Immigrants’ Rights Clinic

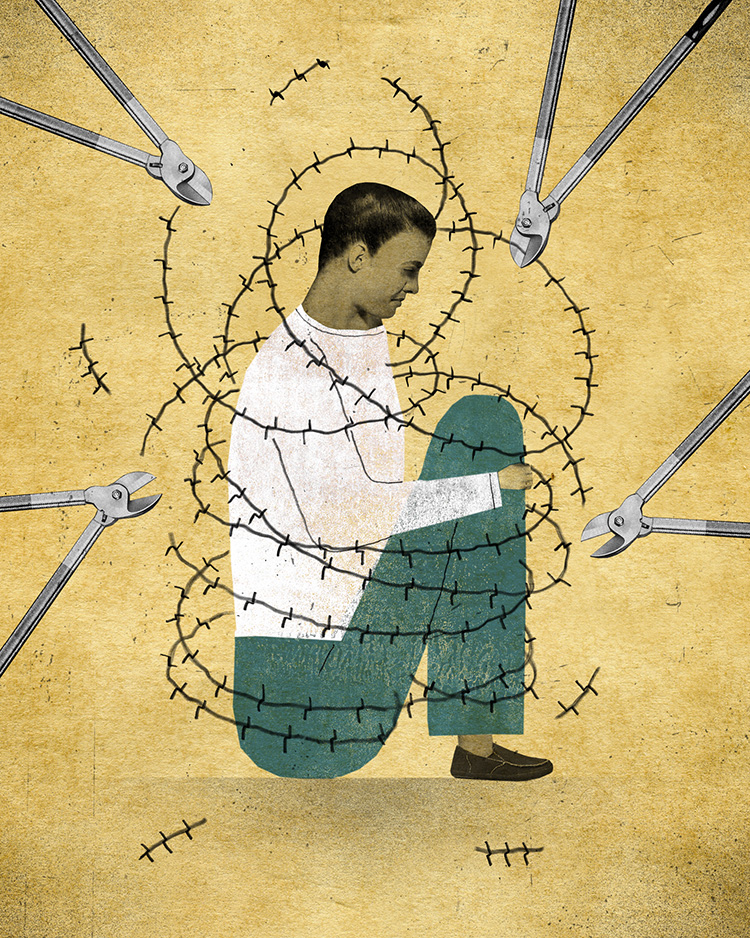

The client was facing the unimaginable. A lawful permanent resident for nearly 30 years, he regularly crossed the border from the United States to take trips abroad and back again without incident. But this time was different: Border agents stopped him based on a decade-old minor criminal infraction and threw him into deportation proceedings.

That’s when the Immigrants’ Rights Clinic (IRC) got involved. “Our client had signed plea agreements on the original charges and was told they would ‘disappear’,” explains Mishi Jain, JD ’21. “But that only applied in the criminal system and not in the immigration system.”

Looking for a creative solution led Jain and her clinic partner to the discovery of a new California post-conviction relief law that seemed tailor-made for the client’s situation, allowing for criminal records for immigration purposes to be set aside where plea bargains like his were involved.

“We worked with the public defender, who contacted the district attorney,” Jain says. “Then we prepared a massive packet supporting application of the new law.”

And to the relief of the client and the clinic, the criminal court vacated his record of everything that had immigration consequences. A return trip to immigration court resulted in dismissal of the deportation proceedings.

Client-centered direct representation is one of the hallmarks of IRC, complemented by policy projects, including impact litigation. “A public interest lawyer needs more than one tool in her toolkit,” says Jayashri Srikantiah, associate dean of clinical education and director of the Mills Legal Clinic. Srikantiah innovated a dual-advocacy model, in which each student has the opportunity both to represent an individual immigrant facing deportation—whether in immigration court, appellate administrative proceedings, or federal court—and to participate in impact litigation and advocacy.

Maria Elizabeth Trujillo, JD ’21, engaged deeply with impact litigation and advocacy while working with detainees held at a Northern California prison to improve access to lawyers for individuals that the government has placed in the Institutional Hearing Program (IHP). That program allows immigration judges to conduct fast-paced removal hearings while immigrants are still serving time in federal or state correctional facilities.

“There was no privacy for client-lawyer phone calls, the sound from video conferences could be heard from hallways where guards stood, and the mail was being opened, even if it was marked ‘legal,’ ” Trujillo explains.

Trujillo’s IRC team was tasked with providing information to detainees who wished to file grievances and to gather additional information about detainees’ experience with the IHP. “It’s a big decision to file a grievance while in prison,” she says. “If they file a grievance, it’s going to affect their everyday life. We focused on clearly informing them about the grievance process and—most importantly—to their experiences and their concerns.”

Beyond its work assisting detainees facing the IHP, the IRC has long worked to assist immigrants detained by the federal authorities pending their removal proceedings through impact litigation and direct representation. COVID-19 has created another layer of complexity in an immigration detention system that is already plagued by difficult challenges. “We recently obtained release for a client who was held at a detention facility with no social distancing, no sanitation, no masks—and a small child,” according to Lisa Weissman-Ward, IRC clinical supervising attorney and lecturer in law.

While the COVID pandemic has affected IRC’s clients in innumerable ways, it has also created opportunities for students to think creatively about how to flexibly represent clients in challenging circumstances. In May, for example, an IRC student appeared remotely before the Immigration Court. The judge, client, student, and supervising attorney all called in telephonically from different locations. Weissman-Ward observed, “While no one would wish this pandemic on even our worst enemies, we are leaning into the work with more energy than ever and finding ways to turn the new challenges into opportunities for unique lawyering experiences that students might never experience again.”

Shanti Tharayil, a litigation and advocacy fellow with IRC, likewise has faced the impact of COVID in litigation. She has worked with Srikantiah and clinic students on class action litigation to increase access to legal representation for immigrants detained in a Southern California facility. The effort, co-counseled with the ACLU of Southern California and the Sidley Austin law firm, resulted in one of the first post-COVID injunctions in the country to ensure such access.

Tharayil says that the experience of working at IRC is incomparable. “Jayashri and Lisa choose cases that are not only legally and factually complex but are also perfect vehicles for teaching lawyering skills on the job. No one gets this experience in practice.”

Nayna Gupta, JD ’13, would no doubt concur. Now associate director of policy at the National Immigrant Justice Center, where she spends her time advocating on behalf of immigrant communities on the Hill, Gupta credits IRC with not only launching her career but also supporting her at critical junctures along the way.

“The clinic’s high standards for work product and dedication to clients were formative experiences. Equally important, however, has been Jayashri’s guidance since graduation. She always makes time to advise former clinic students and guide them to the path that fits their strengths and passions. Having a mentor who is dedicated to legal academic excellence and pedagogy, and how those are related to real life, has been invaluable.” SL