Sandra Day O’Connor: The Making of a Precedent

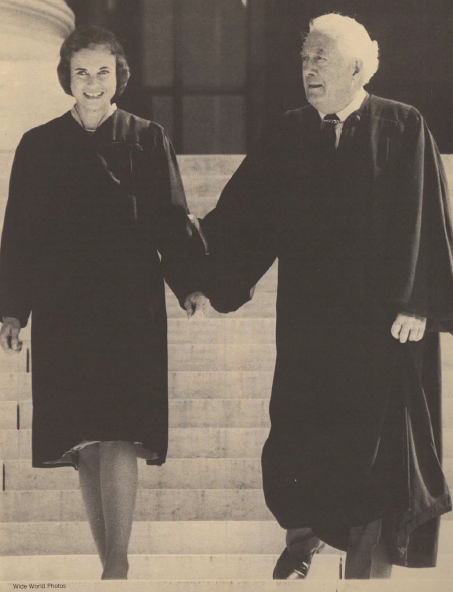

On September 25, 1981, Sandra Day O’Connor raised her hand in Washington, D.C. and, within a few moments, made history as the nation’s 102nd Supreme Court justice and as the first woman ever to sit on the country’s highest tribunal. And at that moment, Stanford Law School became the first law school to seat two members of the same class on the winged bench in the Supreme Court’s colonnaded courtroom.

When President Reagan announced O’Connor’s nomination, he lauded her as “a person for all seasons.” In the days that followed, Reagan’s nominee received enthusiastic endorsement from liberals, moderates, and conservatives alike. Indeed, with the exception of ultra-conservative groups, such as The National Right to Life Committee and The Moral Majority, support for the first female justice was nationwide. An Associated Press-NBC poll revealed that 65% of the country supported O’Connor’s appointment.

When the time came for the Senate to give its crucial assessment, O’Connor was confirmed 99-0. And, with that vote, a 191-year-old tradition was broken; the brethren finally had a sister.

Who is Sandra Day O’Connor? What unique set of experiences and circumstances guided her walk into history? What will her appointment mean for the Court?

Shortly after O’Connor’s nomination was announced a Presidential aide involved in the search for the first woman justice observed: “She [O’Connor] really made it easy. She was the right age, had the right philosophy, the right combination of experience, the right political affiliation, the right backing. She just stood out among the women.”

Indeed, an examination of Sandra O’Connor’s record and career discloses an individual with such impeccable credentials and such an amazing background that one can scarcely believe a single person accomplished it all.

Descended from pioneers, O’Connor grew up on the Lazy B, a 260-square-mile cattle ranch on the Arizona-New Mexico border. As a child, she learned to drive a tractor, ride horses, rope steers, and repair windmills. Life on the isolated ranch, O’Connor has observed, taught her to be “very self-sufficient.” O’Connor showed an early brilliance that prompted her parents to send her off to her grandmother’s home in El Paso, Texas, in search of better urban schools.

The Stanford Years

After attending a private school, O’Connor confidently applied to one college, Stanford, at age sixteen. Despite stiff competition and lacking an entrance exam which her school had forgotten to administer, O’Connor was accepted on the strength of her high marks and many extracurricular activities.

At that time Stanford was attracting ex-servicemen eager to take advantage of the GI bill. As one of O’Connor’s classmates has noted, the Gls, who brought the average age of the class up to 22, “wanted to get on with their lives, and they took education very seriously.”

O’Connor sailed through her courses, neatly completing the economics program in three years and collecting a degree (with great distinction), presidency of her dorm membership in Cap and Gown, and the plaudits of her friends.

“The thing I remember most about her,” recall Atherton Phleger, “aside from her brilliance, was that you never thought of her as a woman because she never isolated herself in that way. She was a complete person, interested in everything and not cloistered.”

Another classmate, Mary Howarth, remembers her to be “so poised, you never thought of her as being younger.” Others have noted that “not only was she bright but she was lots of fun.”

Having completed her economics program one year early, O’Connor applied to the Law School and was accepted under the 3-3 program, whereby the first year of law school also counted as the last year of college. To go to law school in 1950, at a time when many law schools, including Harvard, did not accept women, was something of a fear in itself. Though alumnae agree that there was no post-admission distinction made between men and women, the School was a rough place in those days. One-third of each entering class flunked out.

Beatrice Challiss Laws ’52 recalls that both O’Connor and she studied very hard the first year, “concerned that we might be rolled out. But O’Connor’s roommate, Catherine Lockridge Lee ’53, notes, “Sandra always managed her time so she could go out socially as well as get all her work done.”

Other classmates remember O’Connor as “brilliant” and “endowed with a comfortable, quiet strength.” Emeritus Law Professor John B. Hurlbut, who came to know O’Connor quite well while she was a student, speaks warmly of her: “I have a very high opinion of her intellectual capacities … I am delighted with her appointment because I feel she is well qualified to serve on the Court.”

O’Connor eventually made Order of the Coif and secured a post as one of the revising editors of the Stanford Law Review. There she met John O’Connor, who was a year behind her. They dated for the next 41 consecutive nights. This notable achievement eventually culminated in their marriage shortly after her graduation.

The Early Years in Law

With a law degree in hand, O’Connor interviewed with San Francisco and Los Angeles firms but, as she has explained it, “none had ever hired a woman before as a lawyer, and they were not prepared to do so.”

O’Connor finally located a job as a law clerk with San Marco County District Attorney Keith Sorenson. Later, promoted to deputy district attorney, she worked on civil cases, advising county officials on government codes.

Although O’Connor worked only briefly for Sorenson, he remembers her quite well. He notes that she “was exceptionally bright, very quick at catching on to questions to be researched … her legal writing was exceptionally good. I tried to convince her to stay.”

San Marco attorney James Parmelee worked in the District Attorney Office with O’Connor. He remembers her as “knowledgeable, intelligent, and a great attorney.” Another former colleague from that office is Associate Justice Allison Rouse of the California Court of Appeals. “She was bright and had a great sense of humor,” Rouse recalls.

Following John O’Connor’s graduation in 1953, the couple spent three years in Germany, he with the Judge Advocate General’s staff, and she as a civilian lawyer with the Quartermaster’s Corps.

Establishing Roots

In 1957, the O’Connors moved to Arizona, where John joined the Phoenix firm of Fennemore, Craig, von Ammon & Udall*, and Sandra worked briefly as a part-time suburban lawyer before settling down to five years as a full-time housewife. During this period, their three children, Scott, 24, Brian, 21, and Jay, 19, were born.

While raising her family, Sandra became involved in a number of social concerns, serving as president of the Junior League, an adviser for the Salvation Army, a volunteer at a minority school, and, most recently, a member of the board of the Smithsonian Associates.

O’Connor was also one of the few non-academics ever to serve on the Arizona panel of the American Council of Education, which seeks out and promotes women to college administrative posts. “We thought so highly of her in terms of her support for women that we invited her to sit on the panel, ” explains Sarah Dingham, panel coordinator and a professor at the University of Arizona.

ln addition to their various state and community affiliations, the O’Connors continued to maintain strong ties with Stanford. John, well-known for his ready wit and unflagging enthusiasm, served for four years on the executive committee of the Law School’s Board of Visitors and is currently serving his second year as president of the Law Fund. Sandra served on the University’s Board of Trustees from 1976 to 1980. William Kimball, current president of the Board, remembers Sandra’s tenure on the board: “Whenever she spoke, we all listened. She was a super person.”

Two of the O’Connor children have continued the Stanford tradition. Scott graduated from the University in 1979, and Jay is presently enrolled as a sophomore.

In their private lives, the O’Connors have exhibited the same commitment to perfection that typifies their public activities. When building their home in Paradise Valley, for example, both Sandra and John helped prepare the adobe by soaking the bricks in skimmed milk, an old preparation process. Friend have described Sandra’s cooking as “gourmet,” and have marveled at John’s seemingly boundless repertoire of anecdotes and jokes. Former Dean Charles J. Meyers once applauded their two-step as “almost professional.”

*On January 1, 1982, John O’Connor became a partner at Miller & Chevalier, a Washington, D.C. firm specializing in federal tax matters.

From Homemaker to Legislator

But brick-making and dancing, however finely done, were not enough to fill Sandra’s life. In 1965, when her youngest son went off to school, Sandra decided she “needed a paid job so life would be more orderly.” She joined the Arizona attorney general’s staff.

She also became active in Republican politics and, in 1969, the Maricopa Country Board of Supervisors appointed her to fill a vacancy in the state senate. She was elected to the seat in 1970 and again in 1972. That same year, O’Connor’s Republican colleagues elected her Majority Leader, making her the first female senate majority leader in the United States.

Bill Jacquin, head of the Arizona Chamber of Commerce, was president of the senate when O’Connor was elected majority leader. He supported her for that post because she possesses all the attributes––she does her homework, she knows how to get the proper things out of her staff.”

Her colleagues were not alone in noticing O’Connor’s talents. ln 1971 Dickson Hartwell of Phoenix magazine commented, “It’s doubtful if any fledgling legislator in Arizona’s history contributed as much to key legislation a Mrs. O’Connor.”

Her work in the senate included support of bills to remove sex-based references from state laws, to expand the number of positions open to women by removing outdated job restrictions, and to reform husband-biased community property laws. Also to her credit: antipollution and water control management legislation; maverick support for Medicaid, a program which Arizona alone out of the fifty states did not endorse; virtually solo opposition to state aid to private schools; support of a bill to reinstate the death penalty and of bills compelling open meetings for public agencies and reviews for mental institution inmates.

Her achievements brought the rueful admiration of her opponents. Democratic Senator Alfredo Gutierrez once commented, “She worked interminable hours and read everything there was …. It was impossible to win with her. We’d go to the floor with a few facts and let rhetoric do the rest. Not Sandy. She would overwhelm you with her knowledge.” He called her legislative record “a very activist civil rights record.”

Her Years on the Bench

Her name was mentioned often as a potential Republican candidate for governor, but O’Connor rejected further legislative or executive offices and returned to the law, which she has called “marvelous because it is always changing.”

O’Connor was elected to the Maricopa County Superior Court in 1975, where she remained until Governor Bruce Babbitt appointed her to the state court of appeals in 1979.

On the bench, O’Connor earned the reputation for tough-minded fairness and strict literalism. She also earned the respect of those who argued before her. Phoenix attorney Alice Bendheim recalls: “O’Connor was tough on plaintiffs in personal injury cases. She was hell on lawyers who weren’t prepared. And you had to say something awfully funny to get her to smile on the bench. But I liked her courtroom because you were always treated with dignity there. You always got a fair shake.”

In the 1980 Arizona Bar judicial poll, she scored well in all areas except judicial temperament and courtesy to litigants and lawyers. Her low scores in these areas probably stem from a perfectionist’s impatience with incompetence: on one occasion she advised a litigant to switch to a better-prepared lawyer.

O’Connor, who referred to her occupation in an alumni questionnaire a “administering old fashioned justice in a modern age,’ did occasionally tend toward rough sentencing. She imposed the death penalty on 23-year-old Mark Koch, a convicted hit man. Upon appeal, a new trial was ordered for Koch. However, former Maricopa County Public Defender John Foreman found O’Connor to be “flexible and fair.” He cited one case in which O’Connor sentenced a defendant convicted of possession of heroin and stolen property to five years’ probation. The young man is now in college with a steady job.

O’Connor also gave a minimum term to a bartered wife convicted in a jury trial of murdering her husband. After sentencing, O’Connor wrote to the governor urging clemency for the defendant.

As an appellate judge, O’Connor was “pretty careful and thoughtful,” according to former colleague Judge Donald Froeb. While the 29 opinions she wrote on the appellate bench do nor approach the intellectual and philosophical heights she will be expected to explore on the Supreme Court, the consensus is that they are scholarly and lucid, and they show considerable deference to trial judges, a principle O’Connor espouses in an article she wrote for the Summer 1981 issue of Volume 22 of the William and Mary Law Review. In the article she states, “lt is a step in the right direction to defer to state courts and give finality to their judgments on federal constitutional questions where a full and fair adjudication has been given in the state court …. We should allow the state courts to rule first on the constitutionality of state statutes.” She calls for continued efforts to improve judicial selection and training processes so that federal and state judicial “parity will become less a myth and more a reality.”

Justice O’Connor

What effect Sandra O’Connor will have on the Supreme Court can only remain conjecture for the present. In the storm of approval that followed her nomination, feminists cheered the choice; politicians rejoiced in a candidate acceptable to almost all political persuasions; lawyers admired her intelligence and legal acumen.

Ultra-right conservatives, however, accused President Reagan of breaking a campaign promise by appointing a “pro-abortionist.” They also criticized O’Connor for being against tuition tax credits (O’Connor has been a trustee for private schools) having sponsored the Equal Rights Amendment, and being in favor of no-fault divorce.

Plaudits came from the Court––where Chief Justice Warren Burger and Justice William Rehnquist gave warm endorsements––and from law schools. Harvard’s Laurence Tribe observed, “She’s entirely competent, a nominee of potentially great distinction.” Yale Law Professor Paul Gerwitz called her “smart, fair, self-confident and altogether at home with technical legal issues.” Stanford’s Gerald Gunther rejoiced that the Reagan administration had “taken the high road in filling the Supreme Court vacancy.”

Few people expect O’Connor to produce drastic changes in the Court. Like Justice Porter Stewart, her predecessor, she is likely to remain among the five on the Court who are not completely committed to any political persuasion.

Her legal abilities aside, O’Connor is certain to have other effects on the Court. Her warmth may reduce the somewhat chilly atmosphere and the tendency to be, as Justice Lewis Powell put it, “nine one-man law firms.” Most importantly, every case and issue will now be subjected to a woman’s perspective.

As her close friend, Sharon Rockefeller, wife of West Virginia Governor John D. Rockefeller IV, has observed: “She [O’Connor] understands very well the conflict between a woman’s desire to be part of the professional world and yet to be a perfect mother and wife as well. … If anyone was born to be a judge, Sandra was.” So it would appear that if anyone can handle the challenge of being the first woman on the Supreme Court, Sandra O’Connor can.

The background of a Supreme Court nominee has sometimes proven to be a poor predictor of how that justice would vote on landmark cases. Though it may be years before Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor can be classed with individual colleagues and predecessors all indications are that the wait will not be disappointing.

Sandra O’Connor Day at the Law School

October 5, Sandra O’Connor ‘s first day as a justice of the United States Supreme Court, was officially proclaimed a day of celebration at the Law School.

Students, faculty, and staff commemorated the event by wearing a ribbon and by contributing to a new library fund established in Justice O’Connor’s name. The fund will be used to purchase books relating to the Supreme Court. In a letter addressed, “To The Students of Stanford Law School,” Justice O’Connor expressed her appreciation and hailed the event as “one of the most touching” of the tributes she had received. She added,

“The Law School was such a joy to me (except possibly during Dead Week). I marveled at the talents of my great professors including John Hurlbut, Lowell Turrentine, and Marion Rice Kirkwood. I developed some of the closest friends I will ever have . .. . I crammed for finals at the end of my first year with my good friend, Bill Rehnquist, next to whom I now sit and whose chambers are next to mine. I met my husband on a Stanford Law Review assignment (beware of proof reading over a glass of beer). Beyond those personal relationships, my opportunities for service as an assistant attorney general, as a state senator and as a judge all flowed from the school you now attend. Thus it was in this context of my indebtedness to the Law School that I received notice of your tribute.”

Students responsible for the celebration included Henry Barry ’83 , Kenia Duffy ’82, Lourdes Hernandez ’84, Robert Riggs ’82, and Diana VanEtten ’82.

Sandra’s Day in Court

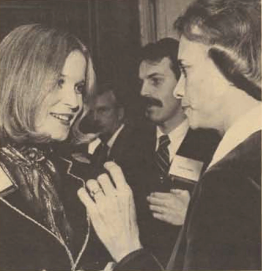

On November 17, more than 400 University and Law School alumni and friends attended a reception for Associate Justice O’Connor at the Supreme Court Building.

Kendyl K. Monroe ’60

Stanford University President Donald Kennedy proclaimed the occasion “Stanford’s day in Court.” Recalling his association with the Justice when she was a member of the Board of Trustees and he was Vice President and Provost, Kennedy said, “No one could be more confident than those of us who have known her work for Stanford that she will bring extraordinary personal qualities to the vital work of this Court.”

Kennedy also credited Stanford’s long tradition of providing women with equal access to higher education––a tradition established in 1895––for the many “firsts” Stanford women have to their credit. He added, “The first woman career ambassador in the United States Foreign Service was a Stanford woman. So with the first woman to serve as Secretary of HUD, and the first woman to serve as Secretary of Education.”

“The message is,” he continued, ”that we are proud of Sandra O’Connor whose own accomplishments brought you here; but proud too that we provided an atmosphere and perhaps a set of values that gave her encouragement.”

Speaking for the Law School, Acting Dean J. Keith Mann praised “the wisdom and prudence displayed by the nomination and confirmation of one of appropriate legal competence, intellect, virtue, and hard-working potential to this Supreme Court of the United States.”

longtime friend and University Trustee,

Sharon Percy Rockefeller

He added, “Cheers to you and for you, Sandra …. This Stanford community is meaningful to you and to us. Wherever you may be, even behind the brass gates here, you can never really leave it. You have given us, and now the nation, the treasure of yourself. I presume to thank you on behalf of us all because it is a gift shared by us all.”

Susan Mann spent the summer as an editorial assistant in the Office of Publications at the Law School. She is currently enrolled as a junior at Bryn Mawr. Dan Fiduccia is a Bay Area freelance journalist. He received his B.A. from Stanford in 1979, and has worked as a publishing assistant to attorneys.