Stanford Community Law Clinic Representing Those in Need

ROSA KNEW SHE WAS BEING CHEATED OUT OF WAGES. AFTER BEING FIRED FROM A SMALL GROCERY IN REDWOOD CITY, Rosa, a pseudonym, did something that would help prove her case: She photocopied a stack of her timecards before leaving the grocery for good. The second thing Rosa did certainly influenced the outcome of her claim: She took it to Larisa Bowman ’09 and the Stanford Community Law Clinic in East Palo Alto.

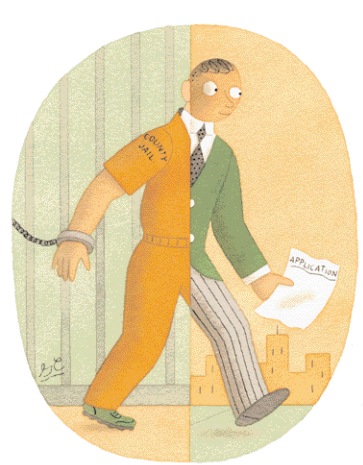

This wage and hours case typifies the many taken on by the clinic each year—ordinary citizens versus the employer or landlord. The clinic practices in three areas: wages and hour enforcement, landlord-tenant, and criminal expungement. Bowman won this one, having spent countless hours poring over the employer’s records and her client’s photocopies. Bowman filed the case in the state enforcement agency, where the official immediately saw that the employer had tampered with the records. A substantial settlement was negotiated on the spot.

Established to provide legal services to low-income residents of the area surrounding the law school, the Stanford Community Law Clinic (SCLC) is one of the few, often only, legal services options available. Its storefront home is busy with a steady flow of potential clients seeking help as they veer into the often intimidating world of courts and legal notices.

Little Case Model “I am very committed to the ‘little case’ model of clinical education,” says Juliet Brodie, who joined the law school faculty in 2006 as an associate professor of law and SCLC’s new director. “We chose our three practice areas because they give rise to cases that tend to be manageable for students, and that move quickly.” While the clinic also gets involved in policy-level projects—Chris Kramer, JD/MBA ’08, and Brodie have been working on behalf of a client this legislative session on a workers’ rights bill—the legal services cases are the “bread and butter” of the practice.

With a constant flow of cases, there’s opportunity. Students sharpen their legal skills on an average of six cases (per student) each semester, taking them from the initial interview through to litigation and negotiation—often within a matter of weeks.

“This was my third hearing and by now I feel like an old hand,” says Mark T. Finucane ’09, who has already secured three successful judgments for clients just two months into the spring semester. While the work done at SCLC is fast-paced, he explains, the first step of meeting the client is crucial.

“People often come to us in a state of extreme anxiety and part of our counseling job is to give them the confidence they need to assert their rights,” says Finucane. “Everything becomes less scary if you have somebody you can trust to explain your rights and to defend you in court.”

Brodie has put her 10 years of clinical legal education experience to work—expanding the reach of this important training ground with the addition of eviction work, or “unlawful detainer” cases as they are called in California.

“No one was doing unlawful detainer work, so we saw a need in the community for this kind of representation,” says Brodie, who before joining the Stanford Law faculty was an assistant attorney general for the state of Wisconsin and then an associate clinical professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School.

Learning by Doing Students are responsible for their individual client cases from intake through disposition. And while they are supervised by Brodie, along with law school lecturer Danielle Jones, and (current) Jay M. Spears Fellow Jessica Steinberg ’04—they are given a lot of leeway as they work their way through their first real lawyering experiences.

Bowman observes that the faculty typically answer students’ questions with a question: “What do you think is the best way to handle this?” Though sometimes answering that question requires more than legal skills. Bowman, who hopes to be a “new take of an old-school poverty lawyer,” describes one recent eviction case as particularly challenging because of the client’s undiagnosed mental illness. “I didn’t see the world in the way that she did,” says Bowman. “But I’ve learned so much from her.” The case highlighted issues specific to dealing with clients who are struggling with the stresses of poverty and illness. But the reward of representing clients in need is clear.

“SCLC offers the chance to do very real work for real people with real problems,” says Finucane. “If the housing client we represented hadn’t found a lawyer, she and her son would almost certainly have been homeless.”