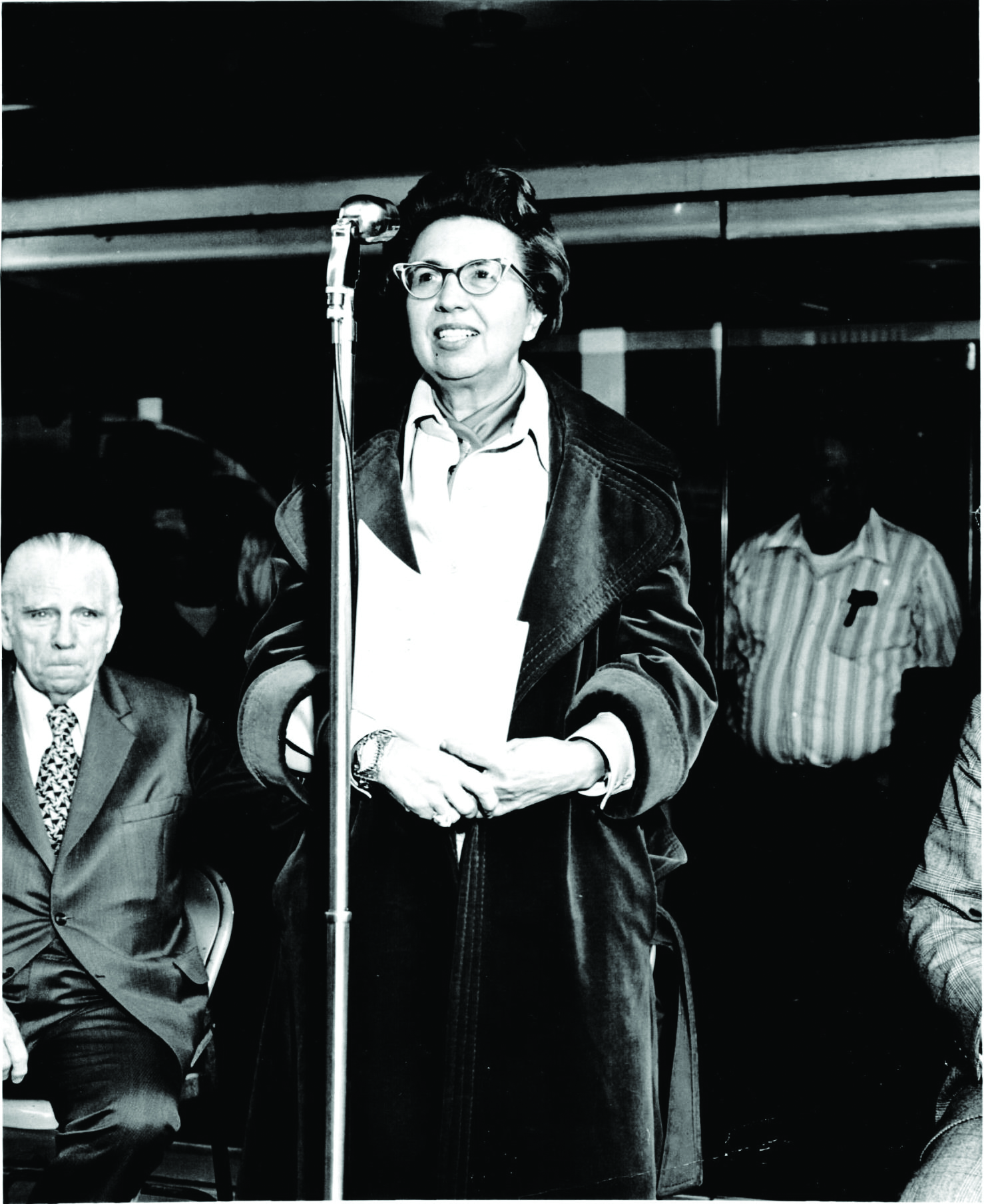

Remembering Miriam E. Wolff: July 24, 1916 – August 27, 2018

Miriam E. Wolff, Stanford Law School Class of 1940 (BA ’37), died at the age of 102 this past summer. I was fortunate to have known her for my entire life and to have benefited from her influence and inspiration. Miriam was a trailblazing woman lawyer and judge in an era when the legal profession was male-dominated. Throughout her career it was always important to her to act as a mentor to younger women and to open opportunities for them.

She and my mother met during the 1930s as undergraduates at Stanford and became lifelong friends. They had much in common: They both had keen senses of humor, loved reading, excelled at bridge, and were avid Stanford sports fans.

Miriam wanted to be a lawyer from her grammar school days and entered Stanford Law School in 1936 as one of a handful of women. While she was there, some faculty members admonished her that she was taking up a man’s place. Upon graduation, she encountered difficulty in finding a job in a law firm, very few of which were willing to hire a woman lawyer in that era. Instead, she took a civil service examination and went to work as a deputy attorney general for the State of California, where she thrived in a relatively nondiscriminatory environment.

Miriam served in that role for 23 years, handling a wide range of cases including business, administrative, and environmental law matters, with a special emphasis on maritime and admiralty law. As a deputy AG she represented the Port of San Francisco on behalf of the state, and when authority over the port was transferred from the state to the City and County of San Francisco in 1968, she was selected to be the port’s chief counsel. Two years later in 1970, with her elevation to port director she became the first female port director in the world.

Although she worked in San Francisco, Miriam lived in Menlo Park and later built a house with a swimming pool in the middle of an apricot orchard in Los Altos Hills, where she lived for more than 60 years. She commuted daily to San Francisco by train, playing bridge en route with other lawyers and judges. If she needed to work in the evening or had a social engagement in the city, she knew she could spend the night at our house in San Francisco. During football season, my parents and my younger sister and I would go to Stanford home games with Miriam, often spending the weekend at her house and swimming in her pool.

During my early years, Miriam was both a family friend and a role model of an independent and self-sufficient professional woman in an era when there were very few. Her dinner table discussions of legal issues whetted my interest in the law. She nurtured that interest when I was an undergraduate at Stanford and arranged for me to meet with former acting Stanford Law School Dean Samuel Thurman in the spring of my senior year, 1961. His encouragement and Miriam’s persuasion convinced me to take the LSAT and apply to the law school. Her support during my years at the law school as one of a small minority of women students was vitally important to my ability to persevere and succeed. She truly made a difference in launching my career.

I am one of many women who owe Miriam a great deal for her support. When Miriam became the director of the Port of San Francisco, she took a leading role in opposing gender and race discrimination by organizations leasing property from the port. The World Trade Club was located in the Ferry Building one floor above Miriam’s office. It did not admit women to membership or allow them to eat luncheon in its dining room. Miriam successfully persuaded the club to alter its rules and became one of its first women members. She also made clear to other restaurants on port property that they could no longer refuse to serve customers on racial grounds.

Miriam stepped down as port director after five years. She was appointed the first woman judge on the Municipal Court of Santa Clara County by then Governor Ronald Reagan. One of her first acts as judge was to allow women to wear pants suits in her courtroom, a controversial issue at the time. After a decade on the bench, she retired in 1986 at age 70 and for 10 years thereafter continued to hear cases by assignment by the court.

During her career Miriam was active in professional organizations supporting women, including Zonta International, a professional and business women’s service club, and the National Association of Women Judges. She also cherished her connections with Stanford Law School, chairing its Board of Visitors during the building of the current law school and regularly attending reunion weekends up until at least 2014, 74 years after her graduation. After retirement Miriam also developed a passionate interest in the arts, became a volunteer at Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center, and helped to arrange and lead a number of art tours for the center.

I will miss Miriam’s wisdom and guidance, but she leaves us all an important legacy of helping to open the legal profession to women. SL