LRAP: Stanford Celebrates 20 Years Of Public Service Innovation

Twenty years ago, Stanford Law School broke new ground by establishing the first student loan forgiveness program at a law school. Known today as the Miles and Nancy Rubin Loan Repayment Assistance Program (LRAP), it was unique in 1987— providing a vehicle for taking the often heavy burden of educational loans off the shoulders of graduates who pursue a career in public service.

But LRAP is much more than financial aid. Started with initial support from the Cummins Engine Foundation, Kenneth and Harle Montgomery, and Miles Rubin ’52 (BA ’50) and Nancy Rubin, LRAP is the backbone of Stanford Law School’s public service program. It not only helps attract students to the law school, it also enables those students to do public service, which might otherwise be impossible given high educational debt and low salaries.

“I believe that loan forgiveness in these circumstances is a moral obligation for Stanford,” says Larry Kramer, Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Dean. “The costs of legal education are such that the subsequent debt has made it impossible for some of our graduates to choose a career in one whole sector within the profession.”

Bridging the Salary Gap

The salary gap between the public and private sectors is telling—and that gap has grown over the last 20 years. Consider: In the late 1980s the average starting salary at top law firms was approximately $60,000, while in public service it was around $20,000—going up to $32,500 for the coveted Skadden fellowships. This was when tuition at Stanford Law School was just over $12,000 per year. Fast forward 20 years and starting salaries at top law firms now exceed $160,000 annually and tuition is projected to be almost $40,000 for the 2007/08 school year. Yet public service salaries have hardly budged, hovering around $40,000, perhaps going as high as $60,000 for a position in a major city.

As tuition has risen, so too has educational debt. Today, 80 percent of students at the law school receive some kind of financial aid. The average law school loan debt is approximately $100,000, with some students accumulating more than $150,000. For those joining a firm, paying this debt is feasible. For those interested in public service, this kind of debt can be prohibitive.

LRAP helps by first lending funds to graduates who choose a public service career to cover their monthly educational loan payments. Participants can stay in the program for up to ten years, and LRAP payments are calculated based on the assumption that alumni have placed their loans on a tenyear repayment plan. The funds loaned to program participants are forgiven at

WITNESSING THE DEVASTATION OF KATRINA: A ROAD TRIP WITH NANCY

Most Americans can’t forget the media images of the hurricane that roared across the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama in August 2005, taking with it thousands of lives—its force hurling casinos in the air, crumbling century-old buildings, and devastating entire communities with homes buried under a massive tidal surge.

The aftermath of the devastation revealed as much about American society as it did about the force of nature. We witnessed segregated poor and minority communities struggle to get assistance in the days following the storm and how they have been largely left out of the recovery and rebuilding effort. Six months after Katrina, thousands of families were still waiting for Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) trailers. Today, many are still waiting.

Helping the most vulnerable communities on the Gulf Coast quickly became a priority for the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law Community Development Initiative (CDI). We recruited hundreds of lawyers from across the country—including Stanford Law School’s clinic program—to assist people in their struggle to receive compensation for lost housing and lost employment. Today, the work continues.

I had the opportunity to travel back to the Gulf Coast with Nancy Rubin, one of the forces behind the Miles and Nancy Rubin Loan Repayment Assistance Program (LRAP). I met Nancy at an LRAP reception at Stanford shortly after Katrina. Not content to simply donate to the program, Miles and Nancy wanted to meet the participants and hear about their work. Nancy was familiar with my Skadden fellowship at CDI and my work in the Gulf Coast since the hurricane. She wanted to see the post-Katrina devastation firsthand, so we met in Mississippi in May 2006.

Our first visit was with Howard Page, a community advocate in Gulfport who had lost everything but the thin wooden frame of his family’s century-old home. We then walked along the shoreline, passing the foundation of a law office that had washed away. It was Reilly Morse’s practice, where I had worked as a Stanford Law student two years earlier.

Our next stop was a free legal clinic in East Biloxi, Mississippi, one of several clinics that we established after the storm to help isolated communities register for FEMA benefits. Nancy met a loan officer volunteering at the clinic. She broke down when he recounted his personal Katrina tragedy. Everyone in the room was bound together by a sense of loss.

Later that day, we met with Rose Johnson, founder of the North Gulfport Community Land Trust, a program that builds affordable housing in African-American neighborhoods. Paul Bogart, who came to Gulfport after the storm to design “green” modular homes, met us in Rose’s living room to draft a community partnership for building environmentally friendly, affordable homes for hurricane survivors.

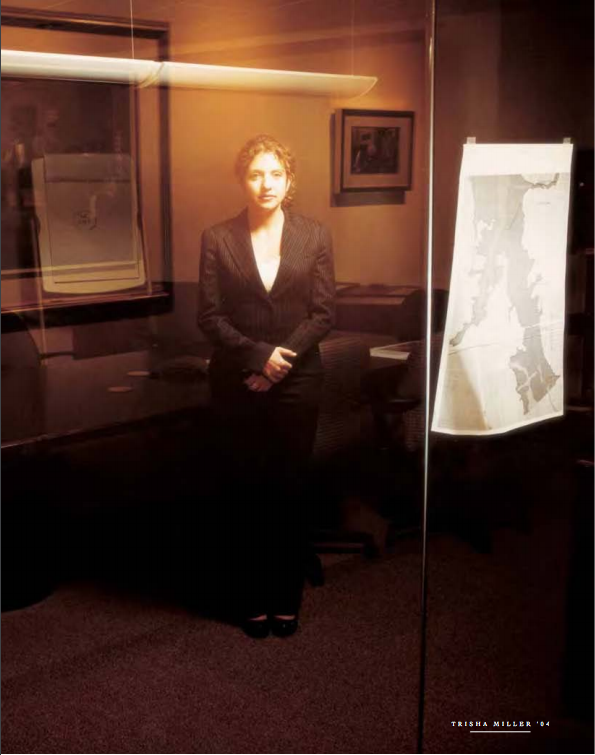

As this article goes to print, we are celebrating the ribbon-cutting ceremony for our first affordable green modular home erected on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in the center of the North Gulfport community. It is one house built by many hands. Unfortunately, only a few thousand homes in coastal Mississippi have been rebuilt, and more than 38,000 Mississippi families are still living in trailers. We need more hands.—TRISHA MILLER

TRISHA MILLER ‘04 is a staff attorney with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law where she directs CDI—a program that combines legal support, housing partnerships, and community planning. She launched this innovative legal assistance project as a Skadden fellow in 2004. The initiative continues to provide direct legal services—with the pro bono support of more than 100 national law firms, numerous law schools, and corporations—to nonprofit housing and economic development organizations across the South.

A LAST-MINUTE REPRIEVE: LRAP TAX EXEMPTION LEGISLATION

Ten years ago, law school loan forgiveness was a taxable benefit– which meant participants were liable for tens of thousands of dollars in tax on their forgiven loans by the time they left the program. It was the ultimate catch-22.

Frank Brucato, senior associate dean of administration and CFO at the law school, remembers that time well. An existing tax code, section 108f, allowed tax exemption for medical school loan repayment assistance programs. So Brucato enlisted the help of Stanford Law School’s Joseph Bankman, Ralph M. Parsons Professor of Law and Business, to draft legislation to extend tax exemption to law schools.

“I had LRAP participants calling me daily— asking what could be done to prevent the tax on their benefit,” says Brucato. “I felt a responsibility to our alumni to do something.”

The challenge for Bankman and Brucato was to get the proposed amendment into President Bill Clinton’s January 1997 budget. To accomplish this they needed, among other things, the support of the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee. The day before Thanksgiving in

AND JOSEPH BANKMAN

1996, Brucato called Bankman to ask a huge favor: Would Bankman give up his family vacation to join him in Washington for a special presentation to the assistant secretary of the treasury for tax policy? Yes, he would, was the answer back. The two flew to D.C. and spent the weekend making the case for tax exemption for law school loan forgiveness.

“When Joe spoke, the room just went quiet. The respect they had for his expertise was inspiring,” says Brucato.

The proposal made it into the January budget and was adopted that summer. Today, hundreds of LRAP participants at law schools across the country receive the benefit of loan forgiveness without taxation because of this effort.

set stages, with 25 percent forgiven after three years. Starting in the fifth year, 100 percent of funds already distributed are forgiven.

The Deciding Factor

Angela Schwartz ’04 readily praises the program. Though she worked throughout her undergraduate studies, she accumulated nearly $20,000 in educational loans. Knowing that her educational debt would approach $150,000 after law school, Schwartz took great care in assessing her law school options, comparing Stanford’s LRAP with the programs at other toptier schools to which she was admitted.

Schwartz met with Faye Deal, Stanford Law’s associate dean for admissions and financial aid, and, she says, “grilled her for a couple of hours until I was satisfied that I really could pursue a career in public interest law— and, with the help of LRAP, have a life.” Now a few years out of school—she knows that the program is everything Stanford says it is.

“LRAP was the deciding factor in my choice of Stanford Law School,” says Schwartz, who was a public interest fellow while at the law school, worked as a Skadden fellow with the National Center for Youth Law after graduation and is now a lawyer at the Public Interest Law Project in Oakland. She recently came back to Stanford to discuss LRAP with law school students, many of whom worry about the financial realities of pursuing a public service career. Schwartz fielded their questions, sharing with them the exciting news that she and her husband, also in public service, had just purchased a home in the Bay Area.

“You really can choose a public service career and, with the help of LRAP, have a fulfilling personal life,” Schwartz told them.

Those words are encouraging to Andrew Canter ’08, who came to Stanford for a joint degree program in public policy and law. Committed to public service, he was a Coro fellow before starting a master’s degree in public policy at the Kennedy School of Government, later combining it with a JD here. Canter did his homework before deciding on Stanford, and comparing LRAP programs was key. “Stanford Law School’s strong LRAP program was a significant factor in my choosing to come here,” says Canter. “It was also an indication of the school’s commitment to public service and its ability to attract the best in the field.”

A Growing Need

Canter’s statement is echoed by program participants, new and old. And here Stanford Law School has a breadth of experience to draw on. From five initial participants 20 years ago, LRAP has grown significantly and now

THE FIRST FIVE LRAP PARTICIPANTS

Lisa Millett Rau ’87 and Larry Krasner ’87 met in 1984 on their third day at Stanford Law School. They were both interested in public service: She had spent two years in the Peace Corps, and he was intent on defending the “little guy” as a trial lawyer. But as their student loan debt mounted, they wondered how they would be able to pursue their dreams after law school—get married, start a family, and live on public service salaries.

But help was on the way. In 1987, Stanford Law School announced the start of a new loan assistance program, LRAP, the first such program at any law school.

“Stanford was a dream school for me, but I didn’t think about how the cost would play into my career goals when I decided to attend,” says Rau, now a judge in the First Judicial District in Philadelphia. “Quite literally, I could not have taken a career in public service if it had not been for this program.”

Krasner landed a position with the public defender’s office in Philadelphia after graduation. Meanwhile, Rau turned down a lucrative firm position to work with Philadelphia’s Public Interest Law Center. Occasionally they would look at each other and say, “Want to try life at a big firm?” But they never did.

“I’ve been able to do what I wanted to do because of LRAP,” says Krasner, now a partner in his own practice.

This is an oft-heard theme among LRAP participants, who describe the program as an enabler—the thing that made it financially feasible to follow the career path of their choice.

Tom Waldo ’87 and his wife, Anitra ’87, had a child right after they graduated from Stanford Law. Anitra put off starting a career to raise the children, and living on one public service salary was a challenge.

“I don’t think I could have done this job without LRAP,” says Waldo, an environmentalist who took a position with Earthjustice in Alaska just after the Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989 and who works there still. “My salary was so low that when we moved to Juneau we qualified for public housing.”

C.J. Callen ’87 came to Stanford Law School intent on pursuing a legal career in public service. While most of her colleagues were focused on big firm careers, she was inspired by faculty such as Jerry López and by her externship with the Public Defender Service in Washington, D.C. Today, she is a director at Northern California Grantmakers—an organization that works to increase the effectiveness of foundations and other philanthropic entities.

“Being at Stanford and getting the skills that I did allowed me to be creative in developing a career path,” she says. “LRAP made it possible.”

Christopher Ho ’87 had one goal when he began his legal studies: to qualify for legislative work on Capitol Hill so he could craft legislation. When he arrived on campus, he discovered the East Palo Alto Community Law Project, which allowed students to gain legal experience while helping low-income members of the community. The experience changed his thinking, and he decided to pursue a public service legal career instead.

“What was critical to my career choice was getting exposure to public interest law through the law project,” says Ho, now a senior staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society—Employment Law Center in San Francisco. “But LRAP was critical to my deciding that I could actually make a go of it.”

MILES AND NANCY RUBIN: A LIFE IN PUBLIC SERVICE

It’s difficult to discuss Stanford Law School’s commitment to public service without also talking about Miles Rubin ’52 (BA ’50) and Nancy Rubin and the loan assistance program that bears their name. The program has made it possible for more than 350 graduates to pursue their dreams of a public service career without carrying the burden of law school debt on their own. The first program of its kind, the Miles and Nancy Rubin Loan Repayment Assistance Program (LRAP) provides loan repayment assistance and eventually loan forgiveness to graduates pursuing careers in public service and nonprofit fields of law.

“The law school must encourage the best and brightest graduates to pursue a career in public service,” says Miles. “These individuals will change the tides for others and deliver on the most fundamental dreams of our society. Nancy and I are proud of what Stanford Law School students and graduates are contributing.”

Involved in public service and social action since the early days of his legal and business career, Miles makes time for public service issues that he considers important to cultural change. He believes that all attorneys can and should do the same.

“Whether directing political campaigns, public service programs, or starting up new businesses, I’ve found the training and the problem-solving approach of law school graduates make them ideal for executive staffing,” says Miles.

During his time at Stanford in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Miles was troubled by the lack of diversity in the school’s student population. This concern led him, together with Victor Palmieri ’54 (BA ’51), to establish the Carl B. Spaeth Minority Scholarship Fund. In the 1950s, as general counsel of Reliance Manufacturing, he led the effort to fully integrate the company’s large plants located in the Deep South, reversing a decades-old policy of racial discrimination. In the 1970s he co-founded Energy Action, a nonprofit dedicated to American energy independence and conservation, and in the 1980s he was active in addressing apartheid and founded the Woza Africa Foundation. His activities today are focused on limiting global warming with the development of zero-emission all-electric vehicles.

The spark for Nancy’s initiatives in public service came early in her career as an elementary school teacher, when she became frustrated by the lack of equal access to quality education for all children. Nancy’s 30-plus years in public service include extensive work in human rights and humanitarian issues in addition to helping to build a “culture of service” in the country through her efforts with the Corporation for National Service and AmeriCorps. She has worked with the women’s rights movement and the international development community and chaired the Committee on Women, Law & Development, which brought legal literacy clinics to Asia, Africa, and Latin America. She served in both the Carter and Clinton administrations and was appointed U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in 1996. She has worked in more than 20 countries in efforts to advance social, economic, and political rights.

But what motivates Nancy and Miles to so strongly support lawyers in their pursuit of a public service career?

“Few have more tools to make significant progress throughout society than those entering LRAP,” they say. “Stanford Law School graduates have legal training, passion, and imagination. For those who turn down lucrative firm offers to make justice and opportunity real for those in need, we feel privileged to help to soften the sacrifice.”

supports approximately 100 alumni each year. Since 1987, it has benefited more than 350 alumni, some having joined the program temporarily before moving on to other fields of law and others having stayed the full ten years. According to Frank Brucato, senior associate dean of administration and CFO at the law school, participation in the program is now outpacing its endowment—a challenge the law school hopes to address as part of its ongoing campaign.

“We’re a victim of our own success,” says Brucato, who estimates that the program will require an additional $7 million to endow. “Thanks to Miles and Nancy Rubin and their matching challenge gifts to LRAP, we’re well on our way. But there is still a lot that needs to be done to secure the program’s future.”

The sheer variety of work done by LRAP participants and the work they continue to do after leaving the program is impressive. Some are with the Department of Justice; others are public defenders. Some have begun nonprofit agencies or public interest law firms of their own; others have been elected to public office or appointed to government agencies or the bench. With the benefit of a Stanford Law School education, many have risen to positions of leadership. But it is the benefit of LRAP that helped to make their career choices possible and ties these alumni stories together.

For more information about Stanford Law School’s LRAP, visit www.law.stanford.edu/program/tuition/assistance/