Eviction and the Promise of Self-Help Technologies

“I have videos, Your Honor.” The tenant waves her phone in front of the judge. Her landlord rented her an apartment with a faulty air conditioner. It’s the end of the Arizona summer; temperatures rarely dip below triple digits. She works nights and can’t sleep days. Not in that place.

The tenant has been proactive, but it hasn’t helped. She notified the property manager, but he wasn’t able to fix the problem. She called local AC technicians, but they refused to work on her unit without the landlord’s approval. She sought approval from members of the property management team, but—with staff turnover and her own psychological turmoil, which she referred to in court with the parapraxis turn-oil—no one gave approval.

Eventually, the leak in the AC worsened, flooding the boxes she never unpacked. In the stagnant water, mold grew. This was the final straw for the tenant, who has allergies and corneal ulcers—for her, a mold infection could lead to blindness. So, she notified her landlord and stopped paying rent.

Today she is being evicted.

The judge stops and considers. There seems to be something here. He turns to her landlord’s lawyer and says, “I am really torn on this, counsel … . I am going to set this for a bench trial.”

The landlord’s lawyer stands up. “Your Honor, the statute clearly requires that she do certain things. She has not done those things. She is rent striking!” The judge interrupts him, asks clarifying questions. But the lawyer picks her case full with holes.

“Your Honor, she has full use of the apartment. If she is not there, she has no idea that repairs have been made. If she is there, then she is rent-striking and has not provided sufficient notice … . The statute is clear that if she does not do those things she is rent-striking. There is no offset. There’s not anything else. She owes this amount … . She still has claim against the property but not in this action.”

This argument proves fatal. The judge asks the tenant a few other questions—about notice and evidence, but with each question the tenant’s voice grows softer and softer. She is out of her depth, drowning. “Your Honor, I only slept an hour before this hearing … . I don’t understand. I have videos.”

A minute later the printer whirrs and it is over. The tenant walks back out into the familiar heat, judgment in hand, now owing $2,000. In all of this she has been desperately searching for someone to hear her, someone to respond to her life-threatening housing issue. Today’s hearing was just another disappointment. As the lawyer testified—and the judge reaffirmed—to assert her rights, she will now need to pay a lawyer or somehow figure out how to sue her landlord herself. All while homeless. The worst part is that Arizona law specifically allows tenants to bring these types of claims in actions for non-payment. She could have been heard.

“Eviction is where our adversarial system fails us. Lawyers and tenants face off in 90 percent of all eviction cases—with predictable results.”

— Daniel Bernal, JD ’19

I observed scenes like this in Arizona’s courts over and over this past summer. Thirteen thousand tenants are evicted this way in my hometown each year. Most don’t even bother showing up to court. And those who do are typically unable to frame their arguments in a way that makes a legal claim. Even if one exists. Eviction is where our adversarial system fails us. Lawyers and tenants face off in 90 percent of all eviction cases—with predictable results.

There are many different ways to approach this problem. The most obvious—the right to universal representation in housing court—perhaps holds the most promise. New York City has already legislated this right. But it is a right that is unlikely to grow here, in the Arizona heat, where last year only a handful of tenants were represented in their eviction hearings.

So, as we await a universal civil Gideon, I am studying the feasibility of another solution: self-help. With the help of my dissertation committee at the University of Arizona and several advisors at Stanford Law School, this past year I successfully applied for funding from the National Science Foundation. This was supplemented by Stanford’s Center on the Legal Profession and the dean’s office. In conjunction with the University of Arizona, the Arizona Bar Foundation, and Stanford’s Legal Design Lab, my team and I have created self-help materials for tenants facing eviction in Arizona. We ran a pop-up workshop at Stanford’s d.school during the spring quarter to design the materials to respond to specific psychological barriers that tenants face. We brought in evicted tenants to conduct usability tests. We chose three prototypes and ran a larger online test with Arizona tenants. Then we dug into landlord-tenant law and worked with housing attorneys from Southern Arizona Legal Aid and Community Legal Services to create the logic flows that would serve as the backbone for our website. Our designer, Carolyn Hampe, and our developer, Metin Eskili, created beautiful self-help materials. Finally, we translated everything into Spanish.

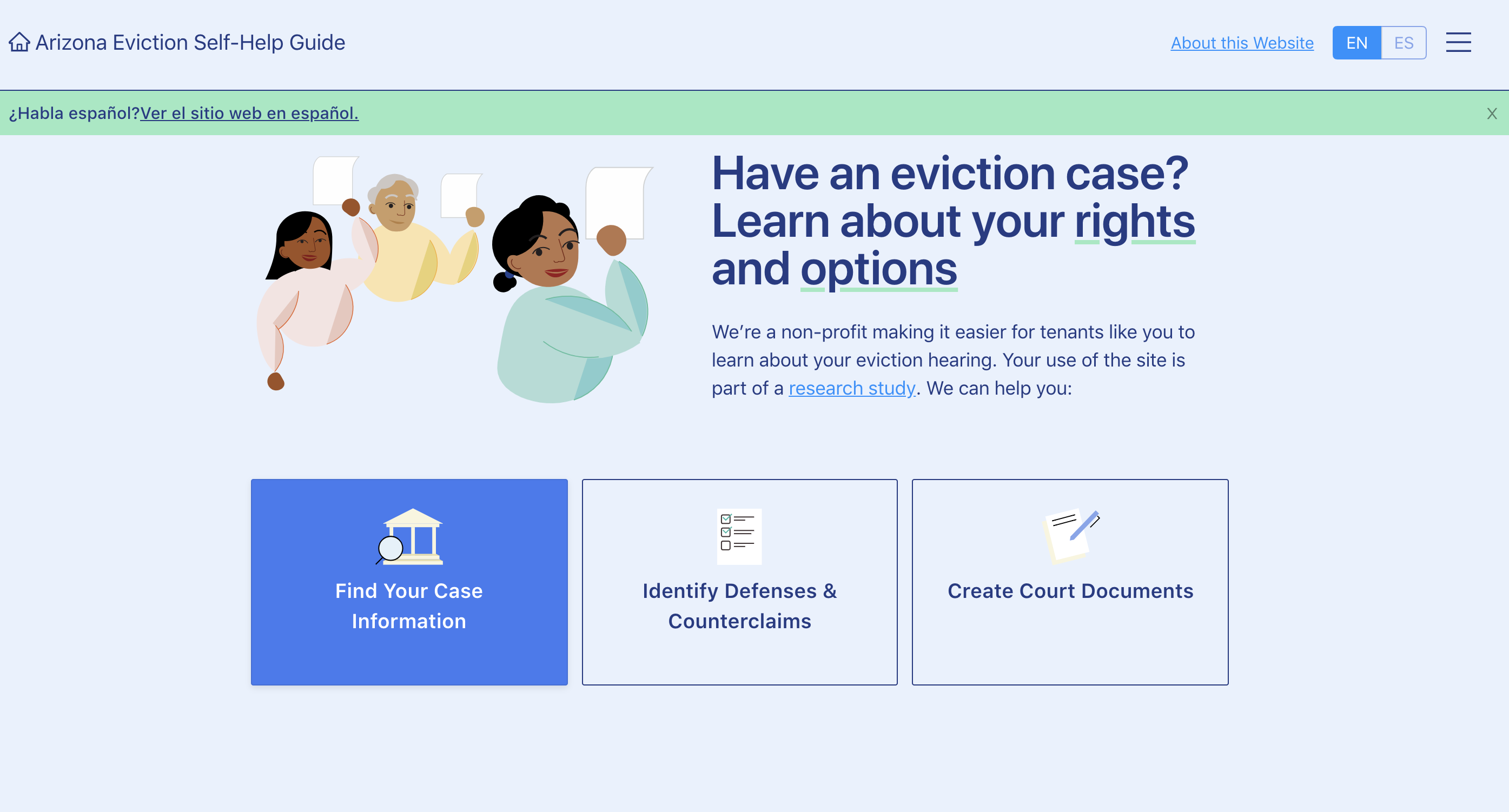

Next month, as a part of a randomized control study, a team of undergraduate interns at the University of Arizona and I will send out self-help mailers to tenants facing eviction in Arizona. These mailers are designed to help tenants know their options and rights and to overcome the major psychological and socio-economic barriers that keep them from court. Most importantly, these mailers contain a link to a mobile-friendly website that allows tenants to learn more information about their case, sign up for text-message reminders, identify available defenses and counterclaims, and automatically generate court documents. At the end of the four-month study, we’ll compare court attendance and case outcomes. In addition, we are analyzing court transcripts to determine whether these self-help materials impact tenant participation in court and will conduct a brief survey to determine whether these materials impact perceptions of procedural justice. Once the study is done, we’ll publish the results and release the materials to all Arizonans.

Whatever its promise, self-help will not create equity. Better information and auto-populated court documents cannot change the balance of power. Still, self-help may make a difference for many tenants. It may help tenants understand the consequences of doing nothing. It may help tenants translate their stories into a language that can be heard by our justice system. And maybe, just maybe, it may be enough to help tenants with broken air conditioners who gave their landlord sufficient notice to assert a valid counterclaim under A.R.S. § 33-1365. SL

Daniel Bernal is a JD student at Stanford Law School and is pursuing a PhD at the University of Arizona. At Stanford, he is a member of the Afghanistan Legal Education Project, the Youth and Education Law Project, and a student fellow at the Legal Design Lab. His research focuses on language access, self-help, and the role that information plays in cases of summary eviction.