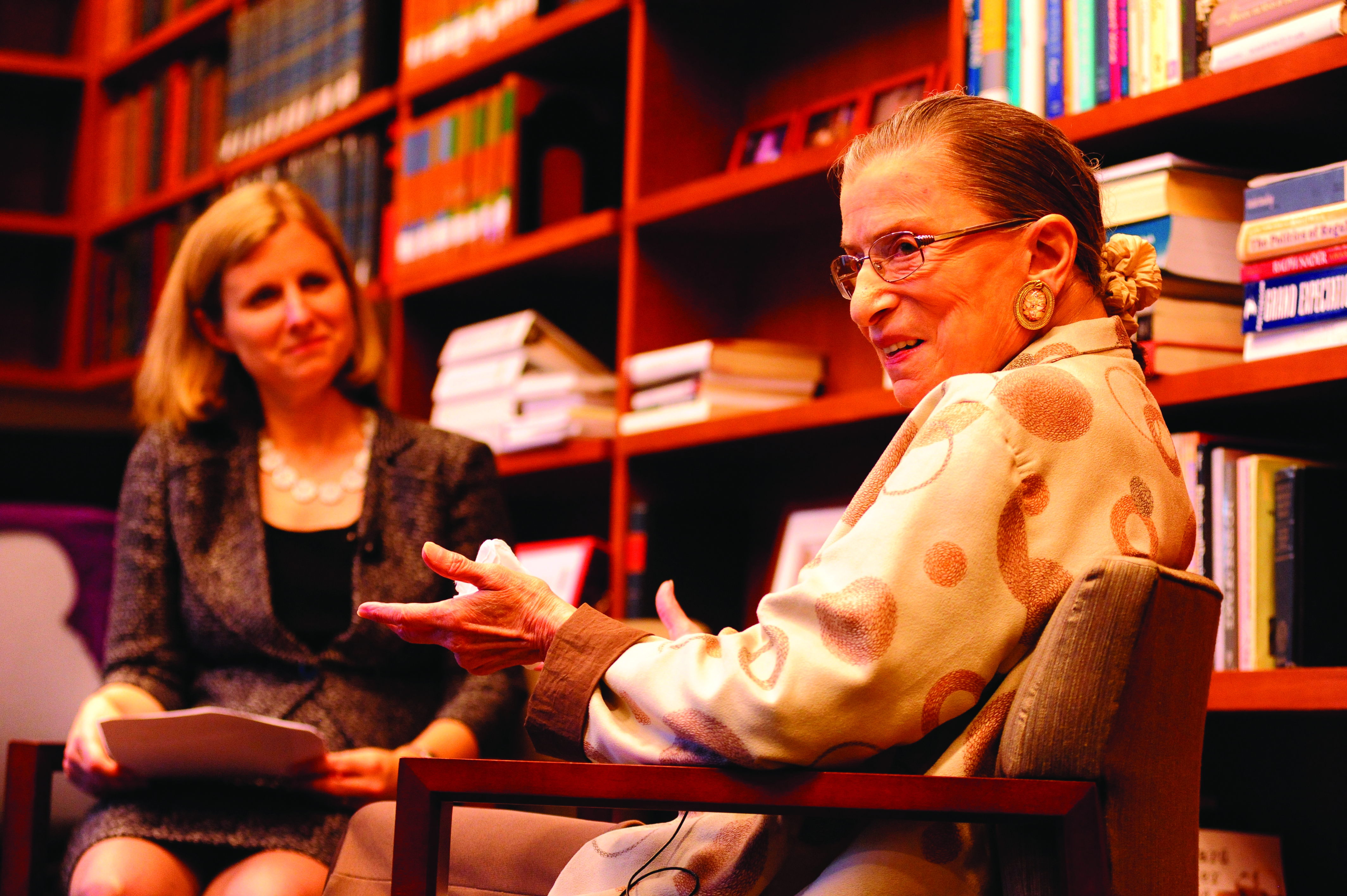

At the U.S. Supreme Court: A Conversation with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg visited Stanford Law School on Constitution Day to deliver the lecture, “Some Highlights of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2012-2013 Term.” The following is a version of Dean Magill’s introduction of Justice Ginsburg.

Justice Ginsburg was our guest at Stanford Law School in September, helping us celebrate the U.S. Constitution. It was fitting. Her life’s work has been to redeem, and to make good on, the full promise of the Constitution’s protections. As she has put it, our country has progressively worked to expand who counts as the “We” in “We the People,” and Justice Ginsburg has been a key architect of that expansion.

It is not really possible, in a short introduction, to capture the breadth of Justice Ginsburg’s contributions to this country. But I am going to try. I will do that by focusing on the people she has touched. Justice Ginsburg’s life work has directly affected the lives of at least three or four generations in this country.

You are probably thinking of Justice Ginsburg’s role as an associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, where she has sat for 20 years since President Clinton appointed her in 1993. Now among the senior justices, she often writes for the majority, or for the dissent, in important cases. But this is only a part of the story of her achievements.

Justice Ginsburg went to Harvard Law School in the late 1950s when there were almost no women. For women in the law, this was a generation of pioneers. The story of what she experienced may seem like ancient history, but it is not. She was a woman of formidable talents, and, yet, those talents were not recognized because of deeply embedded views about the appropriate roles and capacities of women. After two years at Harvard, she moved to New York with her husband and young daughter and finished her legal studies at Columbia Law School. Despite being a top student and a Law Review editor, she endured a less-than-welcoming environment in law school and a shocking lack of interest from future employers. When she was looking for a legal job, there were three strikes against her. As she has put it, she was “a Jew, a woman, and a mother—that was a bit much.” She was eventually offered a clerkship with Judge Edmund L. Palmieri of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, but only after her former teacher and mentor Professor Gerald Gunther, who chaired the Columbia Law School clerkship committee, twisted some arms.

The barriers she faced would have felled an ordinary person. But she is no ordinary person—she was the first in many places previously closed to women. She joined the academy in 1963, first teaching at Rutgers University School of Law. In 1972, she accepted a position at Columbia Law School and became its first tenured woman member of the faculty. She was a practicing attorney and passionate advocate for equal rights. She co-founded the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project in 1972. While serving as the project’s first director, she devised a winning strategy to challenge laws that distinguished between men and women. She targeted laws that treated husbands and wives differently for purposes of dependent care benefits; that treated widows and widowers differently for purposes of survivors’ benefits; that treated women differently from men for purposes of jury service.

These laws, Justice Ginsburg saw, burdened both men and women by embedding stereotypes about proper roles for each gender in the law, and they were barriers to women’s full citizenship. Her strategy in these cases sometimes featured men who were in caretaking roles and who were disadvantaged by laws that were built around assumptions about the proper roles of women and men in the family and in the public sphere.

The strategy was brilliant. She argued six cases in the Supreme Court, winning five. In the process, she established the modern law of equal protection as it relates to equality between the sexes. The first case she argued, the landmark case of Frontiero v. Richardson, was decided 40 years ago this year. In Frontiero, four members of the Supreme Court, for the first time, declared that laws that classified people based on their gender were “inherently” suspect under the Constitution. She went on to serve as the ACLU’s general counsel and on its National Board of Directors—and briefly even spent time here at Stanford as a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences from 1977 to 1978.

Justice Ginsburg transformed from scholar and advocate to judge when President Carter appointed her to the federal appellate court in the District of Columbia in 1980. Thirteen years later she was appointed to the Supreme Court.

She has now been a judge for 33 years. I cannot capture her nuanced jurisprudence, but let me focus you on one aspect of her decision making. Many of you know of her decisions about fundamental rights. She wrote the opinion for the Court striking down Virginia Military Institute’s all-male admission policy. She penned very well-known dissents in Bush v. Gore and the voting rights and affirmative action cases this last term.

Justice Ginsburg, however, is often described as a “judge’s judge.” She is engaged by matters of procedure and of jurisdiction, as much as she is engaged by matters of rights. Any list of her notable cases includes cases about who can bring suit, the proper shape of class actions, and the proper role of federal courts vis-à-vis state courts.

This is an approach to judging that one might connect to Justice Ginsburg’s experience as a legal advocate. She has deep commitments about the meaning and promise of the law, but she has a lawyer’s caution about bold pronouncements untethered from attention to institutional competence and getting the details right. As she once said, bold pronouncements can be unstable.

It may be that pragmatic, lawyerly realism is one reason that Justice Ginsburg’s life’s work will be lasting.

In her own generation, she was a pioneer, an example of what women were capable of doing in realms previously closed to them. And she was repeatedly victorious. Successive generations have experienced a different world because of her work. Women were no longer asked, as she had been, why they took the place of qualified men in graduate schools. Formal barriers to women’s advancement fell away and remarkably quickly they began to seem anachronistic, even to the generations that immediately followed her, including my own. I am personally grateful for all that she has done. I hope that the discussion that follows sheds light on this singularly gifted lawyer, scholar, and jurist.

– M. Elizabeth Magill, Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Dean

Magill I’d like to start by looking back to what prompted you to go to law school. Why did you have that ambition?

Ginsburg As an undergraduate at Cornell, I had a great professor named Robert E. Cushman. He taught constitutional law. And he wanted his students to understand that our country was straying from its most basic values. In my years at Cornell, Senator Joseph McCarthy held sway—a man who saw a Communist in every corner, including major university faculties. The House Un-American Activities Committee and Senate Internal Security Committee were calling people on the carpet, many of them leading lights in the entertainment industry. Cushman’s point was that lawyers were standing up for these people, reminding Congress that there was a First Amendment and a Fifth Amendment. The notion was that you could be a lawyer and aim at something outside yourself. You could help to repair tears in your community.

Still, my family had grave doubts about my going to law school, because women lawyers were not welcomed at the time by the Bar or the Bench. Could I make a living? Then, when I married Marty the same month I graduated from Cornell, my family thought law school would be okay for me. If I didn’t get a job, there would be a man to support me. So, marriage, far from hindering my legal career, advanced it.

Magill Can you talk a little about your law school career?

Ginsburg My law school class [at Harvard] had nine women out of a class of over 500. A big jump from Marty’s class—he was a year ahead of me and there were five women in his class. It was such a different world back then. So many things made no sense. For example, when I was at Cornell University, in the arts college, the ratio was four men to every woman. The reason why—women had to live in the dormitories, but men could live off campus in college town. Then I became a student at the Harvard Law School, where there were no rooms in the dormitories for women, instead women had to find places to live in town. It didn’t matter to me because I was married with a child by then. But such impediments made it harder for women. Bathrooms are another example. Back then, Harvard had two classroom buildings, Austin and Langdell. Only Austin had a women’s bathroom. So if you were taking a class, or worse, an exam, in Langdell, you had to make a mad dash if you needed to use the bathroom. Yet, amazing from today’s perspective, we never complained about it. It was just the way things were.

An appendix to Judy Hope’s book, Pinstripes and Pearls, is revealing. The book is about her mid-60’s class at Harvard. The appendix reprints a report from Dean Griswold, about what it would cost to admit women—Harvard didn’t admit women until the 1950-1951 academic year. The largest cost was installing the women’s bathroom in the basement of Austin. That was the major expense the law school incurred to admit women.

One of the things Dean Griswold did—and I think it has been misunderstood—he had a dinner for the women in the first-year class. And he invited distinguished faculty members to be our companions. After dinner, we repaired to his living room, where chairs were set up in a semi-circle. The dean then asked each of us in turn to say what we were doing at the law school, occupying a seat that could be held by a man. Years later, Griswold told me he didn’t ask the question to be unkind. He said there were still doubting Thomases on the faculty who thought it was unwise to admit women. So the dean wanted to be armed with stories from the women themselves, about what use they would make of their legal education, so that he could satisfy his dubious colleagues.

Magill And what were the challenges when you graduated and looked for a job?

Ginsburg There was no Title VII, no national anti-discrimination laws, so law firms were up front about not wanting any women. Most federal judges were not interested in women, including some of the greatest judges of that era, prime among them, Judge Learned Hand. So, no matter how well you did in law school, it was hard to get that first job. Once you got the first job, the next would be easier, because you’d perform well and your boss could say, “She’s there whenever I need her, even on a Sunday.”

Justice O’Connor [LLB ’52 (BA ’50)] had such an experience. She couldn’t get a job even after graduating from law school at the top of her Stanford class. So she volunteered to work for a county attorney. She said, “I’ll work free for four months, then if you think I’m worth it, you can put me on the payroll.” That’s what it was like for the women of my generation. You can see why I am exhilarated about the changes we have witnessed over time.

Magill You’ve talked, Justice Ginsburg, about the various people who helped you. What do you think it was about those people who were willing to look beyond what was the common view at the time?

Ginsburg Gerry Gunther, who taught me at Columbia Law School after I transferred there for my third year, and was later on this faculty, was my biggest supporter. He was in charge of clerkships and I think he called every judge on the Second Circuit, every judge in the Eastern District, and every judge in the Southern District of New York trying to get me a clerkship. And then he came to Judge Palmieri, who regularly hired clerks from Columbia. Palmieri was a Columbia College graduate and a Columbia Law School graduate. But he expressed misgivings. He said, “Her record is fine, but she has a four-year-old daughter.” Legal employers were just beginning to entertain the idea of engaging a woman, but a mother was more than a bit much. Gerry wrote about this years later. I was unaware of it at the time. He wrote that he said to the judge, “Give her a chance and if she doesn’t turn out to be what you expect, there is a young man in her class going to a downtown firm who will come in and complete the clerkship.” That was the carrot. The stick, “If you don’t give her a chance, I will never recommend another Columbia clerk to you.” So with that aid, I got my district court clerkship.

At the time, I thought Judge Palmieri was willing to take a chance on me because he had two young daughters and was thinking about how he would want the world to treat them. That may have been in his mind when he hired me. One of his daughters is now a lawyer, the other is a doctor. I recall his annoyance when he thought his daughter was being treated unfairly during her medical training. As an advocate for equal citizenship stature for women, I tried to get judges to think about the opportunities they would like their daughters and granddaughters to have.

Magill So, you needed someone like Professor Gunther, a special and unusual person, to do what he did?

Ginsburg Yes. He was my teacher for Federal Courts. It was taught as a seminar at Columbia with an unusually excellent team of professors, Herbert Wechsler and Gerry Gunther. Gerry became a friend and sage advisor. He was the first person I called when President Clinton nominated me for the good job I now hold.

Magill Can you talk a little bit about your work in the 1970s for the ACLU? What prompted you to do that and what are your reflections on your experience?

Ginsburg When the revived women’s movement came alive in the late ’60s, early ’70s, I understood that it was the first time in history you could get courts to move on the disadvantageous treatment of women. Before that, even in the liberal Warren Court years, it was impossible. Recall a case decided by the Court in 1961, during Warren’s time, Hoyt v. Florida. The complainant was a woman who had killed her abusive, philandering husband by hitting his head with her young son’s baseball bat. Her thought was that if women served on her jury, they might better understand her state of mind—her feeling of rage, her inability to cope with the situation. They might not have acquitted her, but perhaps they would reject the murder charge and find her guilty of the lesser offense of manslaughter. But Hillsborough County, Florida, didn’t put women on the jury rolls. That was seen as a favor to women, because their place in society centered on home and family life. The Warren Court upheld Florida’s law. In fact, most of the justices didn’t understand what the complaint was about. Women could serve on a jury, but only if they went to the clerk’s office and volunteered. They didn’t have to serve if they didn’t volunteer, so they had the best of both worlds. Overlooked entirely was the point that if you are a citizen, you have obligations as well as rights and one obligation is to be part of the system of justice. That was the way things stood in ’61.

Magill In ’71, the turning point gender-discrimination case was decided by the then “conservative” Burger Court. Why? How do you explain the change?

Ginsburg Well, it had nothing to do with the Court being labeled liberal or conservative. The Court was catching up to the changes under way in society.

Magill This is Reed v. Reed, for which you wrote the petitioner’s brief?

Ginsburg Yes. It was the perfect case—perfect in the law, perfect in the facts. A mother whose son committed suicide wanted to be appointed administrator of his estate; some time later, the boy’s father, by then divorced from the mother, applied to be the administrator. The probate court judge told the bereaved mother, Sally Reed, “The law decides this controversy. It says, ‘As between persons equally entitled to administer a deceased person’s estate, males must be preferred to females.’ ”

Magill It’s almost like a law school hypothetical question on a test, isn’t it?

Ginsburg It was the perfect case, but it wasn’t a test case in the sense that we went out looking for a plaintiff. It seemed to me that many women, at that time, were awakening to the idea that they didn’t have to accept this sort of second-class treatment—this subordinate role. They hoped that the legal system might right what they experienced as a denial of the equal protection of the laws.

After the Reed case, I spent about 10 years of my life on women’s rights cases under the auspices of the ACLU Women’s Rights Project. The aim was to root out the gender-based classifications that riddled state and federal law books. So first you had to have a popular movement behind you. Public opinion was vitally important.

We tried to get legislative change and when that didn’t work, the Court was the next resort. In fact, in the ’70s, the legislature and the courts were involved in a kind of dialogue. The Court would say, “This gender line is unconstitutional,” and the legislature would then make amendments in that law and others like it. The Department of Justice and the U.S. Civil Rights Commission went through the entire U.S. Code to identify all of the gender-based differentials and Congress eliminated most of them. A few still remain, mainly in the immigration area.

Magill Is it correct that you worked on a case with Marty during that time?

Ginsburg Moritz v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. Yes. Marty said, “Here’s a case I think you should read.” Well, it was reported in a tax advance sheet and I responded, “Marty, you know I don’t read tax cases, that’s your domain.” “Read this one,” he said.

The complainant was a man in his sixties, who took great care of his mother, though she was 93. He wanted to take an income-tax deduction available for a child under the age of 12 or a disabled relative of any age that the taxpayer cared for in her home.

Moritz claimed this deduction and it was denied on the ground that the deduction was available only to a woman, not to a man. To Charles E. Moritz, this made no sense. He filed a brief pro se in the tax court. It was the soul of simplicity. He wrote, “Had I been a dutiful daughter, I could have taken this deduction. I’m a dutiful son. Why should that make any difference?”

The line the law drew rested on a stereotype: Women are caregivers, so a daughter would take care of her aging mother, but men are out in the world, earning a living, so they don’t take personal care of aging parents. That law was blind to the life Charles E. Moritz lived. We took his case from the tax court to the Tenth Circuit. Marty argued the tax part of it and I argued the equal protection part. A nephew of mine is a filmmaker. He has composed a script about the Moritz case. Perhaps someday he will find a producer.

Magill Do you know who would play you?

Ginsburg I know my nephew’s first choice, but I am not at liberty to say.

Magill What do you think are the barriers to women’s full citizenship today?

Ginsburg As I said before, almost all the explicit gender lines are gone, except in the immigration area. The Court, during my tenure, rendered two, in my judgment, very wrong decisions in that area—Miller v. Albright and Nguyen v. INS. But almost all the overt classifications are gone. There are virtually no closed doors anymore for women.

There remains this daunting problem: How can you live a good family life and a good work life? How do you combine those two? Women today, on the whole, take more responsibility for raising children than men do, though that’s changing. I see that in my children’s lives. My daughter’s husband is a loving, caring parent, as is my son. But we are still distant from the day when every worker thinks, “I have a home life and a work life and there must be a reasonable balance between those two.”

Magill And that’s a problem that’s difficult to get at through litigation?

Ginsburg Yes.

Magill It’s different from what you were attacking in the ’70s.

Ginsburg Legislation can help, for example, the Family and Medical Leave Act. That law sees the woman worker as central. What does she need to be able to do her job satisfactorily and still be able to attend to family needs? The Family and Medical Leave Act provides leave for care of a sick child, a sick spouse, a sick parent.

And day-care facilities—we’ve seen impressive progress in that area. When I was a law student at Columbia, there was one nursery school in the immediate vicinity. A child could attend from 9 to 12 or 2 to 5 and that was it.

A generation later, when Jane, my daughter, was appointed to the Columbia Law faculty, there were more than a dozen, full-day, day-care facilities in the area she and her husband could choose from.

Magill I’d like to ask you about your time on the Court now, if I may. Is there a certain kind of case that you find particularly difficult? Or do the difficult cases come in all different areas of law?

Ginsburg In the 13 years I was on the D.C. Circuit, one category of case was top of the difficult to fathom list. Marty called them “FERCy cases”—for Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. They didn’t necessarily come from that commission, but they were agency review cases involving many hours of work just to understand what was going on.

The Supreme Court has the luxury of selecting the cases it sets down for argument. Unlike courts of appeals, the Supreme Court’s docket includes very few must-decide cases. The Court grants review when it thinks the law of the United States needs straightening out. And that also means that in almost every case we take, there are two arguable sides to the story. The main reason for granting review is that other courts are divided on what the federal law is—on the meaning of a statute or the application of a constitutional provision. When good minds disagree on what the law is, the Supreme Court is obliged to step in so that there will be one law of the United States—not one law for the Ninth Circuit and another, say, for the Eighth Circuit.

Magill Having followed your jurisprudence, many of us know that you are passionate about procedure and federal courts issues. Why are you so passionate about procedure issues?

Ginsburg Why is easily answered: Civil Procedure was the first class I experienced in law school. From day one, I was totally engaged in that class. And I had one of the best teachers in the world, Ben Kaplan. Then as a law teacher, I taught procedure for 17 years. So that explains my affinity for the subject.

Now, I would love to write all of the Court’s procedure decisions, but the tradition is that no one can be a specialist, so I don’t get any more procedure cases than Justice Breyer [(BA ’59)], for example, who taught antitrust. In trade regulation cases, as in procedure cases, we are pooled as though we were generalists.

Magill And do you have a view about the relationship between procedure issues and rights issues?

Ginsburg Well, I am eternally hopeful, in both categories of cases, that the Court will get it right. Sometimes it does, sometimes it doesn’t.

Magill We have many students who are extremely passionate about rights issues but think of procedure as boring.

Ginsburg Procedure is tremendously important if you’re a lawyer. Sometimes, you may have a great civil rights case, but the choice is either to go down in defeat with a merits argument or win on a procedural ground. Knowing procedure stood me in good stead as a litigator and does even now, on the Court. Coming here in the car, I was reading a few law clerk pool memos on petitions for review. One captured my attention. I don’t know how the Court would come out on this if we reached the merits, I thought, but there’s a procedural impediment in this case. And the Court probably will agree on that.

Magill Do you think your experience as an advocate made you a different sort of justice than someone who didn’t have that experience?

Ginsburg Perhaps it made me a little more sensitive to being on the side of the bench, responding to questions rather than asking them. I will admit that sometimes when an argument isn’t going well, I wish I could change places with the advocate and present the argument I think the Court should hear.

Magill Some critique the Court for having too many justices who have very similar backgrounds. Do you think that’s a fair criticism?

Ginsburg One criticism is that too many of us were court of appeals judges and that Supreme Court justices don’t reflect the legal profession in the way it did, say, in the days of Earl Warren, the chief justice whose life was in politics—he was governor of this state, and he was a prosecutor, but never a judge. None of us has run for public office. Now retired Justice O’Connor was a member of her state senate. In fact, she was the speaker of the Arizona State Senate. She ran for a judgeship, too. But the rest of us lack that political experience.

Some of us were law teachers and there is a view that law teachers ask too many questions, too many long questions, harking back to their days in the classroom, where they could spin out hypothetical questions endlessly. The Court does benefit from a diversity of experience. For example, having three women on the Court makes a difference in that we have life experiences that our male colleagues don’t have.

Sometimes people ask me, “Well, how diverse is the Supreme Court?”

My stock reply, “Tremendously diverse—we represent every borough in the City of New York, except Staten Island. Justice Scalia is from Queens, Sotomayor grew up in the Bronx, Kagan is from Manhattan, and I’m from Brooklyn.”

Magill That’s very diverse.

Ginsburg There was a time when Arizona was disproportionately represented, when both the chief—Chief Justice Rehnquist [LLB ’52 (BA/MA ’48)]—and Justice O’Connor came to the Court from that sparsely populated state.

Magill If you could sit with any one of your predecessors on the Supreme Court, who would you choose?

Ginsburg John Marshall. My fondness for him came rather late. In college, I suffered through the multivolume Beveridge’s The Life of John Marshall. Then, while on the Court, I read Jean Edward Smith’s one-volume biography of Marshall [John Marshall: Defender of a Nation]. The man comes vibrantly to life in it and I was tremendously drawn to him from reading that book.

One quality of Marshall you can tell just from looking at the portraits of the chief justices in the conference room. We start with John Jay, the very first chief justice, who is wearing a robe with scarlet sleeves and gold trim. And then, two justices later, we see Marshall, who is very differently attired. Marshall’s idea was that we live in a democracy and there should be no royal symbols in our attire. We should all wear plain black. And so it has remained, except for the variety of collars Justice O’Connor and I wear.

Magill You have read some dissents from the bench, notably last spring. What do you think will happen to those dissents in the future? Are you hopeful that they will become majority opinions?

Ginsburg Yes. I think my dissent on the commerce clause part of the health care decision will. I anticipate it will become the accepted approach. It was the accepted approach, but the Court boldly changed it.

And I hope we will get a voting rights act that works. The decision striking the heart of the act, I hope, will not have staying power. The latest campaign finance decision, I also believe, will not endure. The Court will one day see that controlling the amount of money, whether it’s spending on or contributing to political campaigns, does not violate the First Amendment.

And then there’s an occasional case where the audience is Congress. The Lilly Ledbetter case is a classic example of that. The Court got it wrong, 5 to 4. I ended my dissenting opinion saying, “The ball is now in Congress’s ‘court’ to correct the error into which my colleagues have fallen.” And inside of two years, we had the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act.

Magill That’s quick work for Congress.

Ginsburg Yes. Wouldn’t happen today.

Magill Are you concerned about the direction of the Court, or is that too strong?

Ginsburg If you reflect on the history of the Court, there have been periods in which the Court is stemming the tide of progress in the nation at large. I think this may be one such time, but, eventually, this time will pass.

Think of the dissents over the history of our nation. Think of Justice Curtis, who was one of the two dissenters in the Dred Scott case. Or the first Justice Harlan, who dissented in the so-called Civil Rights Cases, in which the Court struck down a law passed by Congress, guaranteeing equal access to places of public accommodation. Think, too, of the dissenting opinions of Justice Holmes and Justice Brandeis around the time of World War I. Those dissents are, today, the law of the land. And I am hopeful that the dissents I have been part of in recent years will have a similar fate.

Magill The “Red scare” cases.

Ginsburg Yes. Today, those dissents are pillars of our First Amendment jurisprudence.

Magill Let me end on a light note. If you could be any opera diva, who would it be? What opera would you like to sing, and what part would you play?

Ginsburg I would be the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier. She is a woman who realizes she is no longer young. A transition is occurring in her life. I like the part of the Marschallin because she is a spirited woman, but at the same time she is a wise woman, understanding herself and the circumstances in which she lives.

Magill One more question. I assume you are aware that you have a following among young people, with a Tumblr dedicated to you and a rap song devoted to you.

Ginsburg “The Notorious RBG”!

Magill Yes!

Ginsburg By the time I tried to order one of those shirts, they had sold out completely. They had them in hoodies, sweatshirts, T-shirts.

Magill Well, I promise you—I will get you one.

Ginsburg I’m told a law student at NYU started this.

Magill Yes, that’s what I understand too. But the Tumblr page, which I’ve been on, has photographs of you with commentary and songs and poems. And it has lots of followers. I suspect that most people on Tumblr are 25 and under. I was wondering if your grandchildren know about your “rock-star” status among the 20-somethings and, if so, what they think of it.

Ginsburg I’d have to ask my 20-something granddaughter, now studying at Cambridge, England. I think she would like to have a “Notorious RBG” T-shirt.

Magill It’s wonderful to see you, Justice. Thank you.

Ginsburg Thank you. SL