Designer Babies: An Ethical Horror Waiting To Happen?

Summary

Comfortably seated in the fertility clinic with Vivaldi playing softly in the background, you and your partner are brought coffee and a folder. Inside the folder is an embryo menu. Each embryo has a description, something like this:

Embryo 78 – male

• No serious early onset diseases, but a carrier for phenylketonuria (a metabolic malfunction that can cause behavioural and mental disorders. Carriers just have one copy of the gene, so don’t get the condition themselves).

• Higher than average risk of type 2 diabetes and colon cancer.

• Lower than average risk of asthma and autism.

• Dark eyes, light brown hair, male pattern baldness.

• 40% chance of coming in the top half in SAT tests.

…

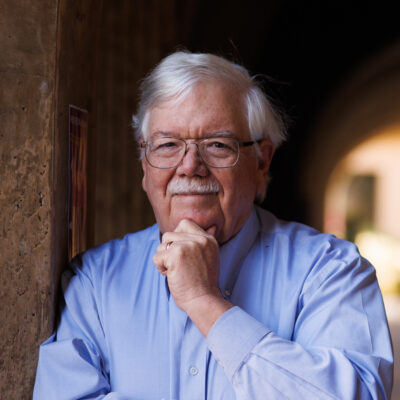

Besides, there seems to be little need for gene editing in reproduction. It would be a difficult, expensive and uncertain way to achieve what can mostly be achieved already in other ways, particularly by just selecting an embryo that has or lacks the gene in question. “Almost everything you can accomplish by gene editing, you can accomplish by embryo selection,” says bioethicist Henry Greely of Stanford University in California.

…

For now, though, if there’s going to be anything even vaguely resembling the popular designer-baby fantasy, Greely says it will come from embryo selection, not genetic manipulation. Embryos produced by IVF will be genetically screened – parts or all of their DNA will be read to deduce which gene variants they carry – and the prospective parents will be able to choose which embryos to implant in the hope of achieving a pregnancy. Greely foresees that new methods of harvesting or producing human eggs, along with advances in preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) of IVF embryos, will make selection much more viable and appealing, and thus more common, in 20 years’ time.

…

As a way of “designing” your baby, PGD is currently unattractive. “Egg harvesting is unpleasant and risky and doesn’t give you that many eggs,” says Greely, and the success rate for implanted embryos is still typically about one in three. But that will change, he says, thanks to developments that will make human eggs much more abundant and conveniently available, coupled to the possibility of screening their genomes quickly and cheaply.

Read More