William B. Gould IV

Stanford Law’s First Black Faculty Member Celebrates 50-Year Milestone

1954 was a pivotal year for William B. Gould IV.

He was one of only two Black students in the college prep track at Long Branch High School in New Jersey when the Army-McCarthy hearings took place.

“At the end of the school day, the principal and I would watch it together,” Gould recalls of the televised hearings held to investigate conflicting accusations between Sen. Joseph McCarthy and the U.S. Army. “My father worked at Fort Monmouth, which was the installation that was being investigated by McCarthy, so we had personal experience with that.”

Then came the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, and Gould’s path in life became clear to him.

“I had been attracted to the Episcopal priesthood. My father brought me up with the idea that, as the Book of Common Prayer says, ‘Come unto me, all you that travail, that work and are heavy laden,’” Gould says. “I had this interest in religion that sort of linked to law. And these events heightened my interest in the law. Of course, Thurgood Marshall’s picture was on the cover of Time magazine, and I followed the cases that he was arguing very closely.”

Gould studied history and political science at the University of Rhode Island and met Marshall after the justice visited campus. During summer breaks, he worked at the local A&P grocery store lifting and carrying heavy boxes—and then, as a member of the Utility Workers Union, breaking up roads with a pick and shovel. He understood what it meant to be a laborer and saw unions as progressive—but also as tools to keep minorities and women out of good-paying jobs.

“Some unions were an obstacle to desegregation. And some of the unions, like the industrial unions that emerged in the 1930s, were promoters of civil rights and equality. That made me look in the direction of union law,” he says.

Gould was fortunate to find a mentor at Cornell University Law School in his 1L legal research professor Kurt Hanslowe, who devised a problem for the class that combined labor with civil rights law. “Of course, I took to it like a fish takes to water. And I wrote a paper that brought me to my professor’s attention,” Gould recalls. He heard Walter Reuther, then president of the United Auto Workers, speak on campus—and was inspired by him. And subsequent to his professor’s recommendation, Gould was offered a summer job at the UAW’s general counsel office. “I was really excited by this opportunity. It was 1960 and I earned the princely sum of $80 per week.”

Watch an in-depth interview of Bill Gould with Dean Jenny Martinez below.

He found spiritual satisfaction in the study of labor law—and intellectual inspiration.

“The statute—the National Labor Relations Act—was and is so intellectually fascinating. It was like a mosaic with so many different portions to it. I loved it, and I love it to this day,” says Gould. “But, as I point out in my new book and a number of my other books and articles, it has become such a failure.”

Gould counts off the promises of America’s founding labor law, passed in 1935. The right to organize. The right to protest without fear of retaliation. The ability to engage in collective bargaining so workers could shape their own destinies. The right to freely associate with one another. “I was excited about it because it contains a kind of bill of rights for workers—a Magna Carta for the workforce. And it has lasted longer than any other legal framework in any other industrialized country in the world,” he says. “But whatever the promises it held on paper, those promises weren’t fully delivered to America’s workers.”

The NLRA—its potential and failings—has been the focus of much of Gould’s scholarship, legal practice, and government service for some six decades.

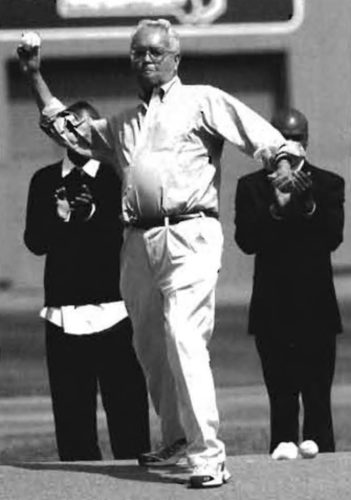

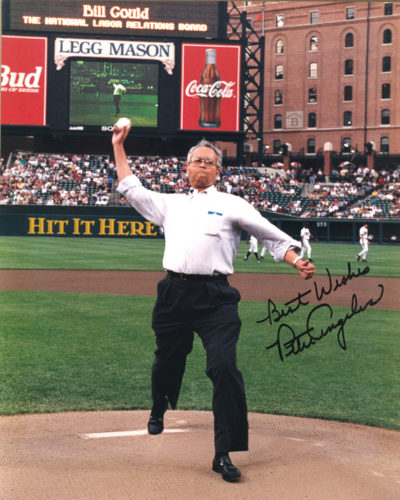

A world-renowned labor law scholar and practitioner, Gould has litigated groundbreaking cases and held key positions in government service, including as President Bill Clinton’s chairman of the National Labor Relations Board (1994–98), the first Black person to hold the position, where he played a critical role in bringing the 1994–95 baseball strike to its conclusion. He also served as special adviser to the Department of Housing and Urban Development on project labor agreements from 2011 to 2012 and was later appointed chair of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board by Governor Jerry Brown, where he served from 2014 to 2017. More recently, Gould served as Independent Reviewer on Equal Employment Opportunity for Mayor London Breed of San Francisco from 2020 to 2021. An influential voice in worker-management relations who has arbitrated and mediated more than 300 labor disputes, he also helped to establish the field of sports law.

And throughout, he has been a publishing engine, helping to shape critical labor and sports issues with 11 books (including A Primer on American Labor Law, now in its 6th edition), roughly 60 journal articles, and dozens of opinion essays.

This year, Gould, Charles A. Beardsley Professor of Law, emeritus, marks his 50th year on the Stanford Law School faculty with the publication of his latest book, For Labor to Build Upon: Wars, Depressions and Pandemics, a sweeping historical analysis of American labor laws and unions, from the burgeoning growth of the movement in the 1930s to today’s upsurge in union organizing after decades of decline, with gig workers, Starbuck’s baristas, and Amazon warehouse workers joining college athletes and PhD students to sign up.

Prolific Scholarship Arguing Ground Breaking Cases

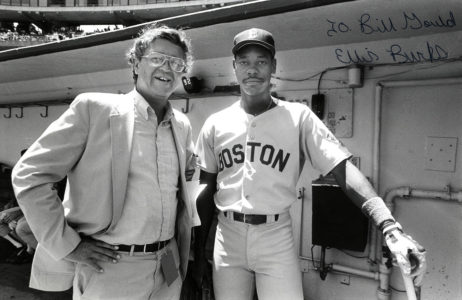

Bill Gould’s office at SLS is a chaotic burst of work in progress and career accomplishments, with stacks of books and paper files of new scholarly projects, alongside memorabilia that capture a career in law and government service.

The baseball mitt? A gift from Willie Mays who visited Gould’s sports law class in the 1980s. The room is a visual tour of Gould’s career with cherished photos of him with everyone from former president Clinton to Nelson Mandela and Dusty Baker.

The keepsakes are touchstones of critical labor issues gathered over the course of his career, which began when Gould graduated from Cornell Law School in 1961 and took a position as an assistant general counsel with the United Auto Workers in Detroit. He left after a year for a graduate program at the London School of Economics to study comparative labor law with the famed labor scholar Otto Kahn-Freund.

“Otto was really the doyen of comparative labor lawyers,” says Gould. “A lot of my professional career—its impetus in terms of intellectual growth—is owed to that year at the LSE.”

Gould returned to the United States and served as a junior lawyer for the National Labor Relations Board in Washington, D.C., before entering private practice with Battle, Fowler, Stokes & Kheel in New York, where he represented Teamster locals and arbitrated disputes in maritime, transit, and other industries. He wrote frequently (his first law journal article was published in 1961) and he caught the attention of Wayne State Law School in Detroit. When he agreed to join its faculty in 1968, it was on the condition that he would still have time to represent clients. “I began to really write. I think I published five journal articles in one year. It was a very productive time, fueled in part by the Edison case,” he says.

Stamps v. Detroit Edison was one of the first racial discrimination employment cases in the country, and Gould’s clients were Black workers at Detroit Edison who had been denied admission to the higher paying career track and steered instead to lower paying unskilled jobs, regardless of their qualifications.

“A number of Black workers from the Detroit Edison Company came to my office and they told me about the problems they were facing. I remember thinking two things. One, that I needed to help these guys. Two, that what they were describing to me was what I had been talking about in my seminar,” says Gould, who had developed the first employment discrimination law seminar at Wayne State, as well as the first at Stanford a few years later. “There was hardly any case law on the subject at the time, so I had gathered the materials over the years and put the seminar together.” Gould argued Edison in 1973 and was awarded comprehensive remedy including punitive damages and, for the first time in a U.S. ruling, front pay compensation for future opportunities as well as back pay for lost opportunities. “We broke ground with that case. And got $4 million for our clients—the highest award at the time—plus $250,000 in attorney fees, which I donated to the ACLU, which, at the behest of my old friend Mel Wulf, then the legal director, had bankrolled the case. But it was the biggest employment case win at the time.”

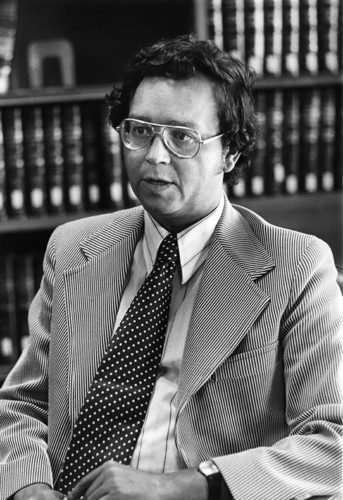

Gould was a visiting professor at Harvard Law School in the fall of 1971 when he was courted by Stanford Law School. He found the Palo Alto campus welcoming and he was appointed to the Stanford Law faculty in 1972—becoming its first Black member (joining Barbara Babcock, the first woman on the faculty, that same year).

“Yes, Bill Gould was the first Black faculty member at Stanford Law School. And we should bemoan the reality that it took so long to break the all white (and all male) barriers,” says Thomas Ehrlich, who was dean of the Law School in 1972. “But it is more important to applaud Bill for the remarkable teacher, scholar, and public official he has been over the past half-century, and the many barriers he broke along the way in shaping our labor laws.”

Labor’s Successes and Failings

Gould’s early criticism of labor for holding back racial justice has been a throughline of his research—beginning with his earliest articles, including “Employment Security, Seniority and Race: The Role of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” Howard Law Journal 13 (1967); “Labor Arbitration of Grievances Involving Racial Discrimination,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 118 (November 1969); and “Black Power in the Unions: The Impact Upon Collective Bargaining Relationships,” Yale Law Journal 79 (November 1969).

Gould’s new book, For Labor to Build Upon, offers critical historical context as well as a wide-ranging overview of the state of labor in the U.S. today—particularly in view of the COVID-19 pandemic. One focus of Gould’s analysis is on the unorganized workers in gig jobs and contract employment—and how labor unions are failing those workers.

“You see more minorities in skilled trades positions and supervisory positions than was the case early in my career,” he says. “But outside the unionized area, the workers are even more exposed today to exploitation and vulnerability.”

“Gould suggests that this great time of troubles known as the global pandemic has provided many opportunities for rethinking how injustices toward workers contribute to a malfunctioning society,” says John Trumpbour (BA ’81), research director of the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School.

“Bill has been a real pioneer in labor law, connecting conditions of the workplace to the health of democracy and advocating for greater representation in unions of those on the fringes and in new areas of employment,” says Jenny Martinez, Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Dean of Stanford Law School. “And as we saw during the pandemic, government responded in a big way to the very jarring shutdown of work and life as we knew it—providing benefits to workers who had never received them before, including freelance performers, contract workers, and gig workers.”

After years of decline, Gould says, unions possess the potential to be on the upswing again. He cites an impressive statistic: The number of petitions filed before the National Labor Relations Board, the primary arbiter of union organizational disputes, has increased 57 percent in the past year. But he remains critical of the unions for not doing enough, adding that while labor unions look to the law to help workers, that law is subordinate to union initiatives.

“The primary reason for union growth is not the law, but the organizational resources used by the unions independent of the law,” he says. “Even before the National Labor Relations Act was passed, there was an uprising of workers during the Great Depression and a furthering of union strength during World War II. That was when unions were using more of their resources to organize the unorganized.”

“Gould faults the U.S. labor movement for putting so much emphasis on labor law reform and electing friendly politicians, rather than stepping up the urgency and resources for organizing workers,” says Trumpbour. “He produces an impressive case for showing why understanding of labor history and public policy from distant decades of the 20th century need to be mastered if U.S. democracy is to have any hope of transforming industrial relations and the world of work in our 21st century.”

Gould notes that companies have been successful in characterizing gig economy workers such as Uber drivers as independent contractors—undermining even the California Supreme Court and state legislation. “The Dynamex decision by the California court was very sympathetic to the plight of these workers, but the legislation still has not been enforced in part because of Proposition 22 and in part because of the legal war of attrition that the employers have successfully pursued against any adherence to the law,” says Gould.

And while new laws do have a role to play, Gould stresses unorganized workers need the resources to organize that only the unions can provide—and they can’t wait for the law to advocate for them.

Sports, Law, and Organizing Campus Players

On June 21, 2021, the U. S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) cannot bar relatively modest education related payments for expenses to student-athletes.

“Justice Kavanaugh focused in particular on the enormous pay inequities—of university presidents, athletic directors, coaches, and others who are getting paid millions, and the players, who are disproportionately African American and low income, and are getting virtually nothing,” Gould says. He then points to an opinion by Peter Ohr, the NLRB Chicago regional director, about the time and effort students put into their work as athletes—spending 40-60 hours a week on athletics alone—and the control that universities have over them. “This is an enormous scandal that is just now being recognized.”

The Court’s ruling, and other efforts such as California’s Fair Pay to Play Act—a first-in-the-nation legislation signed in 2019 to allow college student-athletes to profit from their name, image, and likeness—has inspired a wave of states to take similar action to empower student-athletes.

Gould devotes an entire section of For Labor to Build Upon to amateur athletes and the fight by many to unionize and receive a piece of the multimillion-dollar pie that is college sports, but his interest in sports is not merely professional. He’s an avid baseball fan and, while he never made it to the pros, played seriously in his youth.

Gould is a prominent arbitrator with a depth of experience mediating disputes, including the 1992 and 1993 salary negotiations between the Major League Baseball Players Association and the Major League Baseball Player Relations Committee. He chronicled those experiences in Labored Relations: Law, Politics and the NLRB—A Memoir, which explores his time as NLRB chair and the drama surrounding it, including the baseball strike, and in Bargaining with Baseball, about his lifelong passion for the sport. Much earlier, Gould’s interest in sports led him to establish the field of sports law, writing one of the first papers on the subject “A Long Deep Drive to Collective Bargaining: of Players, Owners, Brawls, and Strikes” (Case Western Law Review, 1981), with his former Wayne State colleague Bob Berry, who went on to teach at Boston College. And while Berry’s was the first sports law seminar in the country, Gould’s soon followed, informed by his areas of expertise. “My materials were more focused on labor, arbitration, and antitrust, which became very important in labor disputes involving sports,” he says.

Hannah Gordon, JD ’08, chief legal and administrative officer for the San Francisco 49ers, took Gould’s seminar as an aspiring sports attorney. “Professor Gould made sure we learned the labor and antitrust history of sports. I kept with me that sports is an industry that touches all practice areas,” she says.

Gould brought serious star power to his seminar, started in the early 1980s, by enlisting former Golden State Warriors player and coach Alvin Attles and famed sportswriter Leonard Koppett as co-instructors—along with a deep bench of guest speakers that included Willie Mays.

“I was in awe when Dusty Baker came in to speak to us for the first class,” Gordon recalls. “I still can’t believe I was taught by Al Attles, NBA great and the second African American head coach in the history of the NBA, as well as former Golden State Warriors GM,” she continues. “Professor Gould also brought in legendary sports agent Bill Duffy, whom I continue to admire to this day. To Professor Gould, they were his friends and so they treated us with kindness.”

It may be Gould’s professional expertise that keeps him in the news and a sought-after speaker, but what stands out most is his passion for the fields he has studied, written about, and helped transform.

“Professor Gould’s passion was infectious,” says Gordon. “The greatest lesson was unspoken and learned by example: Do work that you are passionate about and enjoy the people you get to work with.”

And Gould is as busy as ever, speaking out on issues that matter to him and writing—including three op-eds in just the last few months and a memoir that he hopes to publish next year. He’s also teaching sports and labor law, reporting that the topics are once again popular.

When asked about the current state of American politics and challenges facing the labor movement, he harkens back to a book that he is particularly proud of: Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor. Published in 2002, it was a labor of love for Gould that he took up after the discovery of his great-grandfather’s original diary that chronicles the first William B. Gould’s escape from slavery and service in the U.S. Navy.

“My goodness, when we see that the Supreme Court has before it in the year 2022 a case involving the question of whether a state legislature may unilaterally establish all the rules relating to an electoral process, we know that this is a fragile time. But I think that the answer for young people and the answer for us all is, as William B. Gould did in the 1860s, to put one’s shoulder to the wheel and try to move this society in the best direction possible,” says Gould. “I feel I’ve been very lucky in life, and I feel that these students who are extraordinarily capable and sometimes confident have been lucky in life. To those whom much opportunity is given, much is expected. We have to try to make the best of this very uncertain time that we live in and move our society forward. I think we can, as we did in the 1860s and the 1930s, do that.” SL