multi-million dollar settlement with one municipality over unlawful conditions in its jails and acquittals of defendants charged in connection with protests in Ferguson. And the train keeps rolling forward: ArchCity recently sued the City of Ferguson and sixteen other municipalities in federal court for their “extortionist” policies and other violations.

During our Alternative Spring Break with ArchCity, I and seven other Stanford Law students conducted intake interviews, assisted with legal research, attended municipal courts as court-watchers, and interviewed homeless St. Louisans about their experiences in the city’s homeless shelters. In just one week, we’ve seen firsthand some the system’s shortcomings. In the tiny municipalities of Edmundson (pop. 837) and Hazelwood (pop. 19,297), we witnessed parades of black and brown defendants going before almost exclusively white judges and clerks. Most appeared without lawyers and pled guilty to the violations of which they were accused without anyone explaining the significance of a guilty plea. And these, we’re told, were “slow nights” at the courts.

It should be noted that the situation in St. Louis is egregious but far from unique. Cities and metropolitan areas across the country continue to criminalize poverty and blackness. During our week in St. Louis, we saw firsthand some of the challenges of systemic advocacy aimed at changing implicitly and systematically racist and classist institutions.

But there is reason to be hopeful. Through hard work and community-centered advocacy, institutions can be changed. After decades of criminalizing poverty and pigment, things are very slowly beginning to get better. Superfluous municipal courts have begun to consolidate in the face of accountability, the state legislature recently imposed caps on how much revenue municipalities can raise from fines, and political pressure has started to weigh heavily on those in positions of power.

ArchCity’s mission bears lessons for all of us. We – whether on the coasts or in the Midwest, in private practice, through pro bono work and philanthropy, working for a non-profit like ArchCity, or in government – must play our part in pushing for progress.

As a brown kid from a small town in central Missouri, a week with ArchCity was eye-opening. The problems we face are colossal and deeply entrenched. But there is a path forward and much to be done.

Let’s get to work.

For more information about St. Louis-area municipal courts’ myriad problems and how to get involved, see the ArchCity Defenders’ website and Municipal Courts White Paper.