The fMRI Brain Scan: A Better Lie Detector?

Summary

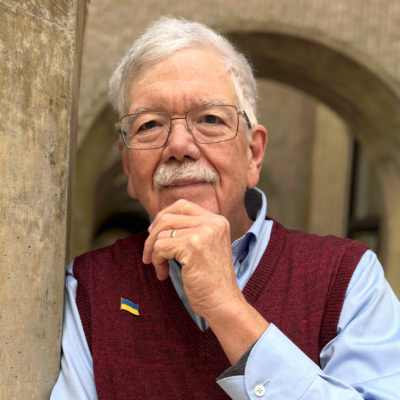

Professor Henry T. “Hank” Greely is quoted in this Time magazine story about the use, ethics, and efficacy of functional-magnetic-resonance-imaging (fMRI) technology for lie detection:

It would seem that being honest is an absolute, undebatable state. A person is either truthful or he’s not. Right?

Consider this scenario: a shopkeeper mistakenly returns an extra $10 in change to a customer. In one outcome, the customer returns the money promptly, without pause. In another, he hesitates for just a second, thinks about pocketing the 10 bucks, then decides to give it back.

Which is true honesty?

That is the question that Joshua Greene, 35, an assistant professor of psychology at Harvard University is trying to answer. More specifically, Greene is trying to identify the particular pattern of brain activity that distinguishes people who are simply telling the truth from those who are resisting the temptation to lie. His findings, which are based on functional-magnetic-resonance-imaging (fMRI) data, shed light not only on the workings of the human mind but also on the controversy over using fMRI technology outside the lab in the detection of lies. (Check out a story about how to spot a liar.)

In a cleverly designed experiment, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Greene recruited 35 volunteers and told them they would be participating in a study to find out whether people are good at predicting the future when they are paid for it. The real purpose, of course, was to get people to lie without asking them to lie — and image their brains committing an act of deception.

It is unclear what purpose reports from No Lie MRI or similar companies serve in such cases, since they have not been found reliable enough to be used in court. In March, an attorney for the defendant in a San Diego child-custody case attempted to introduce a polygraph test and a report from No Lie MRI to prove his client’s innocence. It might have been the first time fMRI lie detection was allowed in a court proceeding, had the county prosecutor’s office not objected to it and sought the assistance of Hank Greely, director of the Stanford Center for Law and the Biosciences.

…

It is unlikely that No Lie MRI will give up anytime soon — the company claims that the potential market for its technology could exceed $3.6 billion. While that figure seems exaggerated given legal safeguards against using polygraphs, Greely estimates that if fMRI lie detection became admissible in court, the industry could easily be worth more than a billion dollars per year. (See pictures from a wildlife forensics lab.)

“It’s a big country, there are lots of judges out there and I think they are hoping to find one who will allow the evidence, particularly if the other side doesn’t know much,” says Greely. “To be able to use [fMRI lie detection] in court would be the blue ribbon, the license to print money.”

Read More