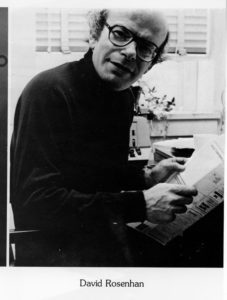

David L. Rosenhan, Professor of Law and Psychology, Emeritus

David L. Rosenhan, professor, emeritus, at Stanford University and leading expert on psychology and the law, died February 6, 2012, at Stanford University Hospital. He was 82 years old.

Professor of law and of psychology at Stanford since 1971, Rosenhan was a pioneer in the application of psychological methods to the practice of trial law process, including jury selection and jury consultation. He was the author of more than 80 books and research papers, including one of the most widely read studies in the field of psychology, “On Being Sane in Insane Places” (Science, 1973). He was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, former president of the American Psychological Association, former director of the American Psychology-Law Society, and former president of the American Board of Forensic Psychology.

Born in Jersey City, New Jersey, Rosenhan received a BA in mathematics (1951) from Yeshiva College and an MA in economics (1953) and PhD in psychology (1958) from Columbia University.

As part of his research for “On Being Sane in Insane Places,” Rosenhan and seven others had themselves admitted as patients to a total of 12 mental hospitals during a three-year period. They described hallucinations and “empty” feelings and were diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenics. As soon as they were admitted, they began acting normally and waited for the hospital staff to notice. The hospital staff never did notice, although many of the real patients caught on to the fakes.

Rosenhan wrote, “It is clear that we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals. … The consequences to patients hospitalized in such an environment—the powerlessness, depersonalization, segregation, mortification, and self-labeling—seem undoubtedly counter-therapeutic.”

Former psychology department colleague Professor Lee Ross recalls, “David was a spell-binding lecturer, and this famous study was as much an exercise in pedagogy as research. While it offered an important lesson about the failure of hospital staff (in contrast to the patients) to distinguish sane from insane behavior, a second lesson was no less important. That is, normal behavior—simply writing notes and going about one’s normal activity—when it occurred in the relevant institutional setting—was perceived by the staff to be a manifestation of mental illness. The lessons he cared most about offering, in his research and in the classroom, were most importantly ones about human dignity and the need to confront abuse of power and human frailties.”

At a time when legal scholars were just beginning to look to economics for insights into legal analysis, Rosenhan was among the first to draw from the social sciences, especially experimental psychology, to examine assumptions made by legal scholars in the trial process. Building on research on juror behavior undertaken by the University of Chicago Law School Jury Project in the 1950s, Rosenhan began to focus on other aspects of juror behavior. Among his interests was the jurors’ ability to abide by the judge’s instructions to disregard evidence the judge had ruled inadmissible.

Miguel A. Méndez, Adelbert H. Sweet Professor of Law, Emeritus, whose own work was influenced by Rosenhan, said that his former colleague played a key role in attracting students to the law school who were interested in the intersection of law and psychology and that he was known for his generosity, always making time to mentor young faculty and students.

Before joining the Stanford faculty, Rosenhan was on the faculty of Swarthmore, Princeton, Haverford, and the University of Pennsylvania and a visiting fellow or visiting professor at Oxford University, University of Western Australia, Tel Aviv University, and Georgetown University.

Rosenhan is survived by his son Jack Rosenhan of Palo Alto and his beloved granddaughters Cecily and Yael, as well as his brother Hershel of Jerusalem. SL