The FDA Wants To Regulate Edited Animal Genes As Drugs

Summary

It’s 2017, and nothing means anything anymore. The latest logic-twisting development comes from the FDA, which last week released a draft rule saying it would like to treat any edited animal DNA as though it were a drug.

Or, more formally, as though it were some new type of pharmaceutical. Yes, yes, the FDA knows that edited DNA isn’t the same thing as drugs. But to them, edited DNA does the same thing as drugs: It changes the way bodies work. The proposal—which the agency won’t finalize until April, after reviewing months of public comments—is the latest clarification to a Reagan-era regulatory quilt that governs genetic alterations. And while not every geneticist is thrilled to have the feds throwing yield signs along their path, the regulations may actually make it easier for them to play with life—by making it easier for the public to trust the science.

…

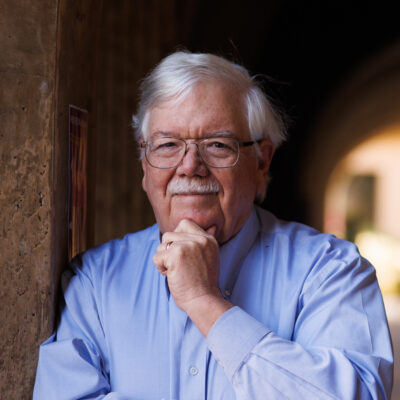

All this confusion isn’t just gene editing catching the federal government off guard. Back in the early 1980s, after scientists raised the alarm about the potential danger of recombinant DNA, the Reagan administration split jurisdiction over genetic alterations between three agencies. “The USDA, the FDA, and the EPA all had existing laws that worked for regulating the different bits and pieces of genetic engineering,” says Hank Greely, a genetics expert at Stanford Law. The USDA got to deal with crops, the EPA with anything that counted as a pesticide, and the FDA was left with any animals that might be used as food or medicine. The FDA needed these new rules, because those earlier ones only addressed transgenics—not gene editing specifically. In the past few years, new fast-acting gene editing methods like Crispr exposed some holes in the regulatory framework. “What the FDA is trying to do is fill in some of those holes,” says Greely.

…

Those accelerated outcomes are just one reason the FDA is proposing these new rules. There’s no guarantee that any edits won’t be off-target, or result in some unexpected mutation. Or, out of control natural selection—modified animals might ruin entire ecosystems. And then there’s optics. “The fact that everything we eat has had its genes modified over thousands of years by our ancestors seems to bother people a lot less than thinking about people in lab coats doing the same thing,” says Greely. He and Church both said they welcome the new regulations, partly because of the way they might reduce public backlash towards gene editing.

That public trust will be well-earned, because gene therapists are going to have to convince regulators their lab-made mutants are neither harmful nor useless. “This brings up three completely different classes of safety,” says Greely. “Safety for the animals having their genes modified, safety for humans consuming the animals, and safety for the ecosystem.” The FDA has experience with animal and food safety, but is basically clueless on environmental harm. In the draft regulation, the agency indicated that it might require gene hackers to complete environmental impact statements.

Read More