Health and Law

When Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg took a stand on sugary drinks, banning large sizes to encourage moderation, his efforts were met with some applause—but also with jeers of derision, one New York Post headline dubbing him the “Soda Jerk.”

But with one third of the nation’s adult population considered obese, and alarming evidence about the health dangers and economic toll of obesity, research on ways to slim America’s collective waistband is sorely needed.

Stepping back from the frenzy, faculty and students at Stanford Law School are digging into the issue to try to tease out the data and offer an unbiased empirical view.

Last spring, Jordan Flanders, JD ’15, worked with Michelle Mello (BA ’93) and David Studdert, two members of Stanford Law’s health law faculty, on a research paper that analyzed legal, economic, and political issues raised by sugary drink laws in different countries, explaining five major categories of regulations (taxes, government procurement regulations, school-based regulations, advertising restrictions, and labeling rules) and parsing out the biggest challenges to implementing each. The result, “Searching for Public Health Law’s Sweet Spot: The Regulation of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages,” was published in July in PLoS Medicine, a highly regarded international medical journal, and went a long way to inform the debate.

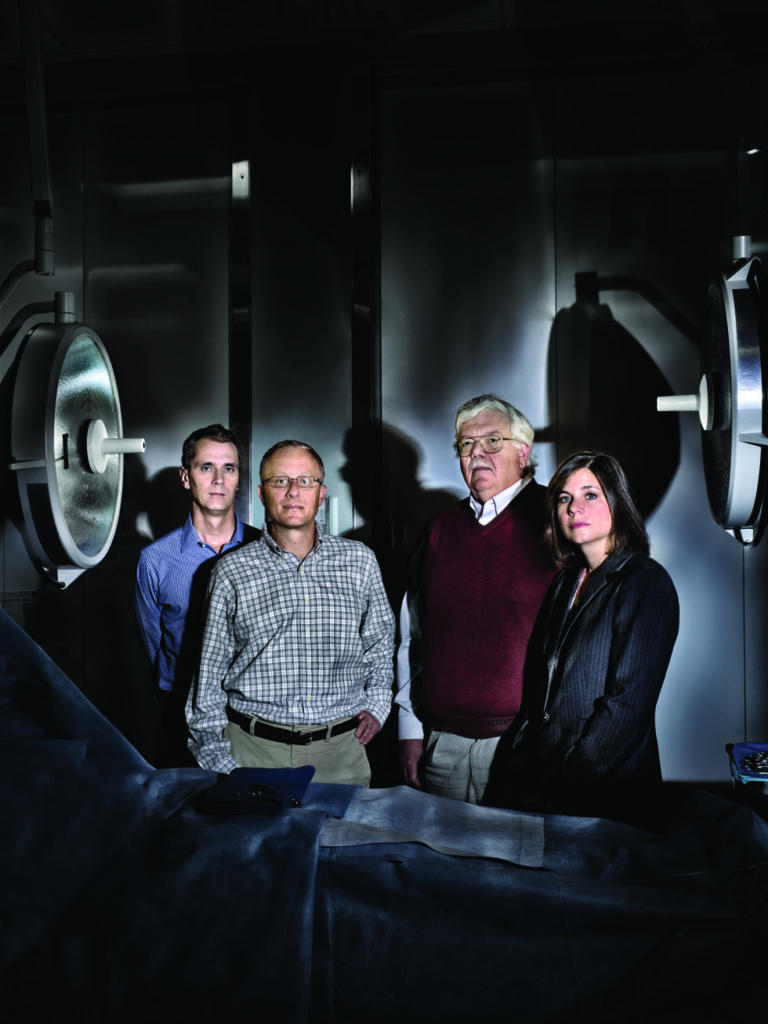

Stanford has taken the need for lawyers working in the critical area of health law seriously. Mello and Studdert, both professors of law with joint appointments with the medical school, were hired in the last two years. They joined Hank Greely, Deane F. and Kate Edelman Johnson Professor of Law, and Daniel Kessler, professor of law—increasing to four the number of faculty who are fully focused on health law. They are joined by half a dozen law faculty whose scholarship often touches on diverse subjects such as psychology, drug regulation, and environmental issues at this intersection of law.

Douglas Owens, MD, director of the Center for Health Policy at Stanford, helped spearhead the joint appointments of Studdert and Mello. “We were able to get two of the best people in the country, which enables us to meet our goal of working more closely with the law school.” The result, he notes, has proved to be “just fantastic,” adding “a whole new dimension” to the students’ experience. “It’s a story that’s just unfolding.”

Greely says that doubling the number of health law faculty “injected energy and expertise” into the program. The core professors meet monthly to coordinate their classes, collaborate on scholarship, and discuss ways to further deepen the student experience.

“What’s pleasing about this team is that we each have different areas of focus so the group covers the whole waterfront,” says Studdert, another dually trained scholar with a doctoral degree in health policy. “It’s a terrific convergence of scholars and a very exciting one for our students.”

“We have assembled, in just a few short years, a world-class team of researchers and teachers addressing the key issues of health care financing and quality, public health, and medical ethics,” says M. Elizabeth Magill, Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Dean. “In the years ahead, I am certain that our faculty and students will shape our understanding of these vital topics.”

Once considered a niche area of legal practice, health law has grown dramatically in both depth and breadth. Health care comprises more than one sixth of the country’s economy and the 2010 Affordable Care Act raised a host of new health law issues. Adding to the new terrain for American health care are deep questions about the proper role of government in protecting and promoting health. “Public health law has been around for a long time, but historically its focus has been on infectious diseases, environmental toxins, and, more recently, injury prevention,” Mello explains. “But today’s big health juggernauts are different. Non-communicable diseases—cancer, heart disease, lung disease, diabetes—these are the big killers in the U.S. And public health law is a relative stranger to these health threats.”

“That’s the way that health law and policy are going—everything gets more complicated,” says Kessler, JD ’93, who also holds a PhD in economics. His book Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: Five Steps to a Better Health Care System outlines how market-based health care reform in the U.S. can help fix current problems.

Studying the big questions at the center of health and law is as interesting as it is important, faculty employing different methods to study these questions. “Our professors don’t just write about the law,” says Kessler. He, for example, analyzes how tax policy affects medical spending. He also deconstructs so-called vertical integration: how primary care doctors, specialists, and hospitals work together to address a patient’s needs, a trend accelerated by the Affordable Care Act. Similarly, Mello and Studdert have used data analysis to examine medical malpractice and patient safety. In particular, they have studied the rise of “defensive medicine,” in which physicians order tests and procedures to reduce liability.

Stanford is an ideal setting for this group’s work too. Stanford Law School sits a stone’s throw from one of the nation’s top medical schools, Stanford School of Medicine, as well as within a major hub of industry. “We’re in Silicon Valley, but this is also ‘Life Sciences Valley,’ ” says Greely (BA ’74). “There are world-class companies stretching from UC Berkeley through UCSF down to Stanford and beyond, offering great opportunities to maximize industry and scholarly partnerships.”

That kind of collaboration matters because scholars are working to solve very real policy challenges at the crossroads of law and health. By producing research that addresses pressing questions, these health law professors have the potential to shape public policy and improve the population’s well-being. “We’re trying to produce evidence that can influence judges and policymakers,” Mello explains. Mello, for instance, is collecting public opinion data to determine whether attitudes toward laws that restrict individual liberty in order to curb non-communicable diseases become more accepted after the initial implementation period.

Another example is a recent law school Policy Lab co-taught by Owens (BS ’78, MS ’91), former SLS Dean Paul Brest, and Deborah L. Rhode, Ernest W. McFarland Professor of Law, in which medical and law students together examined how policy could stem the childhood obesity epidemic. Santa Clara County Supervisor Ken Yeager was so interested in the lab’s work that students concluded the course by presenting position papers to him.

“The Policy Lab was actually a learning experience for me too,” Owens adds. “It demonstrated the importance of law in health policy and how local elected officials can make things happen. It was a very direct route of work translated into action.”

Health law is an exceptionally interdisciplinary field, drawing on law, political science, medicine, economics, ethics, social psychology, organizational behavior, finance, and more.

“You can’t study health law in isolation from economics, finance, or clinical work,” says Kessler.

That interdisciplinary emphasis is what drew Maggie Thompson, JD ’16 (BA ’10), to the law school. She studied human biology as an undergraduate and conducted research on child development. “I really valued the opportunity to work at the intersection of science and social science to solve complex social problems at law school.” In her second year, Thompson worked with Studdert and Kavitha Ramchandran, MD (BA ’99), an oncologist and palliative care physician, on a study that examined the legal needs of patients with life-threatening illnesses at Stanford Hospital.

“Lawyers and health care providers are increasingly recognizing the need for integrated medical-legal care,” explains Thompson. “Nonetheless, the legal needs of people suffering from serious illnesses continue to go unmet, which negatively impacts the quality of life and care for patients and their families.” To that end, Thompson helped develop Stanford Hospital’s own needs-assessment questionnaire. “The hope is that eventually we’ll be able to give the questionnaire to more patients, with the long-term goal of developing a partnership between the law and medical schools to address patients’ concerns.”

Flanders took a class at the medical school called Social Determinants of Health, which was taught by a pediatrician. “I loved learning about public health challenges from a practical point of view,” says Flanders, whose interest in health law was sparked by a seminar she took in her first year called Medical-Legal Issues in Children’s Health, co-taught by a doctor and a legal aid lawyer. The founder of SLS’s Food Law and Policy Society, Flanders joined a San Francisco firm this fall, where she’s working on health inequities. “My passion for public health was not fully developed before I arrived at Stanford so I credit the wonderful professors and especially the strong connection between the medical school and the law school. Each class I took exposed me to more opportunities to fine-tune my focus.”

Reece Trevor, JD ’17, took Mello’s Health Law: Improving Public Health while still a 1L to prepare for his summer internship at a public health law nonprofit, ChangeLab Solutions in Oakland. He has a long-standing interest in food policy and was glad that the class had a significant emphasis on that topic. “It was remarkable how so much of what I did in the class touched exactly on what I did during the internship. My biggest project at ChangeLab involved First Amendment constraints restricting healthy school food. I would have been miserably unprepared if not for the class,” says Trevor.

The health law faculty also aims to be a timely source of information on health care issues. Mello and Studdert commented on California’s tough new vaccination requirements in a New England Journal of Medicine article soon after the law was passed. And within a day of the King v. Burwell case that upheld the Affordable Care Act insurance subsidies, several law faculty blogged about the implications of the Supreme Court’s decision. Greely’s post addressed the strength of the majority’s arguments and what the case meant for the future of American health care.

This timely, empirically informed scholarship and opinion have great value for policymakers. Jeff Wu, JD/MBA ’01, is the acting deputy and policy director at the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, a division of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “We are what I think of as the Obamacare agency. We’re in charge of private health insurance reforms under Obamacare, including the exchanges,” explains Wu, who leads the group’s policy and regulatory work and handles press and stakeholder communications. “My agency has to make difficult trade-offs with limited information as we set policy,” he says. “I’m always eager to have our policy informed by solid, cutting-edge empirical research, and I’m looking forward to reviewing the research coming out of SLS.”

Sean Johnston, JD ’89, senior vice president and general counsel at Genentech, says he and his 100-lawyer department “certainly pay attention to the scholarship at the law school—and the university more generally,” including attending health law conferences. “The issues are so complex and often so interdisciplinary; the law school’s approach of gathering scholarship from other areas like medicine, business, and economics is very important. It’s really what will yield the most worthwhile insights,” says Johnston, who earned a PhD in molecular biology and worked for several years as a scientist before attending Stanford Law.

Greely, who joined the faculty in 1985, was the law school’s only health law professor for 20 years and remains the law school’s FDA expert. Today, he also studies legal and social issues that arise from advances in life sciences, like genetics, neuroscience, and assisted reproduction, directing both Stanford Law’s Center for Law and the Biosciences and the newly launched Stanford Program in Neuroscience and Society (SPINS), among other university programs. He recently completed the manuscript of a book, The End of Sex, which suggests that in just a few decades the majority of babies will be conceived via IVF so that parents can first check genomes and decide which embryos to implant.

In the past three decades, more and more students with health or science backgrounds have enrolled at SLS, Greely observes. Now, as many as 15 to 20 students out of an entering class of 180 have a background or interest in health law. Some were pre-med undergrads; some were biosciences PhDs. Others grew interested in health care after working in management consulting or at health-related nonprofit organizations.

Greely noticed an especially big shift in the program when the law school switched from the semester to the quarter system. “It got us out of sync with other law schools, but got us in sync with the rest of Stanford,” he explains.

Even before the switch to the quarter system, though, health law at Stanford benefited from a willingness of faculty members outside of the law school to collaborate with SLS faculty and students. “Our colleagues in other professional schools—say, an expert in neuroscience—are a five-minute bike ride away and they’re happy to talk.”

Meanwhile, more and more medical students and PhD students in medicine, engineering, psychology, political science, and philosophy are enrolling in SLS’s health law classes. “It has increased my enjoyment,” Greely says. “They offer me and the law students new and diverse perspectives. Our discussions are broader and more interesting.”

Exactly those kinds of “inter-professional” experiences are supremely valuable to law students, says William Sage, who received medical and law degrees from Stanford in 1988 and is now on the faculty at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law. “Stanford’s early efforts to normalize interdisciplinary studies gave me a chance to build a career I would never otherwise have considered,” Sage notes, adding that the program has come a long way since he was a student. “When law students work collaboratively with medical and business students, patients benefit, through programs like medical-legal partnerships, and society benefits when students and practitioners from different disciplines develop innovative technologies and new ways of delivering care.”

Amanda Rubin, JD ’16 (PhD ’18, neuroscience), has been co-president of both the BioLaw and Health Policy Society and SIGNAL, the Stanford Interdisciplinary Group in Neuroscience and Law, so she has spent many hours organizing intellectual “mixers” for graduate students across campus. And she has been impressed by the mutual interest law students and science students have for each other’s fields of study. “This place is such a melting pot,” she observes.

Rubin decided to pursue a joint degree because “there weren’t a lot of people who could speak both languages—science and law. I wanted to be one of them.” And while joint degrees are increasingly prevalent at Stanford Law, she appreciates efforts, like SIGNAL, to encourage non-joint degree students to explore fields outside of their area of study. “I think there are more and more students who, though not pursuing joint degrees, have an interest in health law. The questions in this field are compelling too: life, death, disease, etc.,” she says. “The programs and courses offered at Stanford are great for people who are interested but can’t spend as much time as I am learning about both sides of the fence. Not everyone can take on a PhD program on top of law.”

Her motivation for pursuing such a demanding graduate program came during the summer after completing her undergraduate studies (in molecular biology) while working for the Washington, D.C.-based American Association for the Advancement of Sciences. After attending a particularly long Senate hearing, Rubin decided she needed to go to law school. “The senators clearly did not understand the science and the hearing dissolved into a conversation devoid of fact,” she says. “I realized that scientists sometimes mistakenly believe that it’s enough to do great research—‘if they build it, they will come.’ But I don’t think that’s true. We need lawyers who understand the science.”

Health law faculty also adjust the way in which they teach to welcome non-law students. Trevor was struck by the composition of Mello’s class, Health Law: Improving Public Health, which was about 60 percent law students and 40 percent medical students. “It had a dramatically different character compared with a core law course,” he says. “Professor Mello did a good job of bringing those perspectives together—the lawyers wanting to point out risks and say no, and the doctors wanting to say yes!”

Kessler’s course, Health Law: Finance and Insurance, which he co-teaches with the School of Medicine’s Kate Bundorf, includes medical and business school students in addition to law students. So they ditched the Socratic method. Instead, everyone discusses articles from such publications as The New England Journal of Medicine and Oregon Law Review, as well as health-related news stories from The New Yorker, The Washington Post, and The Atlantic. “The approach engages everybody across many disciplines,” Kessler explains.

Similarly, in David Studdert’s Regulating the Quality and Safety of Health Care course last spring, medical students comprised a third of the class. “Our work is so interdisciplinary that we don’t even really think about it—it’s just baked into the questions we’re interested in,” Studdert says. “I’ve received many comments from law students saying how wonderful it was to get the perspective of medical students. Taking classes together exposes them all to a new way of thinking about health issues. Our law students very quickly find their way to the key questions. The medical students, who have already started seeing patients, bring us back to the bedside and help us understand how the rules we’re talking about may be unworkable or may disadvantage some patients. Can you imagine a better reality check than that?”

And Stanford Law is aiming to train its students in the complexities of health-related industries and their legal issues. Driven by the growth and aging of the population, the increasing government and societal focus on health care delivery, as well as an explosion of technologies that diagnose and treat disease, health care is an “increasingly prominent part of our society,” says Genentech’s Johnston. “A health care business is inherently complicated. In-house lawyers are called upon to provide comprehensive legal advice to our business, everything from food and drug law to intellectual property to insurance to Medicare. Lawyers are required to bring together all these different disciplines.”

Careers for students who’ve studied health law are as diverse as the scholarly interests of the faculty. They can be found at law firms, in government, and in-house at health care, life sciences, pharmaceutical, biotech, and insurance companies. Some alumni do policy work at state or federal agencies, for example, at the FDA, Medicaid/Medicare, or at an attorney general’s office. Still others work at nonprofits, advocacy groups or, like Sage, in academia. Rubin spent her 1L summer working at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, where she worked on antibiotic resistance and an initiative to map the brain. During her 2L summer, she worked for Google X’s life sciences division, tucking into interesting work on contact lenses to measure glucose levels and the like.

Wu began his career in the corporate group at a law firm with a strong FDA practice. He spent years representing pharmaceutical companies in large transactions before moving to the Obamacare agency. He has seen firsthand how critically important health law is—the scholarship and the practice—to individuals and the country as a whole.

“This is an area of law that is changing in fundamental and important ways every day,” says Wu. “Scientific advances, commercial trends, and regulatory, statutory, and occasionally constitutional changes are creating difficult legal, policy, and moral issues. Tackling these issues is going to require the kinds of lawyers that SLS routinely produces: smart, creative lawyers that can cross lines between legal areas and between disciplines, including public health and policy, genetics and economics.” SL

Leslie A. Gordon is an attorney and legal affairs journalist.