Stanford’s William Gould on SCOTUS NCAA Student Athlete’s Decision

On Monday, June 21, the U. S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) cannot bar relatively modest payments for expenses to student-athletes. Here, Stanford Law Professor William B. Gould IV, former chairman of the National Labor Relations Board, discusses the decision and other cases urging pay for student athletes and challenging the NCAA’s control of those students.

How significant is this decision?

I think it’s a very significant decision. The student athletes won a major victory in this ruling today. The holding is a narrow holding. It upholds Judge Claudia Wilken in Oakland of the US District Court, who held that education-related expenditures, many of them subsequent to graduation or their college experience, were appropriate to be ordered for student athletes. And her holding really flies the tree tops in that these are modest payments that are education-related.

I think that Justice Kavanaugh’s opinion today will resound for years to come. Coupled with the Court’s refusal to give deference to universities and the Court’s recognition that the market has expanded so considerably to the benefit of universities, makes me think this is just the first shot across the bow.

But it’s a broader antitrust decision, right? What will it mean for universities going forward?

The impact of the Supreme Court’s decision goes considerably beyond the narrow holding because the Court said that universities and educational instructions are like any other industries that can violate antitrust laws through anticompetitive practices. And the Court said that while judges should not micromanage the business of college athletics, the reality is that the market has changed considerably over the past four decades and today’s holding opens up the universities to a wide variety of challenges involving the expenses reimbursements beyond those allowed for today. The fact that the Court is no longer going to treat universities—the NCAA— in a special way and different from other industries is very significant.

What did you think of Justice Kavanaugh’s opinion?

Justice Kavanaugh’s opinion is what I call an emperor’s clothes opinion. He said the universities have no clothes and they are naked for all to see and they are engaging in the same kind of price fixing that other industries would be condemned for. Justice Kavanaugh focused in particular on the enormous pay inequities—of university presidents, athletic directors, coaches and others—that they are getting paid millions, and the players, who are disproportionately African American and low income, and are getting virtually nothing.

The combination of the Court’s unwillingness to continue giving deference to universities and their organizations, like the NCAA, coupled with the direct talk of Justice Kavanaugh is going to put the universities and the NCAA on notice that they face future litigation unless they come to grips with the business of providing further compensation to student athletes.

What types of expenses does this ruling cover?

Education related expenses like money for graduate programs, computers, and the like. The NCAA has been increasing compensation over the years—all kinds of money goes to athletes. But the NCAA artificially caps compensations. Judge Wilken expanded those expenses. And the Court upheld her ruling. Thus far, that’s as far as we’ve gone.

Does the Court support going further to perhaps salary compensation for student athletes?

No, because the Court, or at least Justice Gorsuch’s opinion for the Court, assumes that the basic objective can be some kind of demarcation line, however artificial it is, between so-called professionals and so-called amateurs. Presumably, salary compensation, at least the kind professional athletes might obtain, would not be, in this Court’s view, appropriate.

Today’s decision does not address the labor rights issues that some student athletes have raised and the need to be paid for their time, right?

Not at this point. Colleges have been constrained by the NCAA so cannot offer pay. But some athletes have sued saying they are entitled to compensation just like other students are—like those working in the cafeteria or book store, who are entitled to at least minimum wage. So, some students have sued for violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which entitles all employees to minimum wage and premium pay for overtime. There has been no major success on this so far at the Appellate Court level, but some courts have indicated that the right set of circumstances might allow them to entertain such a suit. ( For more on this, see Gould’s article American Amateur Players Arise: You Have Nothing to Lose But Your Amateurism, 61 Santa Clara Law Rev 159 (2020)

Yet many student athletes spend so much time on their sports that they can barely fit in academics, let alone a part-time job.

There was a detailed opinion by Peter Ohr, now the acting General Counsel of NLRB about the time and effort that these students put into their work as athletes—spending 40-60 hours a week on athletics alone—and the control that universities have over them. This is an enormous scandal that is just now being recognized. And I think the Court’s decision today will focus on these realities.

I do see the wage argument as a strong one. And the courts seem to be moving gradually in that direction. The Fair Labor Standard Act asks if they are entitled to a wage and overtime. And in many ways may prove to be more important.

What does the Supreme Court’s decision mean for these other cases— labor related and image rights?

Nothing in the Court’s opinion affects the play-for-pay legislation that California and other states have been enacting, which allows athletes to be compensated for the use of their images and the like. That will not be affected. Several states are proceeding with their own legislation, in addition to the cases brought by student athletes. And it looks like the NCAA and universities are not going to be able to get Congress to bail them out of this through legislation. So that is a bigger battle field than the one they just faced.

What was the main argument put forward by the NCAA for not enhancing student athlete expenses?

The NCAA and universities have been saying that enhanced compensation would detract from the popularity of these sports, that the public would not be as interested in these sports or be willing to pay to see these sports, if the players are getting compensation akin to salaries. Well, Judge Wilken made a very interesting point, and her careful fact-finding analysis backed it up, that no one had shown that the NCAA’s argument that enhanced compensation for student athletes will somehow diminish the attractiveness of the product— the product being football and basketball, etc. And the Court praised Judge Wilken for her fact-finding and conclusions. Justice Kavanaugh said that the NCAA’s argument was circular and unpersuasive.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

By recognizing universities as employers who are performing a function akin to other companies, the Court has invited a new wave of litigation.

Also, I think the NCAA made a bad gamble. They thought they could get something from this conservative Supreme Court to help them with this antitrust case and other areas. But they made a bad bet. They rolled the dice—and thought the Court would roll back Judge Wilken’s decision and roll back not only the antitrust cases but the play-for-pay protective legislation as well as the right to be called employees and to collect a minimum wage and overtime.

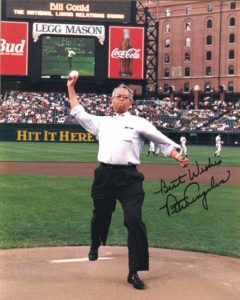

William B. Gould IV, the Charles A. Beardsley Professor of Law, Emeritus, at Stanford Law School, is a prolific scholar of labor and discrimination law who has been an influential voice in worker–management relations for more than fifty years. Gould served as chairman of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB, 1994–98) and subsequently served as chairman of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board (2014-2017). He has been a member of the National Academy of Arbitrators since 1970. Early in his career, he served as a consultant to the EEOC and lead counsel on key employment discrimination cases. Gould was recently appointed by San Francisco Mayor London N. Breed to oversee an independent and comprehensive review of the city’s workplace policies and practices with a focus on claims of bias, harassment, discrimination, and retaliation.

Read Stanford’s William Gould on SCOTUS Labor Decision Cedar Point Nursery

Gould’s most recent scholarship includes A Primer on American Labor Law (6th edition. 2019), and For Labor to Build Upon: Wars, Depression and Pandemic, New York: Cambridge University Press (forthcoming 2021).