Going Before O’Connor

Matthew J. Sanders ’02

“I’ve argued before Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.” This is the line I have used to deliberately mislead my colleagues, friends, and, yes, even my family members into thinking that fewer than five years out of law school I have argued in the U.S. Supreme Court. Of course I haven’t; the closest I’ve come is standing in the surprisingly narrow space between Nina Totenberg and Justice Stephen Breyer (BA ’59), while I was sworn in as a member of the Supreme Court bar. (In other words, not close at all, although I do feel supremely important when I bypass the public line on my way to the special people line to attend arguments at the Court.)

No, my line about Sandra Day O’Connor ’52 (BA ’50), while true, pertains to the different but no less thrilling experience of arguing before Justice O’Connor while she was sitting by designation on a panel in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, where I do most of my work as an appellate lawyer with the environment division at the U.S. Department of Justice. The case concerned a long-running dispute between snowmobilers and skiers who share a prime recreation area in the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, just south of Lake Tahoe, California. By the time the case reached my desk, the legal issues concerned whether the Ninth Circuit had jurisdiction to hear the appeal and, if it did, whether my client, the U.S. Forest Service, had taken reasonable steps to resolve the conflict and deal with the thorny legal status of a road that runs through the area.

The briefing was tough and Justice O’Connor was making me sweat before I even saw her, but fate had thrown me yet another twist. My opposing counsel was Deborah A. “Debbie” Sivas ’87, the director of the Stanford Environmental Law Clinic, under whom I had worked as a clinic student just four years earlier. And now, I had to litigate against her? Fortunately our good relationship was saved by 3L Paul Spitler, who stood between our zealous glares as he eloquently made his clients’ case. Stanford’s Margaret “Meg” Caldwell ’85, and a number of current students, also attended.

Stanford’s representation at the argument that day—on the bench and on both sides of the podium—reminded me of the law school’s excellence, of the stellar education I received in the environmental curriculum and clinic, and, most important, of the kind and collegial people who direct and participate in those programs. And did I mention that I argued before Justice O’Connor?

Matthew J. Sanders ‘02 practices in the Appellate Section of the Environment & Natural Resources Division of the U.S. Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. The views expressed in this article are Sanders’s personal views, not necessarily those of the Department of Justice.

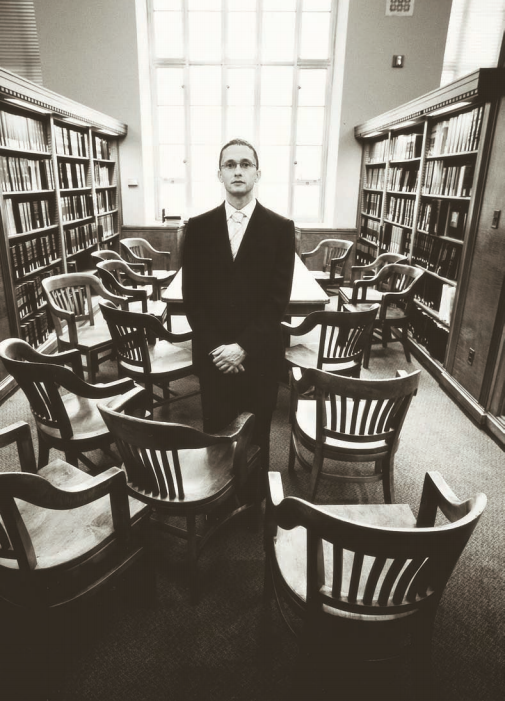

Paul Spitler ’07

We were gathered in the U.S. Court of Appeals building in San Francisco — a setting fit for a Hollywood courtroom drama with its ornate marble walls and floors, mosaic ceilings and murals. The courtroom was standing room only, so full that the hearing was being televised in the court’s cafeteria, which was also full. When the bailiff bellowed “All rise!” and announced our case, I took my last sip of water and stood. “Madam Justice, your honors, may it please the court. . .” Then, I launched into the first argument of my legal career, before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, with retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor ’52 (BA ’50) sitting on the bench.

It took this case six years to reach the Ninth Circuit, wending its way from a small swath of national forest land south of Lake Tahoe where snowmobilers were competing with skiers for space. In 2000, the Stanford Environmental Law Clinic filed suit on behalf of the skiers, known as Friends of Hope Valley, against the U.S. Forest Service, alleging that the forest service management plan for the area was unlawful in allowing snowmobile use. After years of failed settlement discussions and an unsatisfactory district court decision, the case landed in the Ninth Circuit in fall 2006. Under special rules, the Ninth Circuit allows students to receive certification to argue cases. As a thirdyear student in the Environmental Law Clinic, I had helped to develop the appellate briefs and was selected to argue the case.

I had, of course, never argued a case before any court, much less the Ninth Circuit. And if that were not enough, soon before the hearing, an excited court clerk called to inform us that retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor would be sitting on the threejudge panel that would hear our case.

On the Supreme Court, Justice O’Connor was renowned for pushing counsel to apply their argument to hypothetical scenarios she created. Another judge on our case, Judge Susan P. Graber, was known for asking extremely detailed questions about the administrative record for the case. The last judge, Judge Richard G. Tallman, was not known as a tough questioner but was considered conservative on environmental suits.

I had to be ready for it all. With the assistance of Environmental Law Clinic Director Debbie Sivas ’87, I tore into preparations—setting out a lengthy list of potential questions—which my wife quizzed me on during breakfast. And lunch. And dinner.

Mere seconds into my opening statement, Judge Tallman interrupted me. “Do we even have jurisdiction over this case?” he asked. I coolly responded as if I had heard the question a thousand times before. It was the first question on my list.

A month after the argument, the court dismissed our appeal. Because the management plan had been sent back to the forest service for revision, the court concluded that our appeal was premature.

The result was, of course, disappointing, but it took nothing away from the experience. I learned an immense amount about how to think through a case and how to prepare and present an argument. Those valuable skills are difficult, if not impossible, to learn in a classroom and will serve me well in my future career.

Paul Spitler plans to join Shute, Mihaly & Weinberger after graduation where he hopes to continue practicing environmental and land use law.