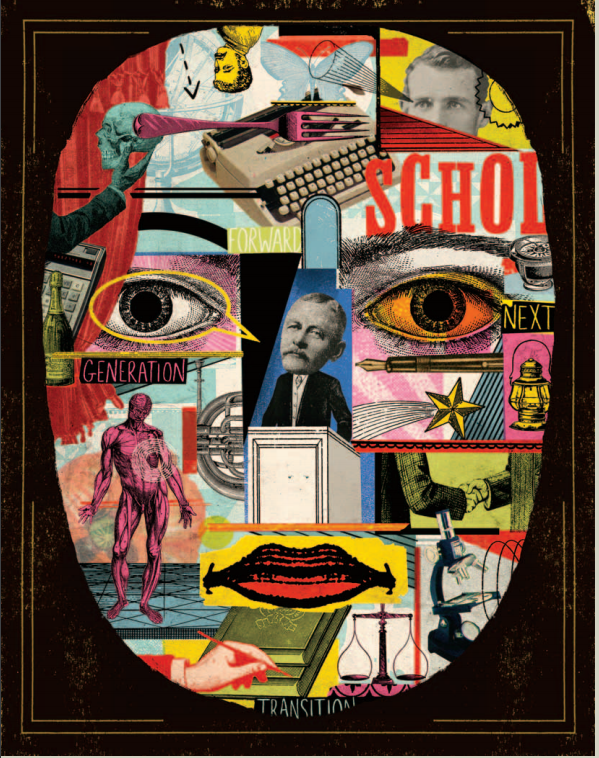

The Next Generation: Preparing the Next Generation of Legal Scholars

The fictional Professor Kingsfield of The Paper Chase fame would probably not be hired to Harvard Law School today. To become a contracts professor at Harvard, Kingsfield was likely near the top of his class, held a prestigious position on the law review and an equally sought-after clerkship. He may have briefly practiced, and was tenured shortly thereafter, while writing mostly doctrinal work. To be hired at Stanford, Harvard, or any top-tier law school today, Kingsfield would need a whole different set of credentials. Grades and clerkships matter less than publications and a well-developed research agenda. As a result, Stanford Law and schools across the nation are grappling with how best to prepare students interested in academic careers for this new environment.

Teaching was the primary job of faculty members in law schools a generation ago. “Law faculties across the nation were full of really smart law students, but not necessarily great scholars,” says Larry Kramer, Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Dean. Today new hires no longer get the benefit of the doubt; their scholarly potential must be proved from the outset. “This new focus means that the classic big three—law review experience, grades, and clerkships—have lost importance,” says Lawrence M. Friedman, Marion Rice Kirkwood Professor of Law.

The driving force of change in the legal academy over the past generation has been scholarship, both at entry level and at time of tenure. “Until about 25 years ago, scholarship played a relatively minor role in the legal academy and tended to take one narrow, doctrinal form. The typical law professor wrote one tenure piece and then never wrote anything again other than casebooks or hornbooks,” says Barbara H. Fried, William W. and Gertrude H. Saunders Professor of Law. That began to change in the 1970s with the birth of the law and economics and critical legal studies movements on campuses across the country. “These movements were defined by the fact that students who came out of the 1960s were much more sophisticated in what they sought to do as scholars,” says Kramer. Although standards differ widely from department to department, at time of tenure today the quantity and quality of writing expected of law professors is as rigorous as in any part of the university.

But what explains this shift? University administration is part of the story. According to Friedman, “Universities have been putting more and more pressure on law schools to apply the same scholarly standards as other departments in universities. This means placing a greater emphasis on research and publications.” Hence the proliferation of law professors with doctorates in other fields—these scholars already have proved capable of producing a body of excellent work. The increasingly interdisciplinary nature of the legal academy has also led to new opportunities in the field.

“What counts as legal scholarship has broadened significantly over the past twenty years,” says Fried. As the definition of legal scholarship has expanded, so too has the attraction of law teaching for students and scholars who are interested in more than doctrinal work. Today, legal academics are not only blogging and writing newspaper op-eds, but are also researching the legal aspects of a greater variety of fields than ever before. A few examples of broad scholarship by faculty at Stanford Law include Richard Thompson Ford’s (BA ’88) book The Race Card: How Bluffing About Bias Makes Race Relations Worse, and Alison D. Morantz’s award-winning empirical study of workers’ compensation claims.

That is not to say that a PhD is now required to enter legal academia. But, “just plain being smart and having good lawyerly skills aren’t enough to get you a teaching gig anymore. You need to have produced at least some good scholarship, and have something else,” says Kramer. “That something else might be training in another discipline, or it might be experience and thoughtfulness about how the law operates in some area. But something.”

Responding to the change in scholarly expectations, Stanford Law offers a wide variety of programs and initiatives designed to make its students competitive on the law teaching market. The law school also offers substantive fellowships that give law graduates the chance to gain teaching experience and focus on research and writing in their chosen field. These fellowships are the equivalent, in many ways, of “post-docs” in other fields, but this is such a new idea in law schools that even current fellows have been struck by it. “When I got the corporate governance fellowship three years ago, it was not yet established that the position was a path to teaching. Now, it’s expected that you’ll go on the market,” says Brian JM Quinn ’03 (MLS ’01), the corporate governance and practice teaching fellow at Stanford Law until July, who joined Boston College Law School’s faculty as assistant professor in fall 2008.

In addition to the legal research and writing fellowship program, Stanford Law offers specialized fellowships in a range of fields including clinical education, corporate governance, the Stanford Program in International Legal Studies (SPILS), law and the biosciences, Internet and society, constitutional law, environmental law, criminal justice, and more. And new fellowships are being added almost yearly. In total, Stanford Law has more than quadrupled the number of fellows over the past five years from eight to approximately 36 in the fall 2008 term.

“The fellowship program at SLS has been a fabulous experience,” says Laura K. Donohue ’07, fellow at the Stanford Constitutional Law Center from 2007–2008, who now clerks for Judge Noonan on the Ninth Circuit. “When I started my fellowship there were 18 fellows, which was already the largest number at any top law school. But we’ve since more than doubled even that number.”

But it’s not just a numbers game that is driving growth. “The development of these fellowships is critical to give potential teachers and scholars a chance to develop before hazarding the market,” says Kramer. “Fellowships help improve the overall quality of legal teaching and scholarship and thus greatly benefit legal education.”

“The faculty has been extremely supportive and I’ve learned a huge amount. I’ve finished a book and organized several conferences with Professor Kathleen Sullivan,” says Donohue. Donohue’s most recent conference addressed the constitutional issues of quarantine in a biological weapons attack that featured speakers from the White House, U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Northern Command, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “And I got to do that just because Kathleen asked what would I like to do,” says Donohue.

BEYOND FELLOWSHIP PROGRAMS, Stanford Law offers numerous formal and informal joint degrees. Over the past two years, Stanford Law has established 20 joint degree programs with different departments, schools, and interdisciplinary programs at Stanford that allow students to get a master’s degree or PhD concurrently with their JD. This has never been more important given how quickly legal education is changing. “Universities have traditionally been structured as a set of adjacent boxes: humanities, business, etc.,” says Kramer. “Now, the boxes are beginning to dissolve. What we’re seeing is a change in higher education itself. Instead of scholars working alone on articles and books as goals unto themselves, scholarship is increasingly defined in terms of projects that require scholars to work collaboratively in teams with students, academics, and policymakers. Books and articles are becoming by-products rather than end products of an ongoing effort to address and solve a larger project or problem in the real world.”

As a result of these entrepreneurial efforts, Stanford Law is doing increasingly well in placing its graduates and fellows in this highly competitive environment. In the past two years alone, 22 Stanford Law graduates were appointed to tenure-track teaching positions, which represents 6 to 7 percent of each graduating class. The 22 people who secured jobs represents 70 percent of the total number of Stanford JDs who went on the market in those two years—an astonishingly high success rate.

And fellows have organized to support their success on the job market. Two years ago, for example, the fellows began a series of workshops on the law faculty hiring process, along with strategies for effective teaching and writing. “The year before we started this, six fellows got jobs at second-tier law schools and one at a tierthree school. In this last cycle, every single fellow who went on the market got a job at a top-tier law school,” says Donohue.

Stanford Law has made such a push to assist legal scholars for several reasons, according to Fried. “We have an obligation to all of our students to do the best job we can to train them for the legal careers they want,” she says. “Law professors also have a disproportionate amount of influence in shaping the next generation of lawyers and policymakers, and in shaping policy itself. And as interdisciplinary work becomes more and more important in law, world-class universities like Stanford have a critical role to play in training legal academics as well as lawyers.”

Today, more students than ever are choosing a career in legal academia. And the hiring process sponsored by the Association of American Law Schools (AALS) has become the gauntlet through which these aspiring law teachers must pass. The process involves submission of a summary of publications, research interests, and references, which hiring law schools then examine. Those who are picked for interviews attend the annual AALS conference, known not so fondly as “the meat market,” and follow up this process with interviews at interested schools.

Why the increase in applications to teach law? Theories range widely from market conditions to disenchantment with firm life. “The academic life provides something that is hard to replicate elsewhere— the opportunity to decide for yourself what you think is important and true and to put that at the center of your work as a teacher, scholar, and citizen,” says Fried. Quinn adds, “I love to teach, research, and think. From that standpoint, teaching law is a perfect job.”

Of course, the professorial lifestyle is certainly not for everyone. “You have to flourish in a highly unstructured environment,” according to Friedman.

DESPITE THE DRAWBACKS, LAW teaching is still compelling to many students and attorneys. Given the change in legal academia, close student-faculty contact has never been more important to finding a position. “In short, what has always mattered most to graduate students in other disciplines has become increasingly important in law: the quality of the faculty and breadth of course offerings in areas of most interest to the student, opportunities for writing, and the relevant faculty members’ track records as academic mentors,” says Fried.

“The law school faculty, especially Mike Klausner and Ron Gilson, have been tremendously helpful to me during this process,” says Quinn. “Not just in the classroom, but also mentoring, giving advice, going over paper topics, reading drafts, and generally making sure that I was headed in the right direction. I wouldn’t have been successful without their support.”

Scott James Shackelford ’09 is a PhD candidate in international relations at the University of Cambridge, and a co-founder of SLS Academy, a student organization that supports those interested in academic careers. For more information about SLS Academy and the fellowship program at Stanford Law, go to www.law.stanford.edu