Stanford Law Students Back From War

Over the past few years the composition of Stanford Law School’s student body has taken on a subtle change not seen since the Vietnam War. Now five years into the Iraq war and seven years since the start of the Afghanistan mission, a new generation of war veterans is attending the law school—fresh from service, many with combat experience. For some of these students, military service was always in their future. For others, the events of 9/11 so moved them that they enlisted. All of them have a unique contribution to make to the layered diversity of Stanford Law School and, ultimately, to the profession. The stories that follow offer a glimpse into the lives of four students and their experiences in the military.

A Military Union: Russ and Sandy Fusco

Ten years ago, Russ and Sandy Fusco’s paths probably wouldn’t have crossed. As fate would have it, they were both commissioned into the Navy out of college in 1997 where they met in flight school while training to be naval flight officers. They were assigned to the same squadron when they deployed together to the Persian Gulf in late 2000—the Navy’s 1993 decision allowing women to fly in combat making it possible. “The Navy just kept throwing us together,” says Russ ’09.

In September 2001 they were stateside training for their next deployment when Al Qaeda struck. Their squadron was immediately redeployed and by November 2001 they were on the USS John C. Stennis headed to the Indian Ocean. This time they flew missions over Afghanistan and the border areas of Pakistan, providing air support for ground troops.

“We were shot at, but they weren’t going to reach our planes,” recalls Russ. “We were trying to get all the way to Afghanistan and back but we couldn’t refuel, so we were flying past our range all the time. There were times I thought, this is it and we won’t make it.”

They were bolstered by the support they felt from folks back home.

“The second deployment was real. It was about protecting our country,” says Sandy ’08. “We were lucky to have so much support from back home. I had letters from kids hung on my wall saying ‘I hope you don’t die’ and ‘I hope you get the terrorists.’ I don’t know that the troops are getting that support now.”

While Russ found the sounds and smells of the Middle East familiar, reminding him of his Syrian grandmother’s kitchen, Sandy was not at home in the male-dominated culture. She remembers being excluded from a detachment to Kuwait simply because she was a woman.

“Russ was welcomed in the Middle East and had a wonderful time,” she says. “I was hyper-aware of my very different status in that part of the world.”

But the overall benefits of her military experience far outweigh any challenges she encountered, according to Sandy. In addition to providing funding for her undergraduate studies at Cornell, the Navy helped to shape who she is today.

“Having served in the military, especially as a young woman in a very male-dominated area, I was able to prove myself,” says Sandy. “Because of that, I don’t face the same issues that I see my younger law school classmates facing. When I deployed on an aircraft carrier and flew missions, I was aware of the fact that what I was doing was special—something that women 10 years earlier were not allowed to do. It was very, very important to me.”

Russ and Sandy served together in the Navy for five years, but it wasn’t until Sandy was about to leave the squadron that the two considered romance.

“I realized toward the end of the deployment that I was really upset about leaving Russ. I couldn’t figure out why I was getting so emotional. He was just one of the guys,” Sandy recalls. They started dating and were married two years later—the weekend after they took their LSATs.

Now well into law school, Russ and Sandy consider themselves fortunate to have each other to share the memories and friendships of Navy life and the challenges of law school—which now include juggling study with parenting their baby. As to how training to fly in the Navy compares with Stanford Law School, they agree that there are some similarities.

“We spent two years in flight training to get to the peak of our abilities—just like law school,” says Russ. “When we graduate, we’ll show up at a firm and be pretty much useless for the first year while we put the theory into practice, which is how it was in the Navy.”

There are some subtle differences, though, they say. You can flunk out of flight school pretty easily—many do. And when you fail an exam in the Navy, everyone knows about it because you’re made to wear your regular khakis rather than a flight suit. But the comraderie they’ve found at Stanford Law School does compare favorably with the Navy: Both experiences are intense and foster strong personal bonds with colleagues.

“It’s interesting for us to see so many military people at the law school now. We were the first wave. There’s a new generation of veterans, so it’s turning into a fairly common experience,” says Russ.

Ordinary Infantryman

Sean Barney We deployed to Fallujah. I was shot through the neck. The bullet actually severed my carotid artery, which ordinarily would mean a matter of seconds and then you’re done. But the very heat of the round ended up cauterizing it.

Sean Barney ’10 was working as a policy advisor to Delaware Senator Thomas Carper in Washington, D.C., in September 2001. He’d studied political science at Swarthmore and caught the political bug while volunteering on Bill Bradley’s 1999 presidential bid. And so he found himself at the center of the nation’s government when the twin towers fell and the Pentagon was hit. The events struck a patriotic chord in Barney—and an idealistic one. By the spring of 2002, he’d made up his mind to enlist in the Marine Corps Reserve. Though not as an officer, but as infantry.

Little did he know that a year later he would be fighting for his life in a Bethesda, Md., hospital.

“My military heroes aren’t generals or even officers who’ve won great battles,” he says. “They’re the 17- or 18-year-old kids from a farm somewhere who had never intended to be in the military. Then WWII came along and they end up in places like Normandy or Iwo Jima. I always admired that commitment to this country, to the democratic process, and to service,” he says.

I remember the sound of the shot, but the thing I don’t remember is being knocked down, as hard as that thing knocks you down. But I got up. It’s an amazing thing about military training the way things just get drilled into you, because it wasn’t a conscious thought process. You get trained to be very aware of your surroundings and whether you have cover and concealment. I knew immediately that I didn’t have either, so whoever had just hit me, I was still in their sights. I remember my body reacting. It’s this experience of your body, like a fire alarm going off. Your body is in crisis. I got up and tried to figure out what direction to move in and it was very weird because my arm was paralyzed.

By the end of 2002, Barney was in boot camp in North Carolina, being made into a Marine.

“In some ways, it’s comparable to the first semester of law school,” he says. “It’s where you get let into the club and where they also impose upon you what’s expected of those who are let in.”

As an infantry Marine, Barney didn’t have much in common with his peers. He was better educated than many of his superiors. But the officer’s experience wasn’t what he was after. And despite their disparate backgrounds, he bonded with the members of his battalion— bonds that were strengthened by the experiences of combat.

“BUT I HAD THIS FEELING WHILE SERVING THAT THE COUNTRY DID NOT TAKE THE DECISION TO INVADE SERIOUSLY, DID NOT HAVE A SERIOUS DEBATE, DID NOT SEARCH ITS SOUL BEFORE GOING TO IRAQ.”

– Sean Barney ’10

He was in training as a machine gunner at Camp Lejeune when the United States invaded Iraq—adding “an extra edge” to the training, as the possibility of fighting became a much more tangible, and looming, reality. By then his sights were already set on Stanford Law School, but he deferred his admission and instead volunteered for a deployment to Iraq.

I thought my arm had been blown off. But I was just looking for the direction in which to move. And this sergeant yells, Barney, over here Barney! So I vaguely discerned the direction and I ran, which in the telling of my platoon mates was more like the rapid, stumbling of a drunken person. I ran about a half city block when I realized I had cover and concealment and within a second or two I lost consciousness.

After two months of patrolling the streets of Fallujah, Barney’s stay was cut short by a sniper’s shot to his neck. Within 48 hours he was in a hospital bed in Bethesda. After three surgeries and a year of convalescing, he was almost back to normal and gearing up for another boot camp—his first year of law school.

He saw the severely wounded in Bethesda, so considers himself lucky to have gotten away with what he calls a minor injury, a partially paralyzed arm. Mostly, he’s thankful that he survived.

At the age of 32, Barney is a bit older than most of his classmates—and certainly more experienced with life and death issues. He’s not sure how he’ll use his JD—but believing the weight of his experiences at war important, he may go into politics and someday perhaps run for elected office.

“It’s necessary to have a military, and it’s necessary to use it every now and then,” says Barney, who was awarded a Purple Heart. “But I had this feeling while serving that the country did not take the decision to invade seriously, did not have a serious debate, did not search its soul before going to Iraq. I think that’s a reflection, in part, of the very, very few veterans in Congress and in public life, proportionately, compared to what it was in the past.”

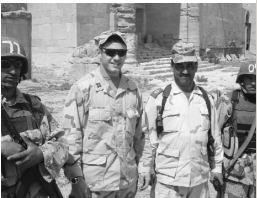

Ryan Southerland: Training Iraqi Officers

Ryan Southerland’s first deployment to Iraq should have been smooth sailing. It was November 2003—just months after the successes of the initial American-led invasion, the toppling of Saddam Hussein, and President Bush’s now famous “mission accomplished” declaration.

“The war talk was pretty rosy,” he says. “But things on the ground were souring quickly.”

Southerland ’10 was in his last year of studies at West Point on September 11, 2001. A hilltop on the historic military campus, located about 50 miles up the Hudson River from Manhattan, provided a safe vantage point onto the smoke-filled city in the aftermath of that day. “The attacks of 9/11 definitely focused our attention. It was an awakening for my whole peer group,” he explains.

Ryan didn’t come from a military family but set his sights on West Point as a way to challenge himself physically and mentally while having a chance to see the world. He graduated in spring 2002 and after a little more than a year of training was ready for combat.

As a second lieutenant and later a captain in the Army Infantry, he led four Stryker vehicles with 42 soldiers. They spent most of the year in the northern city of Mosul, where they patrolled the streets and worked with the Iraqi Police and Iraqi Army to secure the peace.

“I found local Iraqis’ opinions about the war to be as varied and diverse as the opinions of the average American,” he observes. “But they were better informed because they were living it every day.”

When he returned to the states, he found people to be genuinely curious about the larger issues of the war but limited by the political rhetoric.

“I’d come home and my friends and family would ask me ‘are we doing the right thing, are we spreading democracy?’ As if you could spread it like peanut butter,” he recalls.

Southerland volunteered for a second yearlong stint in Iraq in May 2005, this time as a military advisor embedded with the Iraqi Army. He was one of 10 Americans providing training to the Iraqi leaders of a 700-strong battalion. The experience was eye-opening.

“I’D COME HOME AND MY FRIENDS AND FAMILY WOULD ASK ME ‘ARE WE DOING THE RIGHT THING, ARE WE SPREADING DEMOCRACY?’ AS IF YOU COULD SPREAD IT LIKE PEANUT BUTTER.”

– Ryan Southerland ’10

“It certainly drained any remaining optimism that I might have had about achieving the initial goals of the war,” he says, explaining that his largest frustration was not with the Iraqis but with the American military leadership. “We seemed to struggle with getting over our cultural narrow-mindedness. We couldn’t recognize some of the nuances of the situation—like how politics works at the local level, how power is shared and gained and overthrown, and what kept things secure. I didn’t see us making progress.”

Regardless, Southerland says he values his military experience. He also values the relationships he forged with both Americans and Iraqis. One Iraqi officer, Ali, stands out. Ali was an imam and so led prayers for the Islamic soldiers. Southerland recalls joining him once at the brigade’s mosque for evening prayers. Before entering the mosque, Southerland took his shoes—and gun— off and left them outside the door. While they were kneeling down, Southerland felt something on his hip. It was his Iraqi counterpart re-arming him.

“He goes outside, gets my gun, and puts it back in my holster,” Southerland recounts. “I looked at him and he just kind of nodded.”

Now at law school, Southerland is re-adjusting to the focus of studies— keen for the next chapter of his life. “Lawyering has always been a possibility for me,” he says, noting that his grandmother and several aunts and uncles are lawyers. “It offers so many opportunities. Every sector of our society has a legal aspect.”