Stanford Law School 1893-1907: from Toulumne’s Peer To Respectability

In the spirit of the Bicentennial, Stanford Lawyer offers this brief look back to the founding of the Stanford Law School.

As a young lawyer in San Francisco many years ago, I once asked an eminent city lawyer what school he had attended. He looked at me and said: “I went to Toulumne Law School. We didn’t have any of these professors out here but whenever I went into a court and a point was raised I didn’t understand, I would pick up my inkstand and throw it at the opposing lawyer. The judge would lock me up 24 hours for contempt and while in such confinement, I would study up the point and be ready for that lawyer.

––W.S. BARNES, SAN FRANCISCO DISTRICT ATTORNEY IN A LECTURE AT THE STANFORD LAW SCHOOL, SEPTEMBER 28, 1894.

“Toulumne” law school training for lawyers in the 19th century was the rule rather than the exception. Until the second decade of the 19th century, training for the practice of law was almost entirely restricted to apprenticeship. Since apprenticeships were long, ranging up to ten years, and the number of apprentices a lawyer could handle was severely limited (usually about two), the profession grew slowly in numbers. As the population of the U.S. increased, the demand for legal services outstripped supply.

This increased demand for legal services fostered the growth of formal legal education in universities. Most of the law schools established during this period were not actually “schools,” but regular university departments that offered a law “major.” Requirements for admission were ordinarily only those exacted for admission to the freshman class of the college. This was true in 43 of the 61 universities offering law training in 1890. Even when the Association of American Law Schools was organized in 1900 it decided that its members need require only a high school education for admission. Instruction during this period was normally based on lectures used to supplement and illuminate assigned textbook reading.

By the time Stanford began offering instruction in law in 1893, the trend toward modern law schools was under way. Harvard was the center of innovation, with the publication of Langdell’s casebook in 1871. Moreover, in 1878 Harvard began requiring three years of graduate study, though only two had to be spent in residence, with the third year checked by examination.

Law school admission and graduation requirements reflected then, as they do now, the standards set by the state bars and legal community. Until 1909 there were virtually no California Bar admission requirements. It was very common for students to have a pre-legal curriculum, take one year of law, get their A.B. degrees, and go into practice. Since there was no committee of bar examiners, admission to the Bar was by action of the appellate courts. No written examination was given and standard procedure was to take a group of 35 to 40 aspiring lawyers into a room, ask each one a few questions, and, if he answered them satisfactorily, he was admitted.

The following letter to Judge Samuel F. Lieb, first president of the Board of Trustees of the University, from a graduate of the Law Department depicts a typical bar examination in the early 1900s.

Dear Sir:

Thinking it may interest you to hear how the recent examination of the applicants for the admition (sic) to the bar was conducted I take the liberty to give you a brief report thereof. There were about forty applicants, but only twenty five were successful. I have the great pleasure to announce that I am one of them. My examination was exceptionally brief, presumably on account of your endorsement on my application blank. They asked me no more than fifteen questions on criminal law, which I promptly answered.

The whole examination was very rigid, covering the entire field of Jurisprudence. It took them fully two hours to examine a class of ten applicants. The questions were fair, practical legal questions, such as a student is accustomed to learn in a class recitation, or in a good textbook.

I write this with the deepest gratitude to you as the president of the board of trustees of our university for attaching your honorable name to my application, and secondly, as a Stanford student, inspired by the Stanford Spirit, I am endeavoring hereby to express my honor and appreciation of the noble and great “STANFORD”, a name that will perpetually sound in my heart with love and praise for the benefit that I received in this great institution.

Whatever my carrier (sic) may be in the future, whether successful or not successful, pleasant or gloomy, or no matter what condition l shall occupy, it will always be my earnest endeavor to live for the honor of the Stanford Spirit, and as a member of the legal profession, try to make the truth visible, as Dr. Abbott has taught me.

I remain Yours, very respectfully,

Frederick May

Though bar standards were weak, practicing law was not an easy way to get rich quick. Justice Myrick of the California Supreme Court warned his Stanford law student audience in a speech before them in 1898 that” In the legitimate practice of law, you will probably never accumulate a fortune.” Worried that he would quickly lose his audience to Klondike gold fields, he hastened to add that “you can make a good living and more, you can attain an honorable place in the world.” He did not warn his audience about the regional differences in fee “schedules,” however. A few months later, a Stanford law graduate, Carl Smith, ruefully explained in the Daily Palo Alto that such a difference existed between California and Hawaii. Smith defended a man accused of selling liquor. After clearing his client on a technicality, he did not know what to charge him, and sought the advice of a Japanese interpreter. Smith suggested $10 to the interpreter who exclaimed “holy smokes.” Smith blanched and said he would make it only five. Only later did he discover that $100 would have been a low fee.

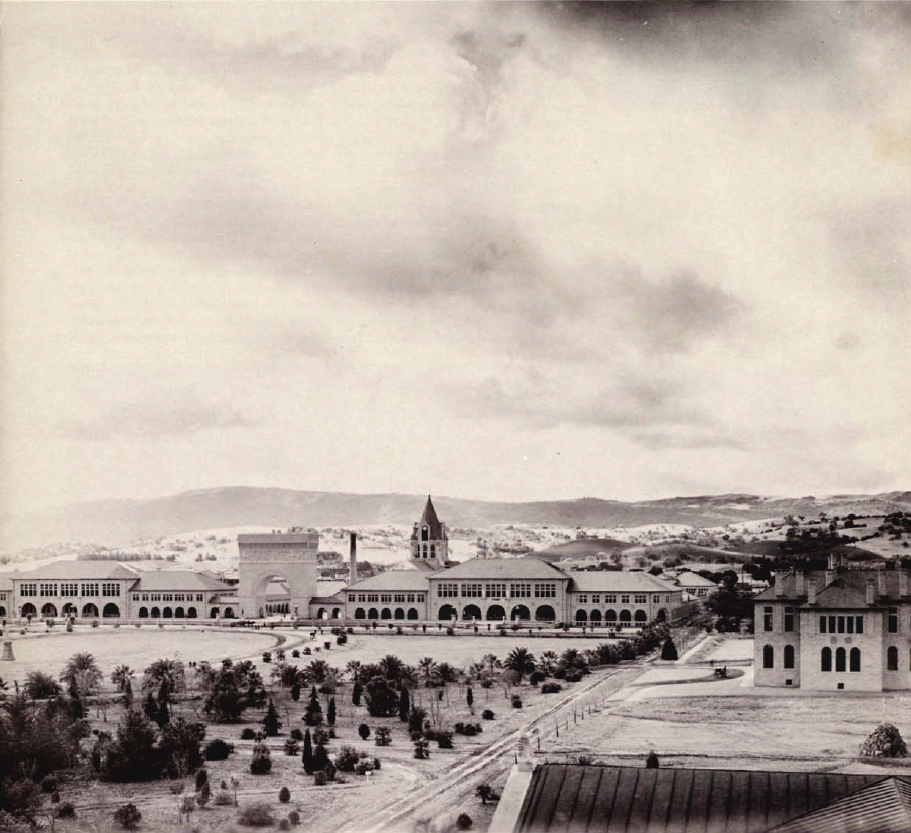

Stanford University was founded in 1891. A year later, President David Starr Jordan began serious planning of a law department. He traveled to Chicago to consult with Professors Ernest Huffcutt and Nathan Abbott at Northwestern, two nationally recognized law professors. Jordan’s hope was to secure two or three “name” professors and build from there. He and the Stanfords favored a shortened, pragmatic approach to education which would turn out self-supporting individuals in the shortest possible time. Jordan’s law school curriculum plan was somewhat of a compromise between the then fashionable undergraduate law degree, and the more rigorous Harvard Law School graduate program. The plan called for the distribution of courses over a five-year period beginning with the sophomore year and continuing for two years after graduation from college. The junior and senior years would contain the normal graduate law school first-year curriculum. On graduation, the law major would receive an A.B. in law. He would then enroll in the equivalent of today’s second- and third-year J.D. curriculum and graduate with an LL.B.

Jordan’s plans for recruiting faculty were highly ambitious. He intended to have Professor Huffcutt open the school, to be followed in successive years by Professor Abbott, Professor Melville Bigelow (dean of Cornell’s Law School), Sir Frederick Pollack (Regius Professor of Jurisprudence at Oxford), and finally, Woodrow Wilson, then a professor at Princeton.

Jordan also expected to provide an ample law library. Unfortunately, he was unable to dredge the necessary funds from the fledgling and financially starved University. As a result, Huffcutt rejected the Stanford offer in favor of Cornell, which had just received a gift of the Moak Library. To fill the gap created by Huffcutt’s withdrawal, Jordan asked Abbott to come to Stanford a year early. He also persuaded Benjamin Harrison, President of the U.S. at the time, to come to Stanford after his term ended in 1893, and open the School with a series of lectures on Constitutional Law. Harrison was to be a non-resident professor.

Even these plans had to be shelved after financial disaster swept the University in 1893. Senator Stanford died in June; the great financial panic struck immediately thereafter; and towards the end of the year, the United States sued to establish a claim against the Senator’s estate for $15,237,000, allegedly due under the California stockholders liability law for money loaned by the United States to Senator Stanford’s Central Pacific Railroad Company to aid in the construction of the railway. The panic depleted the value of the assets in the estate and depressed their earnings. The litigation tied up assets retained by the Stanfords after the Founding Grant and only a generous family allowance granted to Mrs. Stanford by an understanding probate judge, which she used for university expenses, and loyal faculty who accepted sharp reductions in salary prevented bankruptcy.

Abbott heard of these developments en route to Stanford. He called Dr. Jordan from St. Paul, Minnesota, asking him whether he should still come. Jordan offered Abbott a year’s leave of absence by return cable and Abbott accepted, apprehensive about the future of the University.

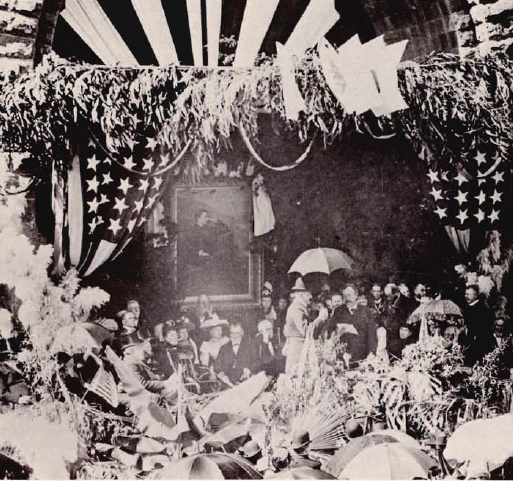

Mrs. Stanford are seated to the left of

the speaker, David Starr Jordan, first

president of the University. A portrait of Leland Stanford, Jr. dominates the scene.

In desperation, Jordan turned to his University Librarian, Edward Woodruff, who had graduated from Cornell Law School in 1888. Woodruff had taught English at Cornell for two years, practiced law only briefly, and was reluctant to accept the assignment. He complained to Jordan that he was too busy as Librarian already, and that he hadn’t opened a law book in four years. Jordan offered Woodruff extra help in the library, however, and coaxed him into accepting the job. Woodruff apparently grew to like his new job, for he continued to teach law until his retirement from the Cornell law faculty in 1926.

Thus, the Stanford law department got off to an austere start. Woodruff taught Elementary Law and Contracts during the first year of its existence. Benjamin Harrison had given his set of lectures the previous spring, focusing on Constitutional Law and the development of the constitutions of the original thirteen colonies. Harrison left shortly afterwards. He did not think too much of the proposed school and especially disapproved of including work for the A.B. degree in credit for the LL.B. degree. He compared this double service to a passage from Oliver Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village: The chest contrived a double debt to pay, A bed at night, a chest of drawers by day.

By 1894, things had begun to settle down at Stanford, and Abbott agreed to assume his position. Though the government suit was not dismissed until 1895 with United States v. Stanford, the financial panic had passed, and the University had managed to achieve fiscal balance.

Abbott was an extraordinary individual. His academic interests were property and the history of property law, which he combined with apparently limitless interests in subjects outside the law and various hobbies. These outside interests included Greek literature and art, membership in the Dickens Society in London (the first American to be so honored), horticulture, carpentry, chamber music, and Abraham Lincoln. He regularly played the cello in a chamber society, and skillfully employed his carpentry talents in building the furniture for the Law School after he arrived, including all the desks and podia. It is likely that he took a substantial income cut to come to Stanford, since he was earning $25,000 a year in Chicago as a consultant to the legal department of a large corporation, in addition to his academic salary.

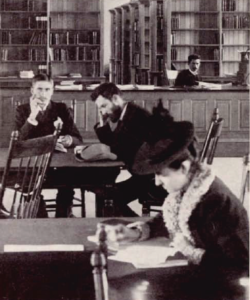

Student interest in the Law Department increased rapidly. In 1894-95, 100 students were enrolled in the Department’s courses, a figure which climbed to 171 by 1899. Abbott faced significant problems in meeting this demand.

To begin with, the Law Department had little space. It occupied three former bedrooms in Encina Hall, a men’s dormitory. One of these was used as a library. In 1900 the department occupied rooms in the northeast corner of the Inner Quadrangle, formerly used by the main library. These rooms were divided into a law library, reading room, three offices and two lecture rooms. In contrast to the 1975 move to Crown Quadrangle, which took professional movers several weeks, this move was completed in one day by the students themselves.

Abbott’s second major problem was the lack of an adequate library. In a letter dated March 3, 1933 Professor Abbott remembers the start of the Stanford Law Library:

The absence of any law books for the use of the students also had its effect on our program… I advised the buying of the American Decisions because of the extensive notes which the students could refer to in the absence of text books which Pres. Jordan did not feel the University could afford to buy. I believe I am correct in saying that before the Decisions were received the Bancroft Whitney Company gave us a set of books called “The Pony Law Series”. I remember making a little book case about fifteen inches long and seven or eight inches high and five inches deep to hold these books. At this time the students had no place in the quadrangle to study and we were given the first room on the left hand (ground floor) of the entrance to Encina Hall. I remember hanging this book shelf, like a picture, on the wall of this little room and it was the beginning of your Law Library.

Abbott’s third and perhaps most difficult task was retaining good faculty. Woodruff left for Cornell in 1896, despite President Jordan’s entreaties. Jordan first wrote him a letter on February 18, 1896, asking him whether he would return to be librarian or law professor but indicating it would be best if he would do both until the money crisis was over. Woodruff demurred and Jordan wrote a letter on March 12 pleading, “Please don’t go-We need you. Only Abbott, Huffcutt and yourself know the Law School I dream of. It will come and great will be the man who brings it.” Two days later he added in a telegram, “Don’t go. Needed here. We offer law professorship exclusively now.” When Woodruff persisted in his refusal, Jordan wrote to Woodruff acknowledging his decision, “As soon as we are rich we shall undoubtedly wish to call some firstclass men to the Law Department such as Huffcutt, Woodruff or Woodrow Wilson. In the meantime, we shall have to be content with temporary supplies.”

Jordan and Abbott’s “temporary supplies” proved to be all too temporary. During the years 1897-1907 the Stanford Law School became a developing ground for promising young law professors who were pirated away by more established law schools. Two of them, Professors James Hall and Clarke Whittier, went to the University of Chicago in 1901. A third, Jackson Eli Reynolds, who had been an undergraduate at Stanford and a great halfback on the football team, went to Columbia in 1901. All of these men were assistant or associate professors at Stanford, and were hired away as full professors. Money as well as prestige was an important factor in their decision. Whittier received only $150 for his teaching in 1897 and some professors in other departments were teaching gratis, because of the University’s financial plight. Those who were paid took a mandatory 10% cut in salary to pay for the defense of the Government suit. When Whittier went to Chicago he was paid $5,500 a year, a considerable improvement over his meager Stanford salary. He also had access to a substantial law library, which was not something Stanford could offer to its faculty before 1903. Until then, faculty had to trek to San Francisco to do their research at the county courthouse library.

Throughout this period, Abbott did a remarkable job keeping together a rather good faculty. His was continually able to make up his losses by hiring promising newcomers. To supplement the regular faculty, which normally numbered between three and five professors, he imported practicing lawyers to teach courses on a part time basis. Some of them, such as Judge Curtis Lindley of San Francisco, who taught Mining and Irrigation Law, had national reputations and had published a considerable amount. In his recollections Whittier noted that the Law School came of age in 1900-01, in spite of the losses of himself and other faculty members shortly afterwards:

The year 1900-01 lived up to the promise of the Register that ‘this department offers such courses in law as are usually given in professional law schools.’ There was a fine spirit in the Department. Mr. Abbott was in his prime and the rest of us were young fellows trying to win a modest place in the sun and enthusiastic about the new Department and its future. The students seemed to think we were a lot of ‘wise guys’ and that before long, Harvard Law School would have to look to its laurels.

In the spring of 1901, the Law Department conferred its first professional degree, the Bachelor of Laws or LL.B., on James Burcham. This degree had been introduced by Harvard in this country and was the chief law degree conferred in 1901, though some schools, like Stanford, also conferred B.A.s. Since by this time many law schools required graduation from college as an admission requirement, it seemed odd to award a second baccalaureate degree. Recognizing this, Stanford changed its degree to a Juris Doctor (J.D.) in 1906, making it analogous to the degrees of M.D. and Ph.D. Harvard retained the LL.B., though other law schools including Chicago and Hastings, joined Stanford and replaced it with a J.D. Stanford resurrected the LL.B. in 1911, abolished it again in 1921, reinstated it in 1927, and finally abolished it again in 1969 in favor of the J.D. It is unclear why the faculty was so whimsical about this issue over the years, but the sequence is a tribute to Abbott’s practice of having the faculty decide major issues by majority vote, a tradition continued to the present.

Few women entered the Department of Law in its formative years, though the University was coeducational from the beginning and, according to Professor Whittier, “The few young women who joined our ranks were not in any separate category from the men. They found their individual places in class work and in records just as so many extra men would. have done.” Though women were an established part of the University, the issue of coeducation was controversial. President Jordan was a firm believer in it. In a forum on the issue in the Daily Palo Alto on October 23, 1901, he suggested that “women educated with men are likely to have sounder ideas of work and a clearer perspective of things as they are than ones educated by or among women only. Men educated with women are likely to develop better personal habits and finer tastes than those who are monastically educated, meeting either no women at all or only on the inferior plane of social functions.”

In contrast, Professor Abbott opposed not only coeducation, but the whole system of higher education for women. In the same forum he stated: “The whole business is a mistake. I do not believe in the modern system of educating women. I think they are over-educated. The tendency is to spoil a good woman to make a poor man our of her.”

The only example of overt discrimination against women during this era was their exclusion from the Law School steps. The steps were at the end of the corridor running in front of the Law School, the side of the Inner Quad that now houses the President’s Office. Jordan strongly opposed the use of tobacco on the quad. In deference to his wishes, students would walk to the steps where they would talk and smoke between classes. As soon as they got out from under the arcade, they figured they were no longer on the Quad. The steps were strictly reserved for law students and fights would occasionally erupt when non-law students attempted to break the tradition. Women law students were not welcome either. They would not be thrown off, but were immediately made to feel unwelcome. The tradition of the Law School steps apparently persisted until the Second World War.

During Abbott’s tenure as department head, several extracurricular clubs and organizations for law students got their start. The Law Student Association was formed in 1904, with James Burcham, the first Stanford LL.B., as president. Moot Court was very popular during this period and several clubs were formed whose principal purpose was oral advocacy and debating. Bench and Bar and the Coif Club were the oldest and most prestigious clubs and a rather intense rivalry existed between them. Each year two representatives of each club argued a case against the other, the prestige of the clubs riding on the outcome. They also played in a baseball game against each other annually. Professor Abbott was always the umpire and was noted for his ability to call all balls strikes, and all strikes balls.

On April 18, 1906, the devastating earthquake hit the Bay Area, destroying much of San Francisco and causing heavy damage to Stanford. The Law Department, being in a one-story building, suffered little physical loss, but along with the rest of the University, it had to face a further period of austerity so that the plant could be restored. The entire University closed temporarily. The Law School suffered an even more crippling blow a month later when Abbott decided to leave Stanford for Columbia, succumbing to the same pressures that he had to fight against to retain his faculty against raids from other law schools. Jackson Eli Reynolds, formerly a professor at Stanford and then at Columbia, was a major influence in Abbott’s decision. Abbott was reluctant to leave, but Reynolds was adamant. In a letter to Abbott on May 29, 1906, he wrote: “If you throw me down on this thing I shall be thoroughly vexed. I’ve set my heart on this connection between you and Columbia and I’ve been working to bring it about ever since I first broached the idea to you. That is all bally flubdub about you not being suited to Columbia and I won’t listen to such nonsense.”

Abbott eventually relented and agreed to take a year’s leave of absence to become a visiting professor at Columbia. Columbia was apparently to his liking, for he never came back. Jordan made a last ditch attempt to coax him back in early 1907. In a letter to Abbott on January 30, 1907, Jordan offered him a raise to $5000, as well as raises for all the other professors and reimbursement for Abbott’s own out-of-pocket expenses incurred in building up the new law school. Abbott demurred and on February 10, 1907, the New York Daily Tribune published news of his resignation: “Stanford University has suffered a serious loss in the removal of Dr. Nathan Abbott to Columbia …. It has been known for some time that he was dissatisfied with conditions at Stanford, especially with the arbitrary action of the faculty last year on suspending one of the best students in Dr. Abbott’s class because, as the editor of the college paper, he criticized the system of faculty espionage in the dormitory.”

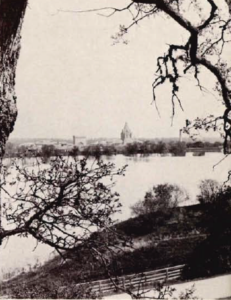

Lake Lagunita

In the thirteen years of his tenure at Stanford, Nathan Abbott left an indelible mark on the School. Perhaps the special qualities of this extraordinary teacher and scholar were best described by Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, Abbott’s former colleague at Columbia Law School, on the occasion of Abbott’s death in 1941:

Withal, intimate association with a man of such colorful personality who never did anything quite as more ordinary mortals do it, broadened the student horizon and added a piquant flavor to student life… . We shall not see his like again.