Guarding Democracy

In early spring, with the novel corona-virus shutting down many aspects of American life and buffeting the primary election season in states across the country, widespread concern arose that the November presidential election might become the pandemic’s next victim. Nate Persily, James B. McClatchy Professor of Law, formulated a plan to keep the most basic of democratic institutions functioning.

His prescription includes emergency federal funding to help states expand voting by mail so citizens would not have to choose between protecting their health and exercising the franchise. It also calls for enlisting the National Guard to keep polls open for those millions of citizens who still want to vote in person. And it includes launching a clearinghouse for state election officials to share tips for keeping voters safe. (Think painter’s tape to mark off six-foot increments to help keep voters from getting too close to each other, for example.)

“The nation must act now to ensure that there will be no doubt … that the elections will be conducted on schedule and that they will be free and fair,” Persily wrote in a March 2020 article with MIT professor Charles Stewart on the Lawfare blog titled “Ten Recommendations to Ensure a Healthy and Trustworthy 2020 Election.” “Doing so requires an effort in election resilience that is unprecedented in American history.”

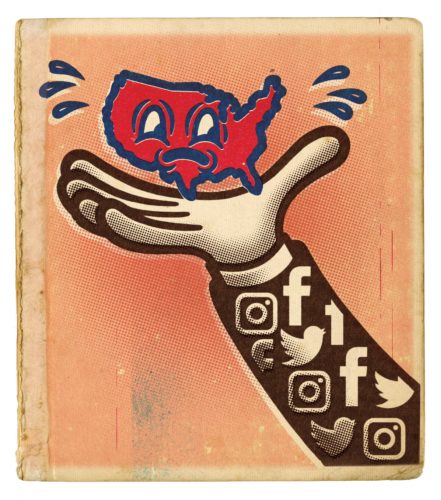

Even before COVID-19, the health of democracy in the U.S. and around the world has been challenged — by political polarization and digital disinformation. And Persily, JD ’98, has been at the leading edge of the “law of democracy,” which addresses such issues as voting rights, political parties, campaign finance, redistricting, and election administration.

He has served as a court-appointed expert to help craft congressional and legislative districting plans for Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, New York, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania. He has also served as senior research director for the Presidential Commission on Election Administration, which identified ways to improve the country’s voting infrastructure, including contingency planning for natural disasters and emergencies.

His current work examines the impact of changing technology on political communication, campaigns, and election administration. At Stanford, he helped launch the Cyber Policy Center (CPC), a cross-disciplinary research center at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI), which examines issues affecting technology, governance, and public policy.

In partisan times, Persily stands out, self-consciously independent and driven by empirical evidence and history, reflecting a PhD from Berkeley to go along with his Stanford Law degree.

“Nate is an energetic, renaissance guy whose impact is felt well-beyond the law school,” says Rob Reich, professor of political science, who, with Persily and Frank Fukuyama, a senior FSI fellow, leads the university’s multi-disciplinary Program on Democracy and the Internet, one of four programs housed at CPC.

Persily was one of the first academics to foresee the transformative impact of the internet and of social media on democracy as well as the need for new rules for politicking in the digital future.

More than a year before the 2016 presidential election and its aftermath, Persily wrote about social media platforms suddenly setting the terms of the national political debate as the internet eclipsed television advertising as the country’s dominant form of political communication.

In an article in The American Interest, a bimonthly magazine focusing on foreign policy, international affairs, global economics, and military matters, he warned of a new, largely unregulated era of “anarchic electoral politics, with ideological echo chambers, massive anonymous spending, and microtargeting of unprecedented precision,” as propagandists and fake-news purveyors fill a void created by the declining influence of political parties and the mainstream media.

He led a study of the global challenges to electoral integrity of digital technologies and social media platforms for the Kofi Annan Foundation. He helped launch an innovative partnership in which Facebook is making a trove of information available to social science researchers to address basic questions about social media and politics that previously had been left to armchair speculation.

“Democracy needs to adapt,” Persily says. “We need to develop institutions that are global in their perspective, which can rein in the corporations that are now becoming the de facto regulators of the political process. This is easier said than done, but I think it has to be done.”

“Nate believes this is a moment in history that is going to have a tremendous impact on our democratic futures,” says Kelly Born, the CPC’s executive director, who helped found and lead the Madison Project at the Hewlett Foundation before coming to Stanford. Last year, the cyber center issued what remains the only bipartisan, independent analysis of Russia’s attack on the 2016 election, including detailed policy recommendations for heading off future interference.

Now, in 2020, a pandemic has been added to the daunting mix of issues the U.S. will face as it prepares to go to the polls in the fall.

Watch video of Stanford researchers team with MIT for the Healthy Elections Project

The CPC has been tracking steps social media platforms are taking to facilitate connections between the public and health care providers. It has investigated misinformation about sources and cures, as the virus has been fertile ground for speculation and conspiracy theories.

The pandemic has also made manifest how ill-prepared states are to hold elections in a time of illness and social distancing, with Ohio canceling its presidential primary at the last minute and Wisconsin holding its despite a shortage of workers and polling places. In more than a dozen articles, Persily has been making the case for greatly expanded voting by mail, but he also acknowledges that it’s a heavy lift, financially, operationally, and politically. Only a handful of states currently have all-mail voting, but extending the practice nationally could cost $2 billion or more and pose new administrative challenges for handling mountains of paper ballots.

Because millions of Americans will continue voting in person, Persily says that election officials also need to be focusing on re-engineering the polling place experience to protect people’s health. Finding reliable qualified temporary workers to monitor the polls, he notes, is difficult even in normal times. A U.S. Election Assistance Commission survey found that two-thirds of America’s local jurisdictions couldn’t recruit enough poll workers on Election Day 2016.

Persily sees the National Guard as a ready and reliable option. By mid-April this year, guard members around the country were already responding to the COVID-19 crisis by disinfecting first-responder vehicles, transporting medical supplies, and making protective facemasks. Helping with the election is a natural extension of the guard’s public service work.

Besides backfilling poll workers, Persily says, guard members could help sanitize polling sites and supply logistical capacity to transport election materials. Guard units also have systems in place to track soldiers who speak multiple languages, a potential critical capability at some precincts. The key, he says, is early planning.

“American democracy has endured a civil war, two world wars and the flu pandemic of 1918. The U.S. held elections during all of those life-changing and democracy-endangering events,” Persily and Stewart wrote in the Lawfare article. “The COVID-19 pandemic represents a unique challenge. It requires an extraordinary commitment at all levels of government — and from the media, political parties, campaigns, and voters. The country can meet this challenge if Americans begin to prepare immediately.” SL