Veterans Treatment Courts Practicum

As a former U.S. Army Captain, Sean Rosenberg, JD/MBA ’19, led rifle and reconnaissance platoons in Afghanistan. During missions his unit had a “type A, rub-some-dirt-on-it-and-let’s-go mentality,” Rosenberg says. But he commanded soldiers who had served multiple deployments and he saw that invisible wounds from combat, including the trauma of seeing friends and fellow soldiers severely injured or killed, couldn’t just be willed away. “It affected my soldiers in different ways. It would be extraordinary if you didn’t come back changed.”

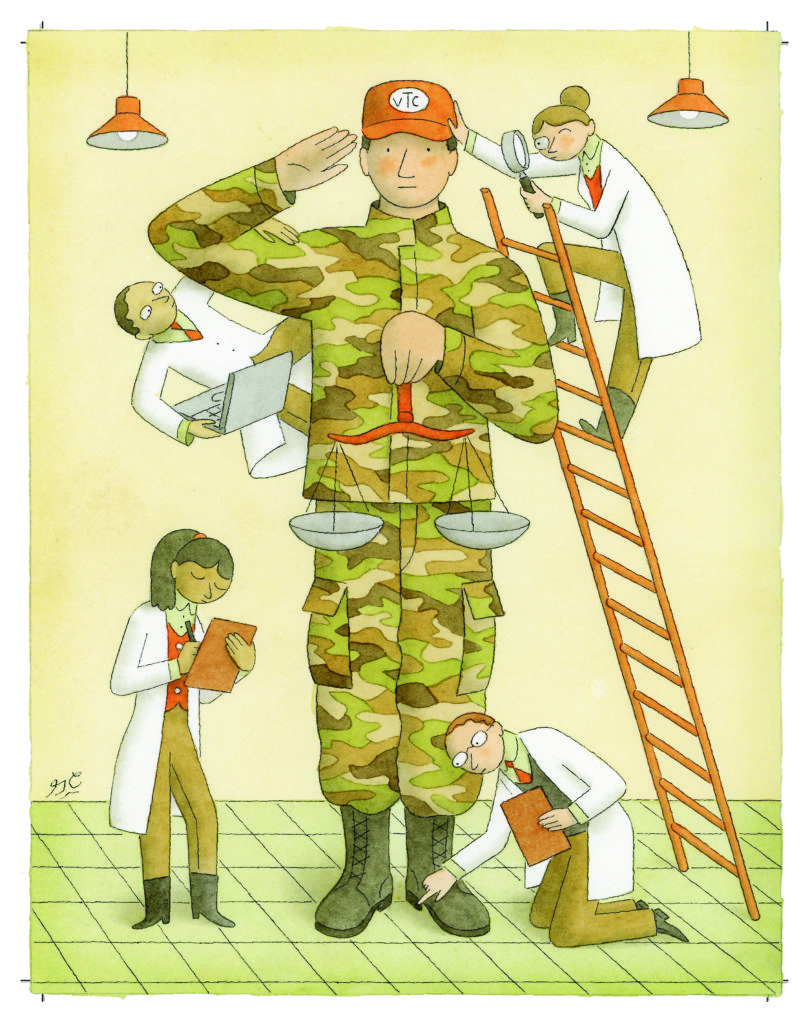

Long after they return from combat, many veterans are still coping with those experiences—and sometimes not very well. One study showed about a quarter of troops returning from Iraq and Afghanistan had mental health issues, and a quarter of those who saw combat may have suffered at least one traumatic brain injury. In recent years, the criminal courts have seen more and more veterans appearing as defendants with substance abuse and mental health issues that are fueling domestic violence, DUIs, and other crimes. That’s the bad news. The good news is an innovative court model to help many of these vets become productive citizens again, as Rosenberg and five students from Stanford Law concluded in Policy Practicum: Veterans Treatment Courts in spring of 2016.

First instituted in Buffalo, New York, in 2008, VTCs have expanded rapidly in recent years and there are now 300 across the country. But when Massachusetts Congressman Seth Moulton, himself a veteran, sought data in 2015 to help establish a VTC in his district, he realized that there were many variations on the basic model and few good measures of effectiveness. He reached out to Stanford Law School. Robert Weisberg, JD ’79, Edwin E. Huddleson Jr. Professor of Law and faculty co-director of the Stanford Criminal Justice Center, and Debbie Mukamal, executive director of the SCJC, agreed to create a public policy practicum aimed at sorting through some of those questions.

VTCs combine elements of both drug and mental health courts, which divert defendants into court-supervised treatment rather than incarceration. Unlike traditional courts, there is a team mentality rather than an adversarial posture among the prosecutors, public defenders, social service case managers, treatment experts, and volunteer veteran mentors. “The attitude is how can we make this work,” observed practicum student Jacob Raver, JD ’16, after visiting Santa Clara County Veterans Treatment Court presided over by Superior Court Judge Stephen V. Manley, LLB ’66.

The practicum found the criteria for those accepted into VTCs to be one of the most variable elements of their design. Manley’s court, as well as the San Francisco Veterans Justice Court, presided over by Superior Court Judge Jeffrey S. Ross, JD ’75, are considered among the most inclusive veterans courts. They accept defendants charged with violent and non-violent offenses and accept veterans regardless of the length of their service or the nature of their discharge. Some courts refuse to accept violent offenders. Others require a relationship between the veteran’s service, underlying diagnosis, and the crime committed. Practicum student Vina Seelam, JD ’16, who is now working in the public defender’s office in Alameda County, California, says she thinks the more inclusive policy is better: “Underlying causes of these crimes are often tied with aggression and violence,” she notes. “It doesn’t make sense to me to screen out those crimes. If you’re trying to reduce recidivism, it makes sense to have broad criteria.”

The students also noted that the commitment and enthusiasm of judges are key factors. “My interest in working with veterans goes back a long time because I’ve worked with the homeless for many years. I became frustrated that so many veterans were living on our streets and no one seemed to care about them,” says Judge Manley. He has worked with vets from Vietnam and previous conflicts, but was particularly concerned when “seeing people in mental health court who were relatively young, who were veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. I knew that was voluntary service and they did not generally have criminal records because they were screened going in. And yet they were committing crimes.”

The students found the underlying strength of local VA services to be an important factor in the success of these courts. David Grillo, veterans justice outreach coordinator from the Palo Alto VA, works in Manley’s court to help facilitate treatment plans. VTCs also tend to use volunteer peer mentors to provide extra support. Grillo notes that mentors have a key role. “There is a camaraderie about being around other veterans. It reminds them of a time in their lives when they were committed to a specific mission.”

Three of the six law students in the practicum are veterans. Gabe Ledeen, JD ’12, a military veteran who has advocated for the law school getting involved in veterans’ issues, lent support to the project as a facilitator. The practicum produced a report that urges more rigorous analysis of VTCs and sharing effectiveness data. The practicum found that jurisdictions tend to operate on “intuition and ad hoc” information in setting up courts and the criteria for success can be elusive. Judge Ross agrees that scientifically rigorous effectiveness data would be useful but creating a statistically valid study poses challenges. A reliable study would require randomly dividing veteran defendants into one group entering a treatment court and another remaining in the regular criminal court system and then comparing the outcomes. Because all qualifying veterans in San Francisco must be offered the opportunity to participate in such a court, those who decline are already indicating disinterest in treatment, which would invalidate the results.

Related issues involve defining success. Would recidivism include being arrested, or being charged, or being convicted, or violating a parole condition? And do you measure it for a year—or five years?

In some courts only those veterans who are eligible for VA benefits are accepted, which keeps costs to a county down. Veterans with a dishonorable discharge do not qualify for benefits. Ryan McIlroy, JD ’16, a member of the practicum who has returned to military service as a Judge Advocate General lawyer, says the practicum made him realize a veteran’s underlying mental health condition might also have contributed to the reason for a dishonorable discharge (such as substance abuse or assault). He keeps that in mind when advising commanders on the kind of discharge to seek for military personnel; otherwise, he adds, “the most in need may be ineligible for treatment.” Some courts, those of Manley and of Ross, for instance, fund treatment for ineligible veterans through either county programs or private grants.

Weisberg says VTCs reflect an evolution in U.S. culture trying to reverse the unfair stigma and neglect of Vietnam vets. However, it’s also true that VTCs represent a compromise with certain legal principles. For example, he notes, there is a general understanding that military service, particularly combat, can create conditions where an individual is more likely to suffer post-traumatic stress and, as a result, take illegal drugs or commit a crime. But in the traditional legal system, mental health and substance abuse are difficult to use as a criminal defense. “We can’t resolve these questions through abstract legal definitions, so we are going to do it through process,” he says. “We are accommodating mitigating factors through process rather than saying we are reducing your guilt.”

Drug courts have sometimes battled community concerns about giving drug users “extra” social services, and even Rosenberg admits that when he first heard about VTCs, he was a bit puzzled. “It seemed like a veterans benefit, like a get-out-of-jail-free card.” But after participating in the practicum, he now sees stopping the recidivism in these populations as a positive outcome that goes well beyond the veteran. “People are committing crimes over and over because the root issue isn’t being solved,” he says. VTCs “are solving issues and that’s good for the community, the justice system, and for the veteran.”

Joan O’C. Hamilton (BA ’83) is a San Francisco Bay Area-based writer with extensive experience in magazine journalism. Her work has appeared in Business Week, The New York Times, Stanford Magazine, and many other publications.