One Student’s Experience With the First Ghana Clinic

When I first heard that the law school was offering a clinical program in Ghana for J-term, I jumped at the chance to put my legal knowledge to work in a place that direly needed this help.

The clinic offered two projects that involved working with locally based Ghanaian non-governmental organizations (NGOs): one working with the Center for Public Interest Law (CEPIL) on detainee prisoner rights, the other with the Legal Resources Center (LRC) to organize legal rights workshops for community education. I worked on the detainee prisoner rights project with CEPIL.

Before leaving for Ghana, the school prepared us academically, practically, and mentally. The best instruction came in the form of Dominic Ayine, the director of CEPIL, who was fortuitously earning his JSD at Stanford Law School at the time, allowing him to teach us about Ghanaian legal culture in the comfort of our Aeron chairs. Our work would support CEPIL’s Access to Justice Project, which aimed to address the lack of due process rights for most civilians and the subsequent severe congestion of Ghanaian jails and prisons.

Meeting the prisoners

But even Dominic could not fully prepare us for what we were to witness in the jails of Accra, the capital of this impoverished country. I soon learned the depth of the problem: There are an estimated 12,700 prisoners in Ghanaian jails, of whom 3,500 are remand prisoners, and certain Ghanaian laws (such as the one requiring release of a detainee if he is not brought before a judge within 48 hours) exist only on the books.

With only three weeks to do our work, we eagerly began by meeting with a prison warden, the head of the police, and locally based human rights advocacy groups. What we heard foreshadowed what we would soon see. The head of police told us, “Arrest is the beginning of imprisonment and restriction of liberty, so the idea of any freedom for a suspect does not exist.”

We prepared to meet prisoners by developing a standardized questionnaire for detainee intake interviews. Armed with the heavy artillery of paper and pen, we followed CEPIL lawyers Poku Adusei and James Agalga to the Accra Central Police Station. But whatever defendant and prisoner rights we expected, as is standard in the American criminal justice system, were nowhere in sight. We interviewed detainees, four at a time, in a small room within a short 30- to 45-minute time span— always under the close supervision of police who hovered over our shoulders, “translating” for the detainees.

Dire prison conditions

Nothing could prepare us for what we saw in the prison, where inmates literally sleep on top of one another in airless, dirty squalor. The detainees we met with frequently cried, looked despondent and were covered from head to toe in rashes and boils from unsanitary conditions.

All of the detainees complained about the lack of plumbing. With little ventilation the heat was insufferable, and with severe overcrowding the detainees had to take turns sleeping on the bare ground. We were told of a special room in which the police would beat suspects to obtain “confessions.” These detainees, most of whom had not been formally charged with a crime, sentenced, or even brought before a judge, had to suffer these horrific conditions. Because they could not make bail, they were forgotten and left to rot inside the jail.

During a tour of the prison, the detainees grabbed our arms, pleading for us to listen as they told their stories: that they didn’t get enough food, that they were sick, that they were innocent, that the police were corrupt and took bribes. We had to cut our visit short to avoid a riot breaking out, as the detainees worked themselves into a frenzy. Later when we toured the castles that had been used to hold slaves before they were sent to the New World, we were struck by the eerie parallel of the dark, cramped dungeons in the castles and the jails.

We left the jails each day feeling overwhelmed by the task before us; we knew we could help but a few detainees. And the police controlled the process—deciding which detainees we would interview, leaving us unsure that we saw those most in need of our help. We were driven by our faith in CEPIL and our belief that what we were doing would help reinforce the idea of the rule of law and the importance of human rights for all Ghanaians. During the three weeks that we worked with CEPIL we interviewed 40 detainees, and our research is part of an ongoing project that CEPIL has undertaken in Ghana—work that we hope will result in concrete changes there and elsewhere.

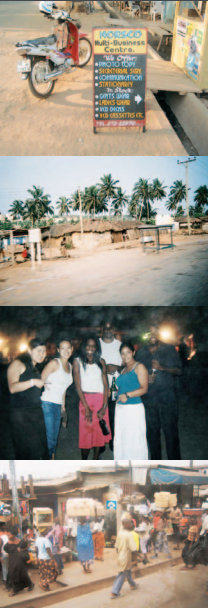

We left Ghana no closer to solving its detainee problem, but perhaps a little wiser and a little more prepared for our legal careers. My resolve to use my law degree to benefit the lives of those in need is now stronger than ever. The experience in the Ghana Clinic was eye-opening, personally as much as professionally, and snapshots of the people I met there will remain with me for a long time.

The Ghana Clinic: An Overview

In January 2006, Stanford Law School clinical instructors Danielle Jones and Peter Reid accompanied eight Stanford law students on a three-week trip to Ghana, West Africa, as part of a new, international clinical program. Each student was assigned to one of two lawyering projects in Ghana with a non-governmental organization (NGO) partner. The clinical work exposed students to unique learning opportunities, where they were able to practice fundamental lawyering skills (e.g., interviewing, legal analysis, drafting, and counseling) in an extraordinary international context. A pre-trip, semester-long course prepared the students for the trip and the work they would soon immerse themselves in.

The Ghana Clinic focused on two project placements with local Ghanaian NGOs, one with the Center for Public Interest Law (CEPIL) and the other with the Legal Resources Center (LRC). Both organizations are directed by Ghanaian attorneys and professors of law working at the University of Ghana.

The students working with CEPIL conducted nearly 40 interviews of Ghanaian detainees being held in police detention centers in Accra, Ghana. Students chronicled the conditions they observed and drafted a final report analyzing Ghanaian and international law to be used by CEPIL in furtherance of its Access to Justice Project. The students working with LRC led workshops and assisted eight Ghanaian community-based organizations (CBOs) in creating detailed action plans to help these groups realize their organizational goals. A consistent goal among the eight CBOs was to further human rights in economically disadvantaged areas throughout Ghana. A second Ghana Clinic is planned for spring 2007.