Legal Education in Afghanistan

Afghanistan is an unlikely classroom for Stanford Law School students. In the grip of war since 2001—the second major foreign military intervention in 30 years—it is a country struggling to find its way to peace and stability. Essential to these aims is the development of the rule of law. But it is a nation of the young—where the median age is just 18 and the people are yearning for education. As more students aspire to attain a university degree, many eager to participate in rebuilding their country, a group of Stanford Law students is helping to meet the challenge of establishing legal education in this fledgling democracy.

Rose Ehler and Daniel Lewis returned from a trip to Kabul in February—both are 2Ls and midway through their term as co-executive directors of Stanford’s Afghanistan Legal Education Project (ALEP), leading the fifth student management team since the project launched in 2007.

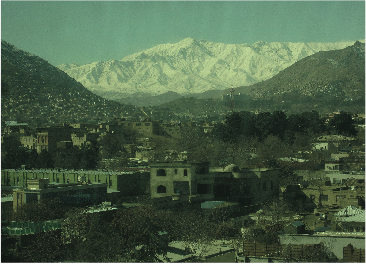

Lewis recalls a sign at Kabul airport, “Welcome to the land of the brave,” which greets guests and cautions them as well. “But Kabul is really another world,” he says. “It’s a bustling city, with beat-up shanties, partially destroyed buildings, and strip malls. War torn but also booming. And then you see the beautiful mountains surrounding it.”

The trip was a culmination of months of hard work for the Stanford Law students on the ALEP leadership team who made the journey this year—likewise for the students who traveled there before them. For those involved at the launch of ALEP, dealing with legal curricula that predated such developments as the 2004 constitution and coping with the severe shortage of printed texts were paramount.

But legal education in Afghanistan has come a long way in four short years, and ALEP has made a significant contribution to that progress. At ALEP’s inception, the group partnered with the American university of Afghanistan (AUAF)—forming a union that has been instrumental to the success of both. When it was opened in 2006, the Kabul-based AUAF was a new venture with no legal program. ALEP founders, Alexander Benard ’08 and Eli Sugarman ’09, approached Stanford Vice president and general counsel Debra Zumwalt ’79, an AUAF board member, and suggested that they help develop one. Zumwalt, in turn, told them they needed the support of a faculty advisor to take on the task. The students took the idea to Erik Jensen, co- director of Stanford Law’s Rule of Law program, and to Larry Kramer, Richard E. Lang professor of Law and dean. And ALEP was born. Since that time, approximately 330 Afghan students have completed courses designed by ALEP in conjunction with AUAF.

ALEP’s mission is somewhat audacious: the development of innovative legal curricula to help Afghanistan’s universities train the next generation of lawyers and leaders. But this is a dedicated group. Ehler and Lewis put in some four to six hours each week managing the project—fielding calls from any number of people interested in what ALEP is doing, conducting telephone interviews with potential teachers, and more. All this is in addition to researching and writing ALEP texts—and carrying a full Stanford Law course load.

“It’s like running a company,” says Ehler. “We have weekly meetings. Daniel and I delegate to our teammates, trusting that things will get done. There are a lot of different balls in the air at any one time—someone working on translation or on military outreach, others handling urgent e-mails or talking with the U.S. department of commerce.” The list goes on.

“I was just on the phone with two senior advisors from the department of commerce,” she says. “And I surprised myself at how authoritatively I speak about the project now.”

Then there’s managing the $1.3 million grant from the state department. It’s a job to make sure we’re reporting everything correctly,” says Lewis of the grant, which funds one of the five law faculty positions at AUAF, part of the Stanford Law faculty supervisor position, and expenses such as printing and travel.

“We’re beyond proof of concept,” says Jensen, the faculty advisor to ALEP’s revolving cast of students since the project launched. “There are always far more students interested in working with ALEP than the seven spaces allotted. I never could have imagined that we’d be able to build out the program as we have with high student demand, recruitment and retention in Afghanistan of the highest quality of faculty, an administration at the AUAF that is just so interested in making this an institutional priority, and tremendous support from our dean here.”

While the country’s constitution became the official law of the land when it was ratified, Islamic and tribal laws continue to play strong roles in the legal system. ALEP’s principal focus is researching, writing, and publishing high-quality, original legal textbooks that include an emphasis on the application of secular laws and how they might co-exist with local customs and religious rules.

“We are not engaging in legal imperialism,” says Jensen. “Local practice and culture are necessarily part of our view.”

To date, ALEP has published three textbooks, all in English, which are among the first to specifically address Afghanistan’s post-2004 legal system: An Introduction to the Law of Afghanistan (second edition and now available in Dari), Commercial Law of Afghanistan, and Criminal Law of Afghanistan. A fourth text, International Law of Afghanistan, is in its final stages, and a fifth, Constitutional Law of Afghanistan, will be available late 2011. All of ALEP’s publications are available online for free use and distribution. Additional Dari and Pashto translations are forthcoming.

Jensen, a senior research scholar at the Freeman Spogli institute for international studies, revels in his students’ successes.

“It’s a collaborative process between me and the students and, perhaps more importantly, among the students themselves,” says Jensen. “They have set very high standards and do not allow laggards.”

Certainly, the goals set forth by ALEP are challenging—even more so given that law students are doing much of the work. But law school and ALEP workloads overlap. And the students have a wealth of knowledge available to them in the guise of Stanford Law faculty, many of whom have consulted on the project, as well as faculty at AUAF and elsewhere in Afghanistan.

“At the beginning of each cycle of new students, I often hear ‘we don’t know anything, we can’t do this.’ Then there’s a shift in confidence about three months in when they realize that they know they can do it, they’re empowered to do it,” says Jensen. “These students spend so much time and energy researching and writing. They make sure that the texts they write are not boring. They aren’t trained in curriculum development or pedagogy, but they’ve been exposed to some of the best in the world. So they think about what might be interesting to them as they master an area for a text. They raise questions designed to spur lively debate. They do so much better than they think they can—certainly better than some of the extraordinarily well-compensated consultants in the international rule of law industry with whom I’ve worked could.”

The February trip was an opportunity to visit AUAF and Kabul University, to hear feedback on books and curriculum already in use, and to assess needs going forward. The team met with law faculty and senior members of the afghan government, including the chief justice, the deputy minister of justice, and a commissioner on human rights. One meeting with the dean of Kabul University ended with a request for 1,200 ALEP texts.

Equally important, though, were the meetings with students at AUAF.

“The young people do have a sense of optimism,” says Lewis. “There is a generational divide. They see what’s going on in the government and want to change it.”

“When you ask the students about why they take our classes, they say they want to understand what’s going wrong in Afghanistan. They know that corruption is a problem, and they’ve asked for a book on anticorruption,” says Ehler. “It all turns on their sense of obligation and ability to not succumb to corruption.”

“The textbooks are impacting this small group of university graduates, but they are the ones who will become the next generation of afghan leaders. So they’re learning about values, ethical behavior, and the rule of law. There’s a lot of talk about the next generation—and they are our students,” says Lewis.

“This is exactly what you want graduating law students to feel—the oats of their own potential to change society,” says Jensen. “The best we can do is give them these tools—knowledge, critical thinking, practical legal skills—to help them in that just cause.”

The ALEP curriculum is designed specifically to teach and develop critical thinking skills and to supplement the traditional doctrinal education that typifies legal education in Afghanistan—to “bring law down from the clouds,” says Jensen, so that students can understand the theory of law but also develop skills that they can use in their careers. Students are not only taught about the law but also how to think analytically. A core skill set is in critical thinking, logical thinking, logical argumentation, and logical writing—things that apply to all professional life. ALEP offers a substantive course load, according to Jensen, with a broad selection of foundational courses—from constitutional law, criminal law, and so on. And it focuses on leadership.

AUAF students who complete the current three-year legal studies curriculum receive a certificate in Legal studies—a key qualification for those pursuing a career in government.

Collaborating with afghan colleagues and seeking advice from educational and governmental influencers are key to the success of ALEP. So the team used their time in Kabul for face-to-face discussion about the prospects of further developing the legal curriculum at AUAF—taking it from a three-year certificate program for which students minor in law to a five-year accredited program with a major in law.

“Now we’re moving on to the next phase: developing a center of excellence in legal education. It will take some years, but that’s the goal,” says Jensen.

Essential to that is developing an understanding of the current state of the legal system in Afghanistan.

However, the work of ALEP is not done in a vacuum. Part of the group’s research involves understanding where their afghan students will work and matching the education that ALEP helps to shape with the needs of the country. There are traditional avenues for a legal career via government services and the judiciary. There are also opportunities within government ministries, as well as at international organizations—both governmental and nongovernmental. The legal market in Afghanistan is evolving, with the tradition of informal dispute resolution offering limited but growing opportunities for lawyers in the private sector. As the country’s drug trade makes way for other trade—and as education and civil society take hold—lawyers will be required and the law will play a greater role in society.

“Afghanistan has tremendous human resource needs across the board. And we know that a lot of lawyers become leaders—law is an incubator for leadership,” says Jensen. “Whether our graduates practice law, work in business, or work in the government, they will benefit from these courses, which enhance their understanding of the rule of law, good governance, and government function.”

“I met one student who is taking a night class at AUAF. He works at Afghan Radio, but much of what he reports on has to do with the law,” says Ehler.

“Another student, after taking the commercial law class, said his boss was like ‘here write this contract,’” adds Lewis.

“Our books are showing up everywhere—in the U.S. military, in the Afghan government, in law schools throughout Afghanistan. The attorney general had our law text on his website for a period of time,” says Jensen.

Lewis is deep into his current project: writing an introduction to a textbook on methods of interpretation of the constitution. He’s looking for the paper trail from the people who wrote the Afghan constitution in 2004. But the trail’s gone dry. “We asked one of our AUAF faculty to see if there’s an equivalent of our James Madison—we need the notes and letters from the 500 or so people who were there and who ratified the new constitution,” says Lewis. “We’ve heard that there are documents somewhere in Afghanistan—now we need to find them.”

The workload that Stanford students take on in ALEP is both fascinating and daunting, and Jensen acknowledges that the students “are working flat out.” But they don’t seem to mind.

“It’s a way to have one arm outside of the law school, to take the knowledge we gain here, bring it halfway around the world, and put it to immediate and good use,” says Ehler. “It’s rewarding.”

Pressure to expand the project is building to meet demands both in Afghanistan and from students at Stanford.

“This year was tough. We had a number of very well-qualified students who didn’t get into one of the three rule of law projects,” says Jensen. “But we like the small size of these groups—we become family. And the students like the intimacy of the group, the accountability that they hold each other to.”

That is one of the challenges of success that will be dealt with later. For now, the ALEP team is too busy moving ahead with the urgent work at hand.

Before rushing off to the airport for a flight to Bhutan, Jensen offers one last thought:

“This project has changed me in a way that I didn’t expect in the span of a twenty-five year career in the field of international rule of law. I’ve always thoroughly enjoyed teaching and interacting with Stanford Law students, who doesn’t? But when you see able and inquisitive students taught by able faculty in classes that you’ve worked on designing and resourcing, in a place like Afghanistan, it’s absolutely magical. It has taught me that I can be even more passionate about this work than I thought possible.” SL

Read about Stanford’s Rule of Law program in an accompanying article, “From Afghanistan to Bhutan to Timor-Leste,” here.