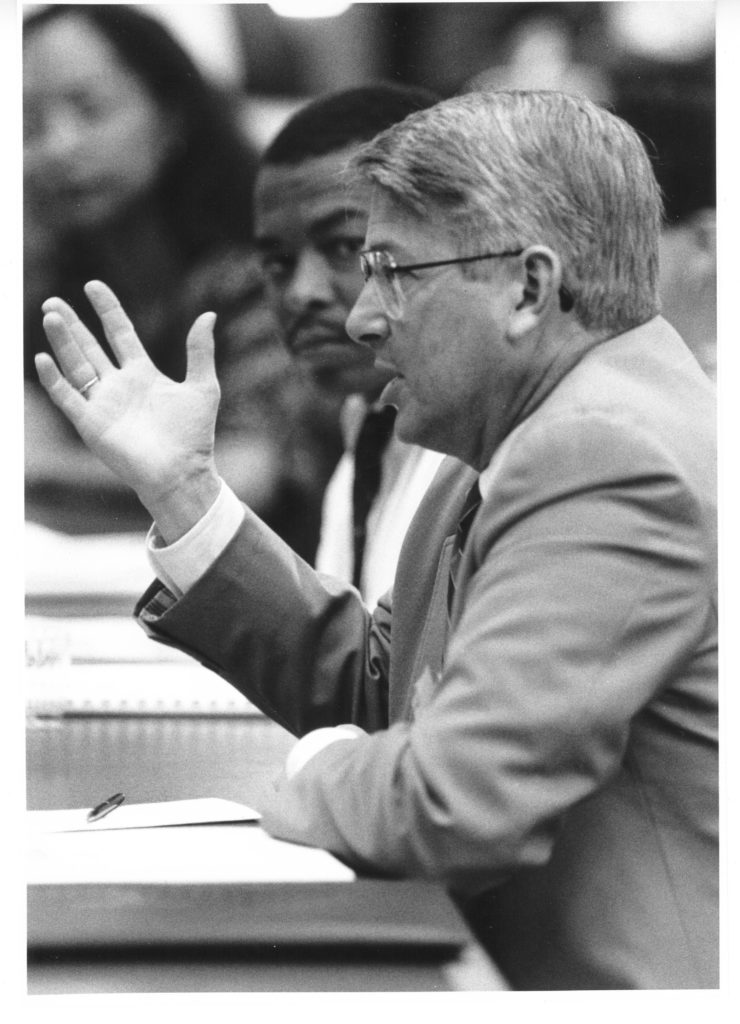

On Government Service, Silicon Valley and the Law: James C. Gaither, legendary Silicon Valley lawyer and VC, in conversation with Professor Robert Daines

James C. Gaither, JD ’64 Partner, Sutter Hill Ventures

Jim Gaither graduated from law school in 1964 right as the world was exploding. President Johnson delivered his Great Society speech, volunteers working in Mississippi for the Freedom Summer were murdered, the Vietnam War escalated with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and the Civil Rights Act was passed. Gaither was among the many called into public service by President Kennedy, who had been assassinated the autumn before. JD in hand, he headed to the nation’s capital—first clerking for Chief Justice Earl Warren, where he spent part of his time helping Warren finalize the report on the assassination of President Kennedy. The next year, he joined the Department of Justice, spending a year as special assistant in the Civil Division before being recruited to the White House as a staff assistant to President Johnson.

And so, just two years out of law school, Gaither held a key position in government. He was asked to pull together ideas for Johnson’s legislative program—running task forces on everything from foreign aid to trade to health to education—and helping to craft some of the most important legislation that the country has known.

Gaither recalls it as a time when country came first saying, “I don’t remember any mention of party or politics.” But he does remember one initiative that he had pushed hard for that was not taken up by Johnson—a ban on smoking. This was, perhaps, personal for Gaither, who had watched his father, H. Rowan Gaither, die of lung cancer in 1961.

“He meant everything to me. We were extremely close. He was given two weeks to live when he was 48 and fortunately he lived for three years with treatment. And I was with him most of that time,” said Gaither before sitting down for the interview that follows. “So, we spent as much time together during that three-year period as we probably would’ve had he lived a full life.”

The elder Gaither was a towering figure, who started off teaching at the University of California, Berkeley, with Roger Traynor and working with physicists, many of whom became Nobel Prize winners. “That had quite a dramatic impact on his life. He then went to the Roosevelt administration’s Farm Credit System—said it was the best ‘law firm’ that anyone could possibly work with. George Ball, Adlai Stevenson, Carl Spaeth, later dean of Stanford Law School, and my dad were the four lawyers in the office.” His father went on to help found the RAND Corporation and was one of the early people at MITRE Corp. He also headed the Ford Foundation. “Interestingly, his executive assistant working on the study for the Ford Foundation was Betty Moore, Gordon Moore’s wife, which is a long chain that gets back to me now, working with Gordon and Betty.”

Rowan Gaither was also an early venture capital investor, co-founding and becoming general partner of Draper, Gaither & Anderson (DG&A). “I don’t know how he first got involved in the investment business, but he was close to the original investors in DG&A: Lazard Frères and Rockefeller, but particularly Lazard, who had done the initial public offering for the Ford Motor Company and the selling of the Ford Foundation stock.” So, his father managed the offering and was the tie to investors in the first venture capital partnership on the West Coast.

“He had a pretty big influence on me in a bunch of ways. It was certainly important when I went to law school. I was hell bent to do well because he had done well. It really was a motivational force in my life,” Gaither recalls.

After Nixon was elected, Gaither left D.C. and headed back to the Bay Area, settling in at Cooley law firm in 1969, where he thrived in the venture capital formation business. He became managing partner in 1984—putting his imprint on the firm by opening an office in Palo Alto, bringing it to the center of the tech economy and focusing on emerging companies. He also hired Steve Neal, JD ’73, to build the litigation practice.

Gaither was an influential attorney in Silicon Valley right as it was becoming the center for startup businesses and he helped lay the legal foundation for the unique place for emerging technology companies that it is today.

In 2000, Gaither launched a third career, this time in VC as a partner in Sutter Hill Ventures, a position he still holds. Working with Sutter Hill (and the Cooley firm), he helped companies including NVIDIA Corp., Makena Capital, Amylin, and Dionex get their start. He has been recognized as a top tech VC by Forbes magazine’s “Midas List,” but deflects any notion of a secret sauce.

“You know, if you want to succeed in the venture capital business, just find great leaders. If you take any VC firm going back 50 years, that’s the one criterion that is almost certain to have made a difference. It’s leadership, it isn’t technology alone,” he says.

Alongside an extraordinary career, Gaither has served on several corporate boards (Amylin, Levi Strauss, NVIDIA, Siebel Systems, and Varian Associates) and as chairman of the boards of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the James Irvine Foundation. He also served as trustee of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the RAND Corporation. In the education sphere, after serving as chair of the boards of Marin Country Day School and the Branson School in Marin County, he has spent countless hours giving back to Stanford, grateful to the university for the education that he credits with much of his career success—raising money, helping create the Stanford Management Company to oversee the university’s endowment and ensure its future, serving as chairman of the Stanford Board, and advising university presidents Donald Kennedy, Gerhard Casper, and John Hennessy.

In 2006, Gaither received Stanford Associates’ highest volunteer service award, the Degree of Uncommon Man, which takes its name from Herbert Hoover’s description of the importance of leadership: “in other words, to be uncommon.” Gaither is certainly that—and more.

Robert Daines, Pritzker Professor of Law and Business and Associate Dean of Global Programs and Graduate Study

Speaking at the 2012 Stanford Law Graduation ceremony, Robert Daines recalled a time, just after he began teaching, when he was focused on securing tenure and working very hard. His wife, because he always seemed to be working, locked him in his office “so he could really focus.” He got the message.

“Being true to the relationships and people in your life will not be easy, in part because you are all so driven to succeed, to do something important, and to avoid seeming, if only to yourself, inconsequential,” Daines, the Pritzker Professor of Law and Business, told the Class of 2012, who had honored him with the John Bingham Hurlbut Award for Excellence in Teaching. He urged the new lawyers to find the time and energy for what matters to them—without neglecting the people in their lives. “I leave it to you to decide whether people can be truly happy if they reform prisons and right a string of wrong precedents, but make a mess of their relationships with friends and family; if they argue brilliantly in court, but too often with their loved ones; if politicians and reporters return their calls, but their children won’t talk to them.”

It is this balanced sensibility that Daines brings to his teaching and his scholarship.

Recently appointed associate dean of global programs and graduate study, he highlights the broad focus and the need to see issues from all sides, not just from the American vantage point, as an imperative in today’s legal practice. What does the limitation on free speech in Turkey mean to a company, such as Twitter? How will a fire in a factory in Bangladesh affect American apparel companies? What happens when governments threaten to expropriate intellectual and real property or when U.S. litigators face court rulings abroad that may conflict with the orders of U.S. courts? What legal problems arise when firms go global? Along with teaching International Business Transactions and Litigation, Daines also teaches Corporations, Introduction to Corporate Finance, Mergers and Acquisitions, among others.

As senior faculty of the Rock Center for Corporate Governance and professor of finance (by courtesy) at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, Daines focuses on law and finance—exploring CEO pay, corporate governance, mergers and acquisitions, mandatory disclosure regulations, shareholder voting, and takeover defenses. And he brings practical experience to both the classroom and his research. Before entering academia, he was an investment banker at Goldman Sachs, advising firms on bank and bond financings. Earlier, he clerked for Judge Ralph K. Winter of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

- By Sharon Driscoll

DAINES Let’s start with law school. You said you were motivated to work hard, and you obviously did, since you graduated and got a clerkship with Chief Justice Earl Warren.

GAITHER Stanford Law School was really the defining moment of my education, where extraordinary faculty members really taught me how to think: Byron Sher, Bill Baxter, JD ’56 (BA ’51), Keith Mann, Charlie Meyers, John Hurlbut, Herb Packer, and many others but probably most significantly Byron Sher and Bill Baxter. It was an incredible educational experience for me.

“… THE TIMES WERE AFFECTED PRETTY DRAMATICALLY BY PRESIDENT KENNEDY AND WITH HIM CAME AN INFLUX OF YOUNG PEOPLE INTO THE GOVERNMENT… IT MADE FOR A VERY INTERESTING TIME TO BE THERE—A BUNCH OF WONDERFUL PEOPLE WHO REALLY CARED. ”

– JAMES C. GAITHER, JD ’64

DAINES And what was it like to clerk for Chief Justice Earl Warren?

GAITHER It was a wonderful experience. Chief Warren’s clerks reviewed about fifteen hundred petitions from prisoners all over the country in addition to the fifteen hundred to two thousand cases coming to the Court each year, which all the other clerks worked on. The Chief was great to work with. We would prepare memoranda on each case coming before the Court, summarizing the arguments and making our recommendations. On occasion, he would call us in to discuss a case before argument but most of our interaction was drafting opinions for him when he took the lead role. He assigned most cases to other justices but occasionally, when he felt strongly, he’d take responsibility for drafting the opinion and circulating it to the justices who had agreed with his position. Two of the cases assigned to me were the first poll tax case, which held the tax to be unconstitutional, basically because it was designed to prevent black people who held no property from voting, and the first conglomerate merger case, which the Court blocked. The latter opinion was very tough for me, because I had written a law review note at law school arguing that there was little evidence of anti-competitive power or behavior. In reviewing my draft with me, he smiled and said, “Remember, Jim, this is an incipiency statute; the law requires us to stop these things early.”

But working for him was quite an experience. He cared very deeply about the outcome and could not believe that bad outcomes were intended by the Congress. Now that’s a wonderful view for one member of the Court; I’m not sure nine would work. But he was a terrific justice, who cared deeply about civil rights and the voting rights of all people.

DAINES You then went to the Civil Division of DOJ in 1965 and 1966. What was it like to be a young lawyer in government service at such a historic time?

GAITHER You know, the times were affected pretty dramatically by President Kennedy and with him came an influx of young people into the government that I’m sure we haven’t seen since. But it made for a very interesting time to be there—a bunch of wonderful people who really cared. And that was true during my time in the Justice Department. And then Nick Katzenbach [attorney general in the Johnson administration] recommended that I go over to the White House to replace Bill Moyers in developing the legislative program.

DAINES That was what, 1966?

GAITHER Yeah, but I turned it down at first because I think all of the Kennedys were suspicious of Johnson, as I was before I went. But Katzenbach came to me a second time and said, “Jim, you’re crazy not to take this opportunity. Just put the legislative program together. You’ll never have an experience like this.”

DAINES What was it like working on President Johnson’s legislative program—which was one of the most productive in our country’s history?

GAITHER I went, knowing nothing. I had the responsibility for putting ideas together for the legislative program for everything from foreign aid and trade through health and education. I ran probably 30 task forces a year and, with Joe Califano [President Johnson’s top domestic aide], presented the legislative program to Johnson each year. And, as you know, almost every major social program that the country has today had its origins during that period. Johnson worked unbelievably hard to drive that process. We would start at the end of March, travel around the country talking to experts everywhere, saying that “President Johnson doesn’t have any directions for you. He wants to know what you think would be best for the country.” So we’d go to Yale and its president Kingman Brewster would organize ten people to come in and they’d give us their advice; then we’d go down to Atlanta and we’d come out here. And so on. After about 10 of those visits, we’d organize a list of ideas, then meet internally, to decide which ones seemed to be worth pursuing, and then lastly, put task forces together. For those that were most important, we’d organize outside task forces. For example, we recruited George Shultz to head the task force on man-power, which later led to Shultz becoming secretary of labor under a Republican president. He’s embarrassed to hear that story, but it’s true—Johnson gave him his start in politics.

Anyway, each task force would have 10 to 15 people from the outside, and our advice to them was “please just be very candid about what you think the country ought to do. We’re going to present to the president, it’s completely off the record, we will never quote you.” And as far as I know, none of those task force reports have ever been released. But they formed the basis for the legislative program. Then, we’d take a second tier of ideas and organize another 15 task forces of people within the government to look at. We’d bring it all together in the early fall and then Califano and I would present it to the Cabinet. By early December, we pretty much had the program for the next year ready.

DAINES Did you present the proposed legislative program to Johnson?

GAITHER Yes. We’d fly down to President Johnson’s ranch in December and present it to him. The only thing we had to be careful of was that he loved new ideas, and he’d pick an idea and the next morning you would read about it in the paper. But other than that, we’d go through everything. I only remember a couple of things he said no to—a ban on smoking was one. He said, “You go get me one senator from the South who’ll support this and I’ll back you. If you can’t get one, don’t let me burn up in flames over that one.” But that was about the only thing he ever turned down that we recommended.

We would then prepare the State of the Union and messages to the Congress on each major subject. So there would be one on health, one on education, one on foreign aid and trade, and the departments would put the legislation together before that message was delivered. The day after the State of the Union, the first message would be delivered to Congress, and we would include in it all of the legislation that was described in the president’s message. And we did that every year. I think Bill Moyers was probably the designer of that process, along with Califano and his staff. There were three of us who basically ran that process after Moyers moved up in the White House. Contrast that with the amount of thought that goes into anything presented to the Congress today.

“WE REALLY WORKED VERY HARD. AND I DON’T REMEMBER ANY MENTION OF PARTY OR POLITICS. WE WERE TRYING TO DO WHAT WE THOUGHT WAS RIGHT FOR THE COUNTRY.”

– JAMES C. GAITHER, JD ’ 6 4

DAINES Is there anything from that time that you’re especially proud of?

GAITHER Almost all of it. We really worked very hard. And I don’t remember any mention of party or politics. We were trying to do what we thought was right for the country. And if you look at everything done in the manpower area, everything done in education, most everything in health—Peter Bing [executive director of the National Advisory Commission on Health Manpower during the Johnson administration] was one of the chief architects in those days of that—and the protections for Native American and other minorities, all of the work on the environment—almost all of the clean air, clean water legislation—it all started during that period. And we worked on all of those bills. I was more of an observer on the civil rights stuff. Larry O’Brien was the congressional liaison and we met every couple of weeks, a small group of us. The whole White House staff was about 15 people, so it was a very different era. Larry would have a list of about 70 bills that we had up in the Congress and the first four, in terms of priorities, were the civil rights bills. And Larry kept reporting that he couldn’t get them out of committee, and after 9 to 12 months, Johnson walked in one day and said, “Larry, you’re wrong. We’re going to get those bills out of committee this week, and don’t ever ask me what I had to give [Senate Minority Leader] Everett Dirksen to get those bills out of committee.” That week, those bills finally got out of committee and passed the Senate and the House. Johnson had convinced Dirksen that he would go down in history as having done the right thing for the country. And Dirksen didn’t get anything for himself, but part of the bargain was that he got a lot of stuff for Illinois. He got post office trucks, research centers, and every damn thing he wanted for Illinois.

DAINES Interesting. Did you work on anything else in the Johnson administration?

GAITHER Yeah. Joe and I negotiated with Marian Wright Edelman [founder of the Children’s Defense Fund] at the end of the Poor People’s March on Washington. She is a wonderful woman. And she was right about everything she asked for. Joe and I agreed to almost all of it. She had done so much homework. I remember she started out with the Agriculture Department and she said, “Look, let’s just go through all of the advisory committees in Agriculture.” She basically showed us that there were only white males on the committees. And she went through the whole government that way—the discrimination against women, against minorities—and asked for our commitment that we would go to work on it. We did the same thing with the employment service, which was basically devoted to the children of white union members. No blacks.

So, anyway, working on things like that, trying to deal with the disorders in the country after the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and of Bobby Kennedy were really something. And most all of that was managed out of Califano’s office, where I was. So we were managing the federal troops, calling out the National Guard, and all of that stuff. And trying to bring King’s family to the White House and asking the country to please stop all of the rioting. Anyway, it was an interesting period for a younger guy.

DAINES What an impact! Why did you leave the government?

GAITHER Well, John Robson [Johnson’s under secretary of transportation] and I were working on the materials for the Johnson campaign—basically little pamphlets that people could stick in their pockets, talking about the accomplishments. Then, I believe on March 31st, when Johnson decided not to run, the notion of sticking around for the Nixon administration was never an option. They didn’t trust any of us at all. Even on the day before the inauguration, Pat Moynihan [an adviser to President Nixon early in his career] finally called and said, “Hey, can you guys tell us what we should do if a riot breaks out tomorrow?” That was the first time they talked seriously to us. It was a very strange transition, driven by Nixon, who trusted no one. The outgoing administration packs everything and picks up all the boxes and leaves, so if you don’t pay attention during the transition, it’s pretty hard.

DAINES Did you join Cooley right away?

GAITHER I think that’s right. I had gone into the service after college [serving as a captain in the U.S. Marine Corps.] before law school. I decided, ultimately, that I wanted to come back to Northern California and, while I would never have gone directly from law school to a firm that my father had been with, I figured at that point that I’d done enough that I could probably claim that I would be admitted without the family tie. So I joined the Cooley firm. We were 25 at that time and I guess they’re now almost 1,000.

DAINES How was the transition from government? Did you jump right into transactional practice?

GAITHER The early years at Cooley were very difficult because I knew nothing, and all the experience on the Supreme Court, trying to figure out what the law ought to be rather than what it was, was not very helpful. But I had a lot of business coming to me—in part from people like Ed Huddleson, who was the senior guy in the firm, and from the outside. So the only way I could survive was to get world-class help, and my partner Tony Gilbert and a few others really made me look good for years.

I then got into the venture capital fund formation side, starting out forming Sutter Hill Ventures as a partnership. It was the first one I did. And you’ll be pleased to know that the partnership agreement that I put together in 1969 is still the Sutter Hill partners’ agreement. And the limited partners are constantly saying, “It’s time we update that,” and our response is look, it’s worked for this long. It’s worked well for you and it’s worked well for the firm and we’re not changing anything.

So we were doing a lot of the early work in the VC world. Almost all of the VCs came to Cooley for help with forming new venture capital funds and that’s where we had quite a presence—probably an 80 percent market share. It’s still very, very high. Those firms gave us lots of business.

DAINES What about tech business?

GAITHER Sonsini really took the computer and peripheral side of the business, and we were hurt pretty badly by not being down here. I tried with the then-senior management to open an office in Palo Alto and they were afraid that if we did it, people would split off. The next year, they asked me to become managing partner and we opened in Palo Alto. And then we became quite dominant in life sciences and software—and that’s what changed the world for the firm. With AMGEN, Genentech, Gilead—you name it. They all came to Cooley. And the same thing was happening on the software side. So all of a sudden, we were competitive with the Wilson Sonsini crowd and I think we’ve won that war now. And we became the two dominant firms in the technology field.

DAINES Did you make a strategic choice to go after life sciences business?

GAITHER Strategically, that’s what we were trying to do, but did we focus on those sectors? No. We were focused on emerging companies and how to build that practice, but not that we would develop skills in life sciences, then go and try to get it. That wasn’t the way we did it. So most of it was coming through venture capital firms that we were working with. That we became dominant in those two areas was more about who brought us the business, and the fact that we got the leading companies. Jensen Huang from NVIDIA came to me; Tom Siebel came to me for help in forming Siebel Systems. Bill Bowes brought us AMGEN and Applied Biosystems. Bob Swanson brought us Genentech.

DAINES As managing partner at Cooley, what kind of firm were you trying to build? Did you have a particular culture or kind of lawyer in mind?

GAITHER We really had what we thought was a very different culture. We prided ourselves on the quality of the work and our unwillingness to take on conflicts, which a lot of people were willing to do. They would take on both sides of a transaction. We wouldn’t do that. And we wanted to see if we could keep it as one firm. While we looked at a couple of big mergers, sitting in the middle of the legal market with fewer than 50 lawyers is a really hard space to be in, we worked our way through that and as we expanded—particularly to Palo Alto initially and then to San Diego—we worked very hard to see that the leadership was from the original core group. And that’s been true ever since: integrity, quality, and one firm. And the focus for as long as I was there was to build leadership position in the emerging technology company arena. And we had a terrific business practice though a very small litigation practice, but the economics are not good in that kind of relationship. So I recruited Steve Neal, JD ’73, to the firm and we really turned that around and became a leading business litigation firm, as well as corporate.

DAINES You’ve been in a leadership position at Cooley and then as a venture capitalist through a long period of Silicon Valley’s ascent and growth. Have lawyers played a role in the development of Silicon Valley, or just profited from it?

GAITHER Lawyers have played a major role in the development of Silicon Valley. And what differentiates the Valley from other places in the country is that all of the skills necessary to build a company have come together here —legal, accounting, and every other support function you can think of. So you can build a company in a hurry and build it well. What was different on the legal side was that while we were helping them build companies, there wasn’t a hell of a lot of law involved. It was thinking through the challenges that you faced—how to incorporate a company, how to motivate employees, the stock plans, the multiple classes of stock. And all the incentive programs—how do you recruit and motivate people, how do you deal with theft of technology, all that kind of stuff. All of that was created here. And we would go up against New York lawyers and they’d have to send five people who had been exposed to what I had been exposed to because I had done everything. So, there is no question that lawyers played a major role in helping companies address their challenges.

DAINES Looking back, what do you think is the key ingredient to a successful new company?

GAITHER You know, if you want to succeed in the venture capital business, just find great leaders. If you take any venture capital firm going back 50 years, that’s the one criterion that is almost certain to make a difference. It’s leadership; it isn’t technology alone. Growth of market is really important, but not without great leaders. Almost all of the companies have hit walls and the good leaders figure out how to get around them. You know, it’s really important, for example, if there is a patent battle and somebody is going to try to put you out of business. Well, how to deal with that is a very tough, strategic question. And that’s what good general counsels do: figure out how the hell to deal with that. The answer is not to tough it out, as Theranos tried, but to figure out how to address the problem. I remember one case where it was really about how you defined the patent that ensured success against one of the majors that had patents in a related field. So, it’s things like that. How do you turn around people who think you’ve stolen everything? I remember going to a bunch of people and saying, “Look, we didn’t steal it, but if you want to invest, come on in and invest. There’s no need for us to fight about it. Come along with us.”

These things are true today. Lawyers, at their best, are really good problem solvers and that is the skill that I think I got out of Stanford Law School and it really has dominated my life.

DAINES Can you talk about leaving Cooley? Why did you leave and what were you hoping to accomplish?

GAITHER I always said that I wanted to get out of there before the phone stopped ringing, and at the time my definition of that was kind of before I hit 60.

Anyway, I couldn’t leave the firm. I had too big a part of the practice and, until 1999, there just was never a chance when I could pull out without doing real damage to the firm, so I never really considered it. And then the world went crazy and we had about 75 IPOs and 50 mergers going simultaneously. We were probably 300 lawyers short. But it was the first time when I could gracefully leave, and I was doing a reorganization of Sutter Hill and the partners said, “Why don’t you come down and join us?” It was the perfect time. I could do that without anyone at Cooley getting mad at me, and without hurting the business at all. So that’s what I did.

To be honest with you, I don’t think I’m worth a damn as a venture capitalist, but it’s been a terrific time to be on the principal side of transactions, instead of the service side. I’ve done a lot of board stuff and I’ve continued to do that. It’s been a terrific move for me. They’re a very nice and extremely talented bunch of people to work with and all of services—accounting and tax and everything—it’s basically a big family office, so it makes for a very nice business and personal situation.

DAINES Your track record suggests you may actually be worth quite a lot as a venture capitalist. What do you think you bring to the table?

GAITHER The answer is that I think I’m pretty good about judging people and very good at helping them build their businesses. Unlike the person who starts a company from scratch and sees the market opportunities and the strategic value— that’s not me. People and helping them build their businesses and solving their problems is. I think, if I bring anything to the table, that’s what it is.

DAINES I get a lot of students who come to Silicon Valley and catch the bug and decide they want to go into venture capital or private equity. Do you have any advice for law students who want to get into this field?

GAITHER My advice to someone who wants to crack it is to look at the law firms that are active in the emerging company field—there are not many of them—and try to get involved in the early-stage company work. Trying to help these companies is really fun and it gives young people a chance to learn a lot in a hurry. You learn not just a specialty, but you really do learn the role of a general counsel, which is quite a lot of fun—always changing. When you are good at it, it is not long before companies ask you to join them and occasionally venture capital firms do so as well.

DAINES Do you think Silicon Valley will be able to preserve its special place in the world? There is a lot of competition.

GAITHER Absolutely. My guess is that there’s no place in the world quite like it. We’ve all thought, “Oh my God, it’s going to go to Phoenix, San Diego, or Boston,” but it’s going to be a long time. There’s just too much power here. Intellectual power. The young people with great ideas and ambition just keep pouring in. I don’t think the Valley’s in for trouble except for political trouble emanating in Washington, D.C.