SLS’s Hank Greely Breaks Down the Alabama Wrongful Death Case Involving Frozen Embryos

The Alabama Supreme Court issued a February 16 decision finding that embryos created through in vitro fertilization (IVF) should be considered “unborn children” and thus could be the subjects of civil suits by the prospective parents for wrongful death. Several of the state’s IVF clinics, including the state’s largest at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, have since paused their IVF services as they analyze their liability risks. The ensuing national discussion has focused on how the decision might affect IVF in Alabama and nationwide, and whether the ruling is an extension of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade.

On a recent episode of the Stanford Legal podcast, Hank Greely (BA ’74), the Deane F. and Kate Edelman Johnson Professor of Law and the director of the Center for Law and the Biosciences, explained why he thinks the Alabama decision is not likely to have a significant long-term impact on IVF. Along with the podcast co-hosts Richard Thompson Ford, the George E. Osborne Professor of Law, and Pamela Karlan, the Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Professor of Public Interest Law, Greely analyzed the Alabama case and provided insight on some of the law and the politics around IVF. Greely specializes in the ethical, legal, and social implications of new biomedical technologies, particularly those related to genetics, assisted reproduction, neuroscience, or stem cell research.

The following is an edited excerpt of the full interview, which can be found here.

Ford: Hank, can you give us some background about the decision?

Greely: This is a weird case. Three couples filed wrongful death suits at the trial court level. It was never tried. It was decided on motions to dismiss. The claims here are odd, almost to the point of bizarre. They claim that some patient at the fertility center was walking around unguarded and reached into a vat cooled by frozen nitrogen, took out a little stick that had frozen embryos in it, burned his hands on the cold nitrogen, dropped it and destroyed the embryos. Because the case was never tried in the lower court, and there was no discovery, those are the facts that the Alabama Supreme Court had to rule on.

At issue was the Wrongful Death Act enacted in Alabama in 1872. In common law, there was no cause of action for wrongful death. So every time a relative sues to try to get damages for the death of a relative in the United States, those are all statutory. Different states and the federal government have enacted slightly different wrongful death statutes. Alabama did it in 1872. At some point in the 20th century, Alabama added language that made it clear that the statute applied to an unborn child. This was the result of a case brought when a woman was injured and the fetus she was carrying died. She sued and the legislature then amended the law to include unborn children.

Karlan: It’s a little bit like the famous Keeler case in California where somebody assaulted a pregnant woman and kicked her in the stomach, causing her to miscarry.

Greely: There are two different aspects to that too, Pam. One, is there a criminal cause of action for the death of the fetus? And then is there a civil cause of action from the parent or parents for the death of the fetus? The Alabama case is only about the civil cause of action, the wrongful death statute. And frankly, the Alabama courts had bounced back and forth a couple of times before it decided that if the fetus is killed, whether viable or not, there is a cause of action for wrongful death.

One of the things that’s really important about a wrongful death cause of action, and what one of the justices points out quite nicely, is this is really a case about punitive damages. Because you can’t get punitive damages under the other kinds of theories that the plaintiffs might have had for destruction of the embryo. But in wrongful death cases, if it’s done with malice, oppression, and fraud, or gross negligence, or whatever the state standard is, you can get punitive damages.

Karlan: Right, so if they just had lost a piece of property that was in a test tube that someone broke, that’s not going to allow for punitive damages.

Greely: Right. This was an effort by lawyers to get another cause of action to apply to this very odd, and, I have to say, suspect facts alleged in this case. They also brought the more traditional loss of property, etc. issues, which the majority dismisses as moot.

The lower court dismissed all the claims. There was no intermediate appellate court review in Alabama for this case; it went straight to the Alabama Supreme Court, which has nine justices. The nine justices split six to one to two. Six joined the majority opinion, one concurred only in the result, one concurred in part but dissented on the main question, the wrongful death issue, and another one dissented on everything.

It’s a decision that the majority opinion quite clearly grounds in the 1872 wrongful death statute as amended. And it’s a decision that the majority says, “Though there are all these huge implications, ethical, 14th amendment, etc., etc., we’re just looking at the statute. And by God, we are originalists. So we’re just looking at what the statute meant then.” And, they say, the statute in 1872 meant all children, children included unborn children, and that unborn children clearly at that time would have encompassed frozen embryos.

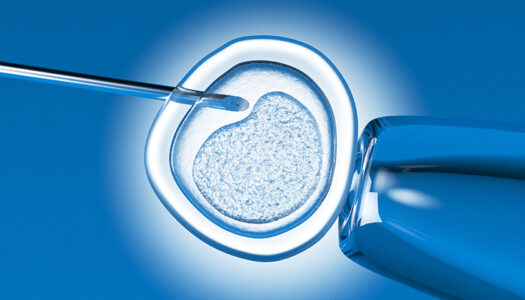

Karlan: Let’s backtrack for a moment. Can you explain what, exactly, is a frozen embryo?

Greely: Normally, the tough part of IVF is egg harvest. Getting mature eggs from a woman requires an expensive, unpleasant, and somewhat risky series of shots to hyper-stimulate the ovaries. You then take those eggs out and you mix them with sperm. This is one of those areas where life is unfair because sperm harvest for men is typically not unpleasant, risky, or expensive. You fertilize those, you’ve got embryos. You’ve got single-celled fertilized eggs, also known as zygotes. With a healthy young woman, you’ll get somewhere between 0 and 30 eggs, usually around 10 to 15.

Karlan: So they can get all these eggs, but very few of these people presumably want 10 or 15 children.

Greely: That’s correct. There are occasional exceptions, but for the most part, they want one, two, three, and typically they want them spaced out in time. So you grow this from a zygote for about five or six days in a Petri dish, in a laboratory. At five or six days, it’s about 100 to 200 cells. It’s barely visible to the naked eye if you’ve got good eyes and the lighting is right. And under a microscope, it looks like a soccer ball. The outside of the ball is called the trophectoderm, which eventually becomes the placenta and the other supports for any pregnancy. The interior of the ball has a few cells called the inner cell mass. They become the embryo, the fetus, the baby–the law professor, ultimately. At that stage, you can transfer embryos, usually on day six in the U. S., into the uterus of a woman who’s going to carry them, or you can freeze them. Freezing has been done for about 40 years now and got a lot better about 10 or 15 years ago.

So, we’ve got these frozen embryos, allegedly an idiot walks around, grabs some, breaks their container, and kills the embryos. I would note that negligence problems in IVF labs are not new. A few years ago, hundreds of embryos were destroyed in a clinic in San Francisco. Hundreds more were destroyed in a clinic in Cleveland. These were not idiot patients walking around. These were failures of the clinics’ freezer systems.

Ford: Sometimes the embryos are destroyed negligently. Sometimes they’re destroyed on purpose because there are 20 and the parents only want two children. And this is relatively widespread. So what’s been the implication of this Alabama decision for the general practice of vitro fertilization?

Greely: Outside Alabama, I don’t think it’s had any effect now other than probably clinics calling their lawyers to say, “Hey, does this have any effect on us?”

Karlan: So why did the University of Alabama Birmingham Clinic announce they’re pausing their IVF work?

Greely: I think because they’re talking to their lawyers. There are two things they could be worried about. One clearly is a problem for Alabama IVF clinics coming out of this opinion. Now, if they’re sued for negligent destruction of embryos, they’re potentially on the hook for wrongful death damages, which can be significant, and potentially for punitive damages. These were not in the cards before. So, their liability risk has gone up for negligent destruction or damage to embryos.

The bigger issue is what happens if they’re destroyed on purpose. This opinion does not directly speak to that. It doesn’t say these embryos are persons, just “unborn children” for purposes of the wrongful death act. It doesn’t even say that they are unborn children for purposes of criminal liability. There’s a long discussion in the decision about the interaction between the criminal and civil statutes. The majority expressly says there does not necessarily mean there’s criminal liability. What it says is there is wrongful death liability. Who would be a plaintiff in a wrongful death civil suit involving frozen embryos? The prospective parents. If the prospective parents have said, “Destroy my embryos,” that’s not going to be a good thing for their wrongful death case.

Ford: So Hank, could you tell us a little bit about some of the other opinions of the case? You mentioned that the Alabama Supreme Court was split.

Greely: The majority opinion, just as a matter of reading case law, and even from their originalist perspective, is deeply flawed. Three of the other opinions point that out in great detail, how irrational and illogical some aspects of the majority opinion were. Those three opinions are, I think, technically good and very professional. But, in the “not good” or “professional” category, the opinion that stands out is by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama, Tom Parker. Justice Parker has been in the news before. He is a fervent Christian and it shows in his concurrence. He does make an effort to present his theological quotations in a way that makes them seem legitimate to talk about it. He says, “Well, what we’re interested in is what the people of Alabama meant when, in 2018, they added a constitutional provision about the sanctity of life.” (The meaning of this amendment for the case in question was disputed in the various opinions; it was clearly not decisive.) But in talking about the sanctity of life, the Parker opinion says: here’s what the people of Alabama meant. And it’s all about God—a Judeo-Christian God, though I’m not sure about the “Judeo” part of it.

To me, he is saying that the Constitutional amendment embedded in Alabama law is an explicitly religious view of the sanctity of life. If so, I think he’s saying the Alabama Constitution violates the First Amendment by being an establishment of religion. He goes beyond saying the people were largely motivated by religion to saying they enacted this religious position, that all human life is sacred because it is made in God’s image and God gets really angry if you mess with his image. It’s really quite an astounding opinion. It is a concurrence. It’s not the majority opinion, but it’s out there.

Listen to the Stanford Legal Podcast with Hank Greely

Ford: This leads to the question that may be on many listeners’ minds: How is this related to the recent Supreme Court opinion in Dobbs that overturned the right to privacy and reproductive liberty established in Roe v. Wade? Is this Dobbs 2.0 moving us in a direction of something like fetal personhood?

Greely: I actually published an article in July 2022, just a few weeks after Dobbs came down, talking about the implications of the death of Roe, because even before Dobbs, it was obvious that Roe was about to be killed. In it, I said I don’t think there is going to be much of an effect in terms of embryos created for IVF. because IVF is popular. People like IVF. Even pro-life people like IVF. Of course, some don’t. The Vatican certainly doesn’t. And there are some who want fewer embryos destroyed as part of IVF. But IVF is genuinely popular. Now, I actually think I was right. But that makes this decision a bit of an embarrassment for me. I was thinking about legislatures and referenda. I wasn’t thinking about very, very conservative Supreme Courts coming out with wide and wild statements.

Technically Dobbs has nothing to do with this. Roe was never applied to embryos outside of a woman’s body, and its application might’ve gotten a little tricky given that the interests of the woman carrying the fetus were stressed in the cases involving reproductive freedom and reproductive liberty. But as I noted in the article, important cases are not just “law things,” they’re “political things” too. Dobbs was a big shot in the arm for the anti-abortion movement. It’s an affirmation of what they had been working at for 49 years. But that leaves all these organizations with the question, what do we do next? Where do we go now? We have an organization. We have people. We’ve got motivation. Where do we go? One of the places I think they would like to go is further protections for embryos. That’s when I say IVF is probably safe because IVF is popular. But things like embryo research or various genetic tests on embryos to determine sex or disability status, those are things where I think the political forces energized by Dobbs will focus.

Karlan: Looking at this, it seems to me that this is like a dog that has caught the car it was chasing, that nobody expected when they said life begins at conception, that it was going to potentially cause problems for people who want to have children.

Greely: I think that’s right. And now the dog has to decide “what in the world am I going to do with this thing?” And what I will be watching most closely is what, if anything, the Alabama legislature does. I think there’s a very good chance, even if it is the hardest core pro-life legislature in the country, that it’s going to exempt IVF because IVF has a lot of political support.

Karlan: There’s a bill pending in Congress, the Life at Conception Act, that 120-something Republican House members are currently supporting that declares that the term “human being” means at all stages of development, including the moment of fertilization. Do you think this is going to put some brakes on bills like that?

Greely: I think what will happen with bills like that is a carve out for IVF. And they’ll say, “except for embryos created as part of in vitro fertilization,” or “nothing here is intended to interfere with the normal processes of in vitro fertilization.” We actually saw that in an Oklahoma bill a few years ago and that’s my guess about where things will go. But I have to say, if the last seven years have taught me anything, it’s that my guesses about American politics are a lot worse than I thought they were. [A few days after this Stanford Legal interview, the Alabama legislature moved to protect IVF in the state.]

Ford: It sounds like the upshot is that this may not be quite as bad for in vitro fertilization as many people thought. But it suggests a clash between the politics on the one hand and the theological conceptions underlying the pro-life movement on the other. It’ll be interesting to see how the pro-life movement manages that tension, with the implication that you’d be potentially outlawing something that’s quite popular, but does implicate many of the arguments that are made against abortion.

Greely: I would add that it’s probably not as bad for IVF as people have initially thought and will increase some costs and liability in Alabama. But it could be bad for IVF if the Alabama Supreme Court takes some of the language in its own opinion, let alone that of Chief Justice Parker, and runs with that. This could lead to the death of IVF in Alabama. But I think that is unlikely.

Read a Prior Q&A with Professor Greely on IVF Post-Dobbs

Henry T. (Hank) Greely specializes in the ethical, legal, and social implications of new biomedical technologies, particularly those related to genetics, assisted reproduction, neuroscience, or stem cell research. He is a founder and past president of the International Neuroethics Society; a former member of the Multi-Council Working Group of the NIH’s Brain Initiative and former co-chair of its neuroethics working group; and chair of California’s Human Stem Cell Research Advisory Committee. He chairs the steering committee for the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics and directs the law school’s Center for Law and the Biosciences. Greely is also a professor (by courtesy) of genetics at Stanford School of Medicine.