A Conversation with U. S. Senator Cory Booker: The Next 50 Years of Civil Rights and Racial Justice

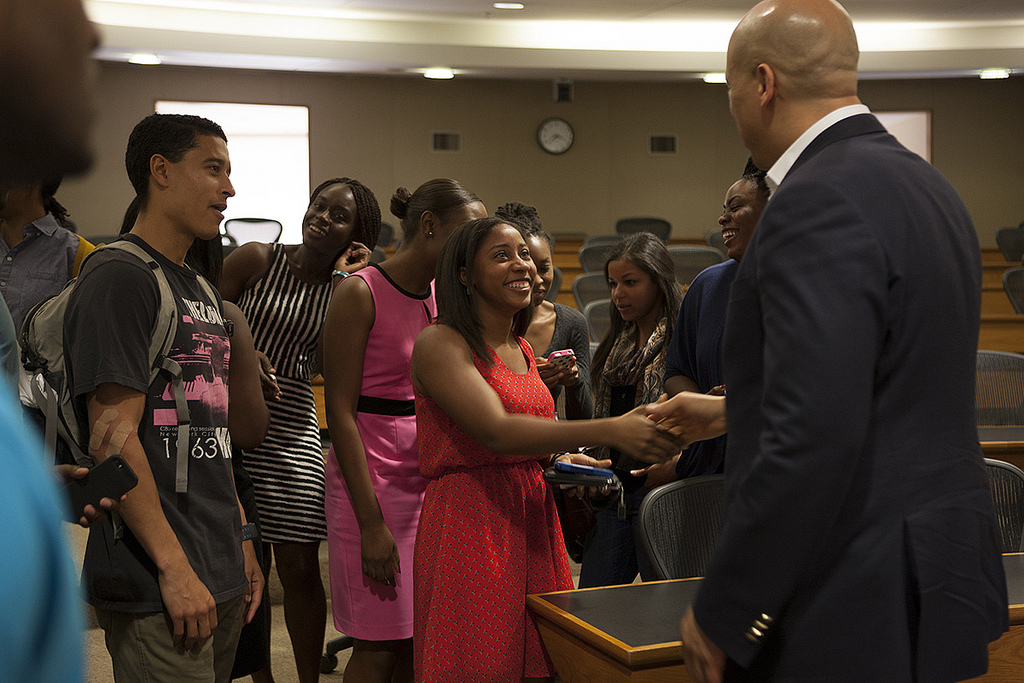

U. S. Senator Cory Booker walked into a packed auditorium at Stanford Law School on Saturday, February 22, smiling broadly and warmly greeting the assembled law students, some a bit stunned by his friendliness.

“How are you? Where you from? Oh, L.A.? Do you know so and so? You do! Well… .”

That casualness set the tone for an engaging discussion about race and social justice in America with Booker, BA ’91/MA ’92, who took time out from his busy Senate schedule to meet with 130-plus future lawyers. The talk capped off Stanford’s Black Law Students Association (BLSA) Black History Month events.

It was a relaxed Q&A format, with David Mills, professor of the practice of law, and a longtime friend of Booker, asking the questions. The two sat in leather club chairs and started things off with banter.Booker: “I’m surprised they came out on this beautiful Saturday.” Mills: “It was for me.”

M. Elizabeth Magill, Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Dean, introduced the two, noting that both are from New Jersey, their paths joined by a shared passion for civil rights and justice. In 1969, when Booker’s family became one of the first black homeowners in a middle-class suburban neighborhood, Mills was studying law and honing his civil rights skills at Rutgers-Newark.

Booker went on to study sociology at Stanford and law at Yale, becoming an Oxford Rhodes Scholar, an advocate for fair housing, and serving as a tech-savvy results-oriented mayor of Newark from 2006 until 2013. He is credited with leading a transformation of the city by reducing crime and fostering economic partnerships and growth. Booker won a special election in 2013 to fill the term of the late Senator Frank Lautenberg and became New Jersey’s first African-American U.S. senator.

Mills practiced law and founded several successful businesses while balancing his civil rights work and becoming co-chair of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. He launched the Mills Legal Clinic at Stanford Law School. He is a passionate advocate of prison reform who helped launch Stanford Law School’s Three Strikes Project and spearheaded the successful reform of California’s Three Strikes law with Proposition 36.

The conversation on Saturday quickly turned to one of the biggest civil rights and racial justice challenge in America today—its mass incarceration, which is the highest per capita among the industrialized nations—perhaps among all nations—and disproportionately affects people of color. Booker recalled when, just after his election to the U.S. Senate, his transition committees all reported back to him with the same suggestion for priorities: turning around mass incarceration was the common thread.

“Mass incarceration of nonviolent offenders is eroding human potential and squandering valuable resources,” said Booker. “We need to do more” to change that.

Mills asked Booker how mass incarceration and “extraordinary prejudice of people of color” can be addressed.

“This starts long before prison, with who is getting stopped by law enforcement,” said Booker. He shared with the audience the challenges of cities, where neighborhoods made up of mostly African-Americans were often those calling for more policing.

“As a mayor, you desire safer streets and one way to make that happen is with stop-and-frisk policing. Why not have it?” asked Mills.

“No—we can’t have that in a vacuum,” said Booker. He recounted his own experiences with unwarranted police stops—both in New Jersey and in Palo Alto.

“My parents had to give me instructions on what not to do in those situations so I wouldn’t get shot,” he said. “As a privileged kid in the suburbs, the stops were an inconvenience. For other kids, the experience could be traumatizing.”

When Booker was mayor of Newark, he looked for ways to help reduce the need for stop and frisk in his city— and to break the prison cycle for kids who were clearly at risk. That meant more community interaction with law enforcement and early intervention in troubled areas. He estimated that most street-corner drug dealers don’t even make minimum wage and that they need to be made aware of other options. “We need to mend fences in neighborhoods and build up trust. But this is going to have to be a nationwide effort.”

Mills wondered if the issues of crime and mass incarceration were about fiscal sensibility or fairness—and whether it was a more bipartisan issue than we realized.

“On my first day in the Senate, Rand Paul introduced himself and said he looked forward to working with me on these issues,” said Booker. “There is some agreement with Republicans and Tea Party members on these matters. And I’m thrilled to have colleagues on both sides of the aisle to work with on this.“

Mills followed up by asking how mental illness plays into the situation, with a significant percentage of the nation’s incarcerated suffering from it.

“I don’t know of any legislation dealing with this issue now, but I do know from my experience as mayor that we need to address it. If we lower mandatory minimum sentencing, we save millions of dollars. I would propose that we do that—and then divert the savings to helping the mentally ill,” said Booker. But the real frustration, he added, is how upside down our funding is. “We know that it is much less expensive, both in dollars and in lost human potential, to offer prenatal and early childhood development programs and education. These things that help people are less expensive than picking it all up after someone has committed a crime and gone to jail.”

Booker and Mills both talked about the ebb and flow of racial and social justice, successes amid the frustrations of progress stalled, the tragedy of youthful lives lost, like that of Trayvon Martin. But Booker sounded a note of optimism.

“Racism is a sad reality of our society,” he said. “But my experience gives me hope. I know we are making progress. When the kids of Newark saw a black man and his family in the White House, it affected them. It gave them hope too.”