Civil Rights in a New Light

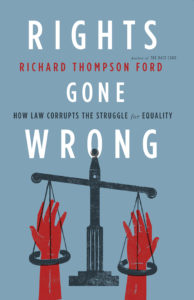

Richard Thompson Ford’s opinion piece in The New York Times last fall was something of a cat among the pigeons. In the essay, based on his book Rights Gone Wrong: How Law Corrupts the Struggle for Equality, Ford suggested that civil rights litigation was hurting the cause.

“But civil rights have barely made a dent in today’s most severe and persistent social injustices, such as the disproportionate incarceration of African-Americans, the glass ceiling that blocks career advancement for many women, and high unemployment among the elderly; in fact, some of these problems have gotten worse despite civil rights laws intended to address them,” wrote Ford (BA ’88), George E. Osborne Professor of Law, in the October 27, 2011, piece. “Today’s most pressing injustices require comprehensive changes in the practices of the police, schools, and employers—not simply responses to individual injuries.”

Civil rights leaders were quick to respond. The president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund wrote, “Although Mr. Ford rightly addresses the importance of tackling racial inequality, he articulates an artificially narrow view of the possibilities of civil rights litigation,” and the executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights weighed in with “To achieve civil rights goals, we do indeed need to look to new solutions, but it borders on the naïve to think that governments and police departments don’t still require more stick than carrot to get there.”

Clearly, Ford had struck a nerve. But he was merely doing something he has done consistently since joining the Stanford Law faculty in 1994—challenging us to delve deeper in our analysis of race and civil rights in order to move forward. A quick tick through some of his recent books illustrates the point.

“This book will shake things up …,” said Harvard University’s Janet Halley about Ford’s Racial Culture: A Critique, 2005. “[Ford] takes dead aim at racial opportunists, opponents of affirmative action, multiculturalists, and the myriad rights organizations trying to hitch a ride on the successes of the black civil rights movement. All, in different ways, he argues, are playing the race card. All are harming the cause of civil rights,” wrote William Grimes in The New York Times review of The Race Card, 2008. According to Jeffrey Rosen in The New York Times review of Rights Gone Wrong, 2011, “Ford does not offer an equivocal, cautious, middle-of-the-road critique of civil rights law. His book is sharp and surprising and casts the discrimination debate in a clarifying new light.” —And in Universal Rights Down to Earth, also 2011, Ford continues to cajole readers to break out of their comfort zones when thinking about rights, in this case human rights broadly—even if they find it uncomfortable to do so.

Ford’s scholarship is aimed quite deliberately at a wide audience, and in addition to books, he also writes regularly for Slate and has appeared on popular television and radio programs such as The Colbert Report and Dylan Ratigan. “I want to take these debates beyond the legal academy and make them accessible to a broader public,” he says. Though the initial impetus for Rights Gone Wrong, his most recent book, was very much anchored in the legal academy.

“I’ve been thinking about these issues for quite a while, but I suppose the spark for Rights Gone Wrong goes way back to a debate in the 1980s involving critical legal studies and a group that later became known as critical race theorists,” says Ford. “Several insightful studies, Mark Kelman’s book Jumping the Queue, for example, revealed the unintended consequences of well-meaning legislation.”

Another reason for writing Rights Gone Wrong, which was selected as one of the “100 Notable Books for 2011” by The New York Times Sunday Book Review, was simple frustration. “We’re not making the kind of progress I’d like to see. It has been more than 50 years since Brown v. Board of Education and in fact schools are not desegregated,” he says. “The courts have been a very unreliable vehicle for advancing social justice. That’s certainly not to say that there’s no discrimination and that we should repeal civil rights laws. But we should be careful about what is best understood as discrimination and a civil rights issue and what’s not.”

To press the point, Ford notes the uneven application of laws. “When faced with a social injustice, the first thing we do is cast around for discrimination complaints. And as the number of categories of unlawful discrimination expands, they are much more likely to be found. But this is an extremely costly way to deal with a pervasive problem. And it’s also uneven. So, how can we think about a more robust vehicle for social change—but one that isn’t susceptible to judicial backlash and judicial reinterpretation?”

Ford rejects the premise of some of the criticism of Rights Gone Wrong: “Most people agree with the proposition that civil rights have hit a wall, but we can disagree about why. A typical reason given is that it’s a conservative political climate with conservative judges. But that’s only part of the explanation.”

Along with targeting a wider audience for his scholarship, Ford would also like to see a greater focus on public opinion in the civil rights debate.

“I worry that sometimes lawyers and advocates might imagine that winning a legal victory is winning the battle. But if you don’t bring along public opinion and if the public thinks ‘this is ridiculous’ rather than ‘this is just’—then you’ve lost the war.”