The Rule of Law: Herman Phleger Lecture

In Robert Bolt’s play, A Man for All Seasons, Sir Thomas More’s son-in-law William Roper urges him to arrest the man whose deceit will ultimately result in More’s downfall. When More responds that the man has broken no law, Roper accuses him of “sophistication.”

“No, sheer simplicity,” More answers. “I know what’s legal and I’ll stick to what’s legal. If it were the Devil himself I’d let him go until he broke the law.” When Roper asserts that he would cut down every law in England to get after the Devil, More responds: “And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned round on you-where would you hide, the laws all being flat? This country’s planted thick with laws from coast to coast; and if you cut them down, do you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? I’d give the Devil the benefit of the law for my own safety’s sake.”

Richard E. Lang

Professor of Law and Dean

After the attempted coup last August, there was widespread concern and anger that its sympathizers were still at large; President Gorhachev was urged to ferret them out and arrest them. He responded: “I do not think that after all of this we should do any witch-hunting. We must act within our democratic framework and the framework of our glasnost and on the basis of our laws. Political revenge would ultimately mean defeat for the forces of democracy; it would mean carrying out the intentions of the plotters. There has to be rule of law.”

I shall not strain the analogy between the Lord Chancellor of England and the recent President of the U.S.S.R.-two enormously complex individuals, separated by almost four centuries and vastly different cultures. Nonetheless, the comparisons go beyond each man’s refusal to deal lawlessly with those who themselves subverted the law.

Both King Henry VIII and the coup plotters last August desperately sought the cloak of legality. Henry (you may recall) was frustrated by More’s refusal to acknowledge the lawfulness of his marriage to Anne Boleyn. More was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he was threatened, bullied, and tormented. Yet he did not yield. The playwright describes him as “a man with an adamantine sense of his own self. He knew where he began and left off, what area of himself he could yield to the encroachments of his enemies, and what to the encroachments of those he loved. Since he was a clever man and a great lawyer, he was able to retire from those areas in wonderfully good order; but at length he was asked to retreat from that final area where he located his self. And there, this supple, humorous, unassuming, and sophisticated person set like metal, was overtaken by an absolutely primitive rigor, and could no more be budged than a cliff.”

When the plotters pounded on President Gorbachev’s door in his home in the Crimea, he told his family: “If the worst happens, I will stand for my position and will not yield to blackmail.” The plotters pushed into his office and demanded that he declare a state of emergency. He refused. Then they demanded that he sign over the presidential powers. Again he refused, charging that “You and those who sent you are reckless adventurers.” Finally, they demanded that he resign; and he responded: “You’ll never live that long.” Instead, he offered a legal alternative: The Soviet Parliament could address the emergency in democratic debate. The plotters were deaf to this suggestion. They tightened the guard around his home and left without responding.

What is so striking about the plotters’ demands on the President is that even in the midst of their utterly lawless action, they felt it essential to clothe themselves in the trappings of constitutionalism. This in itself was the product of the transformation President Gorbachev had wrought in Soviet society. In any event, the plotters were not prepared for a man whose commitment to the law, to his nation, and to his own integrity, would not allow him to yield to their threats.

Years before he became Chancellor, Thomas More wrote a biting critique of fifteenth-century England that also set out his vision of the good society. In More’s Utopia, property was owned in common-for moral rather than economic ends. He saw human greed and pride as the fundamental barriers to a just and productive society and to a personally fulfilling life.

It was, I believe, a vision of this sort that underlay President Gorbachev’s commitment to socialism and his program of glasnost. And if his most ambitious hopes for his country have not yet been realized, he nonetheless gave its peoples the great freedom of democracy: the freedom to create the society of their own choice. This freedom carries a heavy responsibility, which no nation, our own included, has consistently lived up to.

Harnessing self-interest for the common good is the never-finished task of every society. Surely, it is a crucial task for the new societies that are struggling to emerge in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. And the rule of law-in the personal security it offers its citizens, and the stability it affords property rights-is an indispensable element of that enterprise. (If the tragic events following the verdict in the Rodney King beating case have cast a shadow over the rule of law in our own land, we should treat those events as an urgent call to assure that the law rests on strong foundations of justice.)

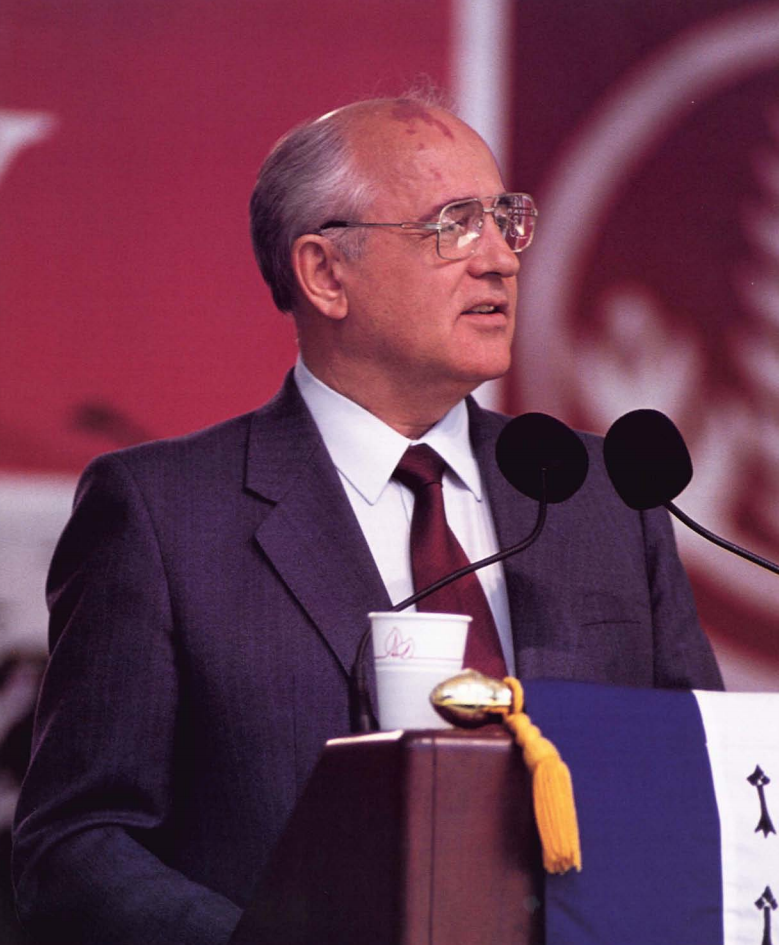

It is a great honor to have with us at Stanford University, as the Herman Phleger Visiting Professor of Law, the man who has made the democratic rule of law and the aspirations for justice a real possibility for hundreds of millions of people. Ladies and gentlemen, let me introduce my newest Stanford Law School colleague-a man who received his own law degree from Moscow State University-Professor Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev.

-Paul Brest, Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Dean

Delivered May 9 at the Frost Amphitheater as the introduction to the 1992 Herman Phleger Lecture. (Some of the Bolt passages depart slightly from the original.)

The Rule of Law

Friends! I am here among you for the second time at your world-famous university, whose achievements and whose graduates play such a prominent role in scientific research and in the humanities. I was happy to accept your invitation to speak before you here today.

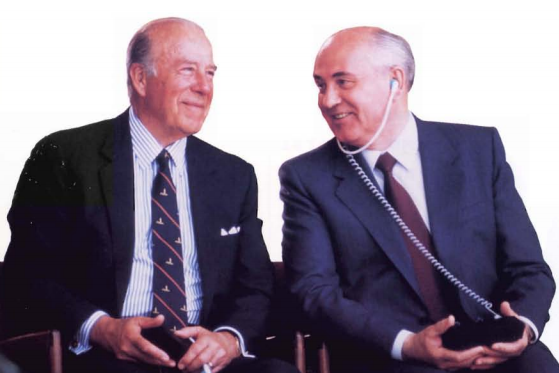

My friend, Mr. [George] Shultz, advised me to take as my theme the rule of law I-in the context, of course, of the political changes that have occurred in the world and, above all, in my own country, since 1985. Watershed periods in history may not be very comfortable for those who live in them, but they do, as a rule, at least stimulate deeper reflection and self-awareness. The Russian philosopher Nikolay Berdyayev once observed, “A division or split must take place in historical life and in the human consciousness to make possible an opposition between the historical object and the subject; reflection is needed for this historical awareness to emerge.”

It seems that we are today passing through just such a period of reflection-a period of acute sensitivity to human rights, to the rights of the individual-a period in which we rethink fundamental values.

One of these values is the supremacy of law in a governmental system. This is an essential premise of the new world order, about which views have greatly differed but whose idea has become unquestionably relevant.

The principles of the rule of law were proclaimed more than two centuries ago. Thomas Jefferson and the other Founding Fathers of the United States were among the first who tried to give them living embodiment. The “Spirit of ’76” fathered American democracy. The Declaration of Independence, and then the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, gave the initial impetus that, despite all deviations and setbacks, led ultimately to the emergence of the Western democracies and of states based on the rule of law.

The situation in Russia was quite different. For various historical reasons, and despite the profound and original insights of Russian philosophers, historians and jurists of the nineteenth century, no rule of law emerged in our country. Only in 1861 was serfdom abolished; our autocracy survived until 1917. “My will is law! My fist is the police!”- this, according to the nineteenth century critical literature, was the level of our legality. Therefore, one can hardly be surprised that the political struggle was dominated by extremist positions, which were fiercely, at times mercilessly, at odds. Progressive and democratic ideas were monopolized by the most radical factions. The stormy process of democratization following the overthrow of the autocracy rapidly led to the dictatorship of the Soviets. What Alexis de Tocqueville most feared in writing Democracy in America, and which America itself fortunately avoided, actually came to pass in Russia: the conversion of democracy into a democratic despotism. The law became pure decoration and, at times, nothing more than an arbitrary tool of the authorities. And the de facto lawlessness was justified by class expediency and as the “revolutionary legal consciousness of the masses.”

From there it was a short step to the emergence of the one-party police state. This occurred under Stalin, who brought the totalitarian state to its, so to speak, “peak of perfection.” And this regime, in its fundamental features, endured until 1985.

After the death of Stalin, even the top leadership more than once indicated an awareness that all was not well with the system. Partial reforms were attempted, but they did not affect the country’s political structure; they did not touch the Party’s monopoly of power. Hence, they were doomed from the outset.

What was needed was not isolated measures, on however large a scale, but an altogether different policy, a new political course. But for this, the necessary premises had to exist, both in society and in the governing levels of the state.

At this point, I must mention the dissident movement, whose influence extended to a substantial part of our society, especially to the creative intelligentsia, to the students, and even to some areas of the economic and Party governmental apparatus. The outside world also played an increasingly powerful role in the promotion of human rights and of a humanistic dimension as major components of normal international relations although this was done also with ideological aims.

“We can’t go on like this.” This sentence was first pronounced on the evening before the March 1985 plenum of the Party Central Committee, which after the death of Chernenko was supposed to elect a new Secretary-General, meaning, in our conditions, a new chief of state. This was actually the beginning of the new policy that later became known throughout the world as perestroika. Its purpose was to end the totalitarian system. Did the people who took this decision know what awaited them? Did they realize the scale of the task and its consequences? Inasmuch as this question is directed first and foremost at me, I will say: Yes, we knew the system-we knew it inside out. We realized full well how mighty and monolithic this monster was, welding together as it did the party machine and the state structures. One had to have this knowledge to have any hope of success.

I am asked many questions about my motives, about the reasons for my various positions and decisions. As you evidently know from reading the press, I am now working on my memoirs, where I will also try to answer these questions. I’m going to tell you how I made my choice and what I had to live through and think through; how my views evolved during the very process of perestroika. I hope that when this book appears, you’ll be willing to expend a certain sum of money to acquire it!

For now, though, let me just say that the philosophy and politics of perestroika, the policies of perestroika, went through several stages of development.

It was a difficult process, even a painful one. After all, those at the summit of power who had taken the initiative were themselves shaped by the very system that had to be changed. We wanted change, even radical change, but we remained part of this system. Therefore, our actions and our decision-making processes could not help but be affected for a while by the habits learned in our previous experience. And we had, after all, to take the realities into consideration. Politics is the art of the possible-the discovery of concordant interests in a framework of choice. Any other approach would be bossism or adventurism.

In any case, the choice was made in principle. That was the main thing. There were failures, errors, illusions, but the impulse to change things kicked in, and things started to move. From the very outset I saw the task as being one of unfettering the democratic process. Hence, we set our sights on respect for democratic rules, on getting people involved in genuine political activity. Hence the proclamation of glasnost and the struggle for its implementation.

But under our conditions, this was possible only through the Party and with the Party’s help. This paradox, as things turned out, contained a major threat to the cause of perestroika.

The incipient economic and democratic transformations disclosed such defects in our society that we soon found ourselves in an all-encompassing systemic social crisis. The reforms engendered opposition, and a political struggle commenced. But, at the same time, life demanded a more precise definition of our goals: the rule of law, separation of powers, freedom of speech and religion, a multiparty system, a variety of forms of property -including private property-market relationships, and reformation of the multinational state.

Nineteen-eighty-eight was a major milestone, that being the year we embarked on radical political reform. By that time, it had become clear that a partial reform of one or another piece of the administrative system would yield nothing. Everything hinged on the political system and on the de facto omnipotence of the Party apparatus.

The political reform affected the interests of many, and here I want to stress one point of principle that explains much that happened afterward. I am referring to the relationship between politics and morality. From the very onset of the crisis, I tried to avoid the violent, the explosive resolution of contradictions. I swore to myself as I stated in public more than once -that I would do everything possible to ensure that, for the first time in my country’s history, cardinal transformations would take place in more or less peaceful forms-without bloodshed, without the fragmentation of society, without civil war.

Therefore, I tried, by means of tactical moves, to give the democratic process time to get stronger. As President of the country I had many powers, including emergency ones. And more than once people tried to make me use them, tried to push me into an extremist position. As is known, this is something the self-styled Special Committee on the State of Emergency demanded of me during the August coup, but I simply could not betray myself.

Let me make a short historical digression. The policies of Alexander I in the beginning of his reign were considered rather liberal. He brought in the enlightened legal scholar Speranskii, who proposed a reform program. But who was at the side of Alexander I by the end of his reign? The brass-face Arakcheyev! The Arakcheyev regime and its methods of rule became synonyms for the most crude and arbitrary kind of despotism. Reformers throughout history have often passed through this sort of evolution. Probably the hardest thing to do is to keep the process of reform on its track. But I was firmly resolved not to deviate from my political choice, and my moral one.

Even today, my opponents, and even some of my supporters, like to call me irresolute. Many would like to be, or to seem, or at least to present themselves as, decisive politicians. But when put to the test, such decisiveness is only a flouting of the realities, violence against the people. And this is no longer politics at all. To me, decisiveness means sticking to my guns, pursuing profound transformations’ at the center of which lie the rights and liberties of the individual.

My approach, ultimately, allowed us to gain time-a very small amount of time when measured by historical standards, but still enough to build up sufficient democratic potential in society to act as a basis for further transformations.

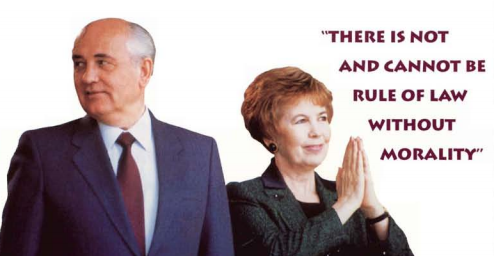

There is not and cannot be rule of law without morality. It is no accident that in both Russian and English the words “right” and “righteousness” have the same root. While a student of legal history at the university, I encountered the thinking of the religious philosopher Vladimir Soloviev, who said, “Law is the lowest limit or a certain minimum of morality,” and demanded that this minimum be realized. This is indeed how it is.

The function of the state authority is to ensure that legal standards are binding. In its ideal development the state must act only according to the law and according to justice, and any act of the state authority must have a basis in law. That is how I see the essence of the rule of law. The idea of the rule of law finds support in international law. Here the problem is that many of the norms of international law do not provide precise guidance for their domestic application. Hence, there arises the task of establishing sensible, practical ties between these two systems of law. And today this is simply a vital necessity in view of the interdependence and increasing integration of the world.

The second point of support is, of course, justice. Sometimes justice is viewed as the equivalent of the general principles of international law. The term is also used to mean the impartiality and judiciousness needed for the healthy application of accepted legal standards. I favor the fusion of law and justice in international affairs, just as this is done in states that are based on the rule of law. This is precisely how I visualize the new world order.

Authoritative mechanisms of international law whose decisions would be binding are needed to implement legal principles in international life. I have in mind first and foremost the International Court of Justice. I once proposed an agreement whereby states would recognize the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court in cases involving the interpretation of international agreements. Respect for international law is inseparable from respect for its institutions. It should cease being optional. The views of legal scholars should count for much here.

Our progress toward the rule of law has been difficult, as we are burdened by our dark heritage: the distorted attitude of our society toward law, the weakness and even absence of political culture in the overwhelming majority of our people, the historically conditioned disregard for law, our hostility toward those who are professionally responsible for the preservation of order.

Disrespect for legality was even manifested by those who at the end of last year were deciding on the fate of the Soviet Union as a state.

I was the initiator of the Novo Ogarevo process, which resulted in the production of an agreed-upon draft for a new Union Treaty. The August coup meant that it was never signed. With great difficulty, we were able to restore the Novo-Ogarevo process and develop a new draft Union Treaty that appeared to satisfy the leaders of the majority of republics. All the peoples of the country had before them the possibility of preserving their identity, of developing their national statehood-all this without violating historical continuity.

But a strange and unexpected thing happened. Behind the back of the President of the country and the heads of the other sovereign republics, behind the backs of the Supreme Soviets, three leaders announced that the union state had ceased to exist, and instead of it was created a Commonwealth of Independent States. The country was confronted with a fait accompli.

The events of December 1991 are described in detail in my soon-to-be published book. I was concerned only about the fate of the country, the state. 1was convinced that a new era in the country’s history must be begun with dignity and with the observance of legal norms. At this dramatic moment, I strove to do everything incumbent upon me to legalize and legitimize the emergence of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Once the formation of the Commonwealth had been sanctioned post-factum by the parliaments of the adhering states, I accepted this as a reality and announced my resignation from the presidency. My opinion of what occurred has not changed, but I am not urging a return to the past.

Unfortunately, the collapse of the Union has entailed terrible consequences confirming my own worst fears and warnings. New foci of interethnic conflict and contradictions have appeared. There have been flare ups of cruelty and violence in areas that had hitherto been quiet. We are now in an extremely serious crisis of legality.

But there are encouraging signs and tendencies.

I welcome the Russian Federative Treaty that was signed at the end of March. I hope that the integrity of the multi-ethnic Russian Federation will be retained, and that it will ultimately adopt a genuinely democratic constitution, within which framework the enormous problems now confronting Russia-including its position as successor state to the Soviet Union may more easily be solved.

Adoption of the constitution of the Russian Federation can become an important step in the transformation of Russia into a modern law-based state. But we should not flatter our selves. We are still far from that goal.

It must also be stated that the concept of a “social rule of law” is more in keeping with Russian traditions. This means the sort of interpretation of the individual’s constitutional rights that would include certain social guarantees. Such an approach would correspond to the expectations of the greater part of our society, and to the outlook of the majority of our citizens. Furthermore, it would psychologically lighten the task of becoming accustomed to living under the rule of law.

Ladies and gentlemen! Russia is experiencing difficult times, and is therefore in particular need of understanding and support. I welcome the program of international economic and financial assistance for Russia and the other countries of the Commonwealth that has been announced by President Bush. I am sure that everyone has a vested interest in the success of the present Russian leadership and its reform program.

I would like to conclude with an expression of hope and faith that Russia and the other countries of the Commonwealth-with the support of the world community-will preserve their democratic gains; will overcome their difficulties; will succeed in defusing hotbeds of conflict; will institute cooperation among themselves and with other countries, and especially with those major partners who, together with us, turned a major corner in world history during these past several years; and, I hope, will be able to enter the twenty-first century as civilized nations capable of making their own distinguished contributions to peace and the progress of humanity. Thank you.

President Gorbachev delivered this address on May 9, 1992, in Stanford’s Frost Amphitheater. He spoke in Russian while an English translation was simultaneously broadcast.

For publication, we began with the advance translation provided by Gorbachev’s staff. That text was then compared––by Eugene Ostashevsky of Stanford’s Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures––the the Russian audiotape of the actual Frost speech, and amended and updated accordingly.