The Early Years

The study of law at Stanford University is nearly as old as the University itself. In April 1893, a year-and-a-half after opening, the University published the plan, organization, and courses for a Department of Law. And four months later, on September 8, 1893, the first class––Elementary Law––convened in the University chapel.

The new Department represented an innovation in legal education. Rather than set up a separate law school, Stanford President David Starr Jordan decided to establish a law department open to both undergraduate and graduate students.

He had two reasons. First, he wanted to make sure that Stanford-educated lawyers earned at least a bachelor’s degree –– a relative rarity in the profession at the time. Second, he wanted to enable all Stanford students to study the legal system, fulfilling founder Leland Stanford’s wish to “present the fundamental principles of law in such a manner that every student may understand them.”

As the Department of Law matured, it began to concentrate on the professional training of future lawyers, symbolized by its change in name to Stanford Law School in 1908. This photographic essay recalls those initial fifteen years in which the study of law at Stanford took root.

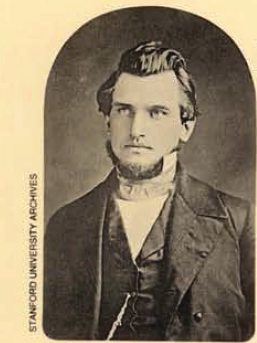

LELAND STANFORD, ESQ.

Though best known as a railroad magnate, politician, and university founder, Leland Stanford’s first profession was law––a calling that greatly influenced his educational philosophy. In 1848, when this daguerreotype was taken, he had just been admitted to the New York Bar. His subsequent career as lawyer, governor, and senator persuaded him of the need to educate young Americans in the legal foundations of democracy. In 1893, while planning the Law Department with President Jordan, Stanford wrote: “We want the people instructed in the law, for with the law rests the science of government.”

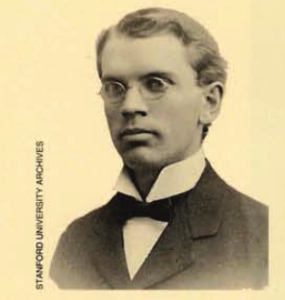

LOOKING FOR A LEADER.

Jordan conducted an extensive search for a professor to head the planned Department. His first offer was to Woodrow Wilson, then a Princeton professor of jurisprudence and a leading advocate of the undergraduate study of law; but Wilson declined. Ernest Huffcutt, a brilliant law professor at Northwestern, did accept tentatively in January 1893 and even drafted the Department’s curriculum in anticipation of its September 1893 opening. But a few weeks later Huffcutt chose Cornell over Stanford and recommended his colleague, Nathan Abbott. On March 6, 1893, Abbott (affectionately caricatured here) accepted Jordan’s offer and became the Department’s founding Head.

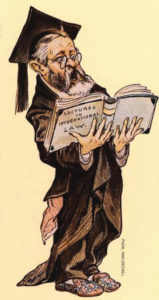

A FAMOUS FIRST.

While Jordan was negotiating with Huffcutt and Abbott, Senator Stanford was persuading an old political ally to join the Department. On March 2, 1893, two days before leaving national office, President Benjamin Harrison accepted his friend’s offer to become a non-resident Professor of Law at Stanford––and the first former President to serve as a professor anywhere.

Senator Stanford boasted that Harrison had “experience, from his position, that no other man has had. His lectures will undoubtedly be very valuable, not only to our students, but to all civilized people.” Cartoonist joseph Keppler took a less exalted view. In the caption beneath this March 22, 1893, cartoon in the humor magazine Puck, Harrison warbles: “Oh, what do I care for a Presidencee? / A Professor’s life is the life for me! / Away out on the far Pacific Coast / The youthful Freshmen will I roast; / And the seals of Alaska shall shiver with awe / When I preach on International Law!” (In fact, Harrison arranged to begin teaching in the spring of 1894 to allow time to prepare innovative lectures on the history of the American Constitution.)

With the appointment of Harrison and Abbott, the first law faculty seemed complete. “I think there will be instruction in … Law,” Leland Stanford wrote triumphantly in his last letter before his death on June 21,1893.

A VIRTUE OF NECESSITY.

When Abbott learned of Senator Stanford’s death, he became so skeptical about the University’s prospects that in August 1893 he requested a year’s leave. The Law Department, scheduled to open in one month, suddenly had no professor! Jordan asked the University Librarian, who happened to have a law degree, to fill in. The librarian, Edwin Woodruff, accepted on condition that Jordan come to the first class to explain the unusual circumstances. “But Dr. Jordan did not appear,” Woodruff recounted, “so I made a frank explanation of the situation to the members of the class and stated that we would study law together. Thus the work started …”

With this accidental initiation, Woodruff discovered a love and talent for law teaching that led to a 33-year career at Stanford and Cornell (where he would become Dean). “The best law teacher I ever knew,” Abbott would later say of Woodruff.

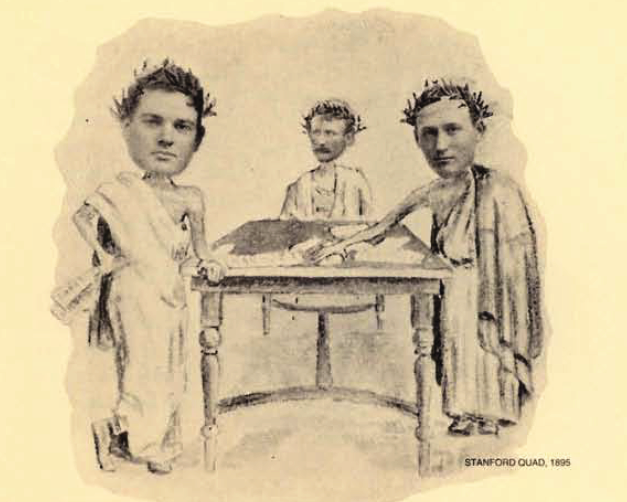

STUDENT REFORMERS.

Crusading students of the new Law Department made a dramatic impact on the larger University. Pledging to reorganize the haphazard student government of the two-year-old University, law student Ed “Sosh” Zion was elected student body president in September 1893. The competition for votes the following spring between Zion’s reformers and the insiders was so intense that Jordan complained of “presiding over a young Tammany Hall.” The reformers won a decisive victory in April 24, 1894, with the election of engineering student Herbert Hoover as treasurer and law students Lester Hinsdale and Herbert Hicks as student body president and football manager, respectively.

This montage from the university student yearbook pays tribute to the leaders (Hoover is on the left, Zion in the center) who had made a republic of student government.

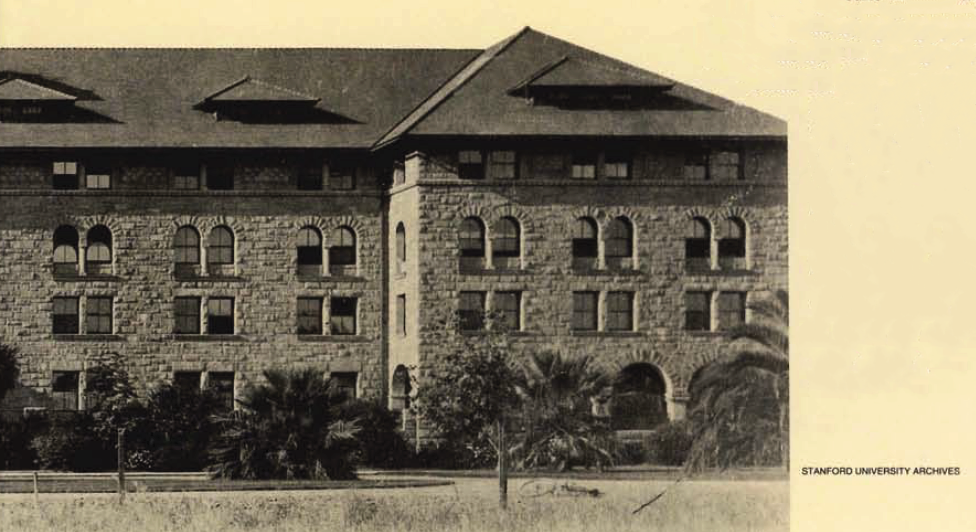

FROM THE GROUND UP.

Abbott’s early fears were almost realized, as the University approached bankruptcy following Stanford’s death. Nonetheless, Abbott did arrive in September 1894, the Department’s second year. He installed the Department’s first office and library in a bedroom in the men’s dormitory, Encina Hall (shown here in an 1895 photograph). He even built much of the furniture himself. To instruct the wide variety of students taking law classes, he evolved a teaching method that “happily combines the lecture, textbook and judicial decision,” as one student wrote. “A summary of each subject studied is dictated in the form of notes, and this is supplemented by the informal discussion and ‘quiz.’ ” With the University’s financial woes leading to the early departure of Harrison and Woodruff, Abbott was forced to do most of the teaching himself. “I have tried to saw wood with a dull saw,” Abbott complained to Jordan, “but I have ‘sawed,’ although my back has ached sometimes.” His labor was rewarded with rapid growth of the Department-by 1897, the second largest on campus.

OPEN DOORS.

As a primarily undergraduate division of a new university founded on egalitarian principles, the Law Department registered many students who might not have been welcome at more traditional law schools. Hispanic, Chinese, Japanese, and women students were enrolled in the Department’s first classes. Walter Fong, in 1896 the first Chinese graduate of Stanford, minored in law and became a member of a San Francisco law firm and later president of a college in Hong Kong.

STUDENT LIFE.

For its first decade, the Law Department reflected its largely undergraduate composition. The most celebrated law students were those who excelled on the football field, such as Jackson Reynolds and Charles Fickert (later among the Department’s most prominent alumni). Student life was dominated by a proliferation of law clubs, which combined moot court training with social camaraderie. The original members of the Arcade club posed for this turn-of-the-century photograph.

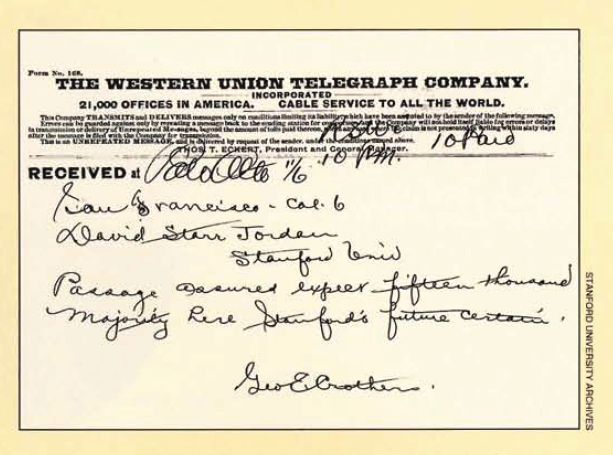

MAKING STANFORD LEGAL.

A different sort of club-this one formed by law alumni-probably saved Stanford University. In founding the institution, Leland Stanford had made use of unprecedented legal procedures that gave him absolute control. George Crothers, shortly after receiving the first M.A. issued by the Law Department in 1896, discovered that the University’s novel organization violated California law. With the help of some fellow law alumni, Crothers formed the Stanford University Constitutional Amendment Club to push for an amendment to the state constitution that would permit Stanford’s unique status. On November 6, 1900, after a year of intense campaigning, the amendment passed. Decades later, law professor George Osborne would call Crothers “the architect and builder, the refounder of Stanford’s present secure legal foundation and structure.”

TURNING PROFESSIONAL.

As the Law Department grew, it began to focus more on professional than on undergraduate education. Several new professors were added, including Clarke Whittier, who would teach at Stanford from 1897 to 1902 and (after a stint at Chicago) from 1915 to 1937. A comprehensive three-year program was implemented that would form the heart of the curriculum for decades. “We felt quite grown up,” recalled Whittier. And in May 1901, the Department awarded its first professional degree, an LL.B., to top student James Burcham.

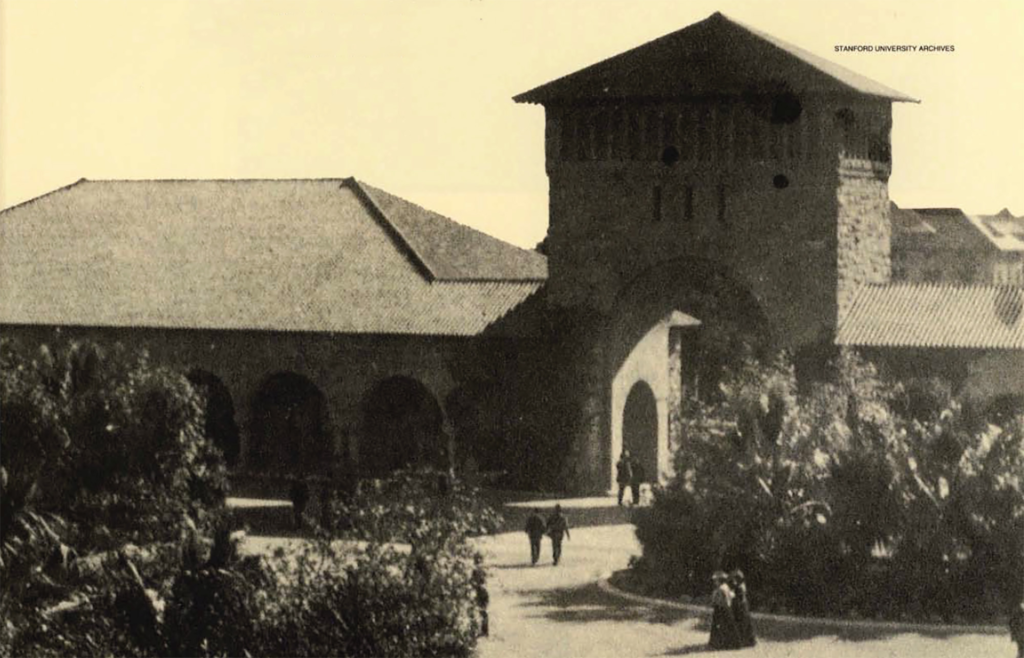

HOME ON THE QUAD.

In 1900, the Department moved from Encina Hall to the northeast side of the Inner Quadrangle (on the left side of this early photograph). The new quarters, which Law would occupy until 1950, contained two large recitation rooms, three faculty offices, and a library. Whittier’s comment: “We were too proud for words.”

PIONEERING WOMEN.

One distinguished graduate of the Department was Di Margaret Gardner, who became a Deputy City Prosecutor in Los Angeles. The Law faculty had mixed views about women students. Professor Abbott told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1901: “I do not believe much in the modern system of educating women….The tendency is to spoil a good woman to make a poor man out of her.” But Professor Whittier was more enlightened: “The few young women who joined our ranks were not in any separate category from the men,” he would recall. “There seems to be no sustainable objection to the admission of women to law schools.”

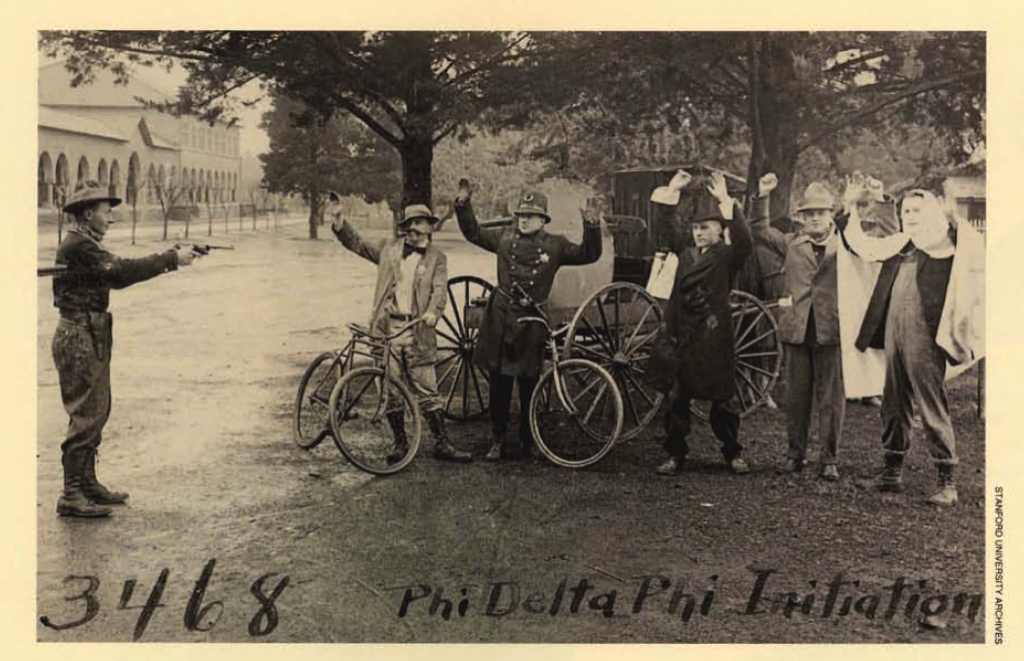

LAW FRATS.

Three law fraternities were begun in the early days. Dean Marion Rice Kirkwood would later write that the law fraternities “have regular meetings at which they give over a large part of their time to consideration of some legal matter, the argument of a moot case, the discussion of some proposed law reform, or the presentation of various points of view in practice by lawyers who have made a success in the profession. In these and other ways they develop in their members an interest in law as a science.” They also found time for fun, as shown in this photo of Phi Delta Phi, founded in 1897.

SHOCK AND AFTERSHOCK.

On August 18, 1906, philosopher and psychologist William James was staying at Professor Abbott’s home in Palo Alto (center in the early 20th-century photo above) when the great earthquake struck. James, eager to record his perceptions of the event, refused to budge, saying, “I’ve been waiting for this opportunity for years.” The Law Department headquarters on the Quad emerged relatively unscathed, but the living quarters of some members of the Department were damaged. Law student William Barkley was sleeping when “the chimney fell within 2 or 3 feet of my head. I tried to jump over the side of the railing, but the bricks were coming too thick and I was afraid the front porch would fall and mash me.” The Department suffered a greater jolt one month later, when Abbott announced that he was leaving to become a professor at Columbia Law School.

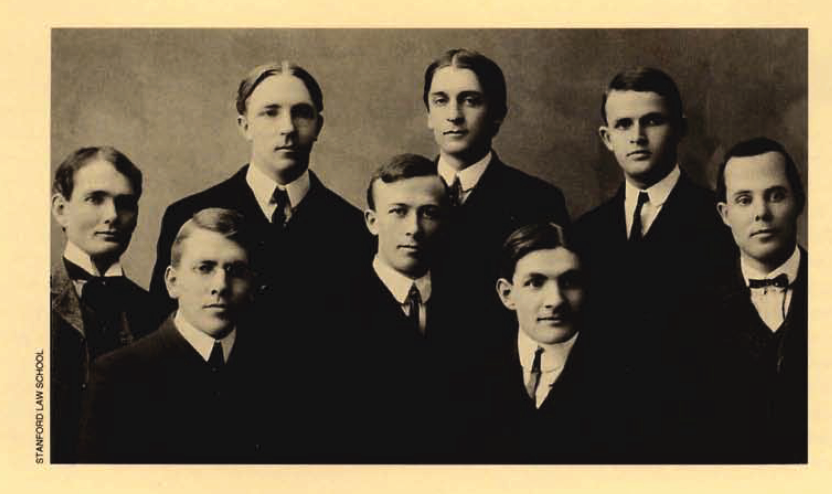

FROM DEPARTMENT TO SCHOOL.

Abbott’s tenure spanned just about the entire life of the Stanford Law Department. The face of the future can be seen in this photo of the faculty, taken in the spring of 1907 shortly after Abbott’s departure. Charles Huberich (center front) succeeded Abbott as executive head. Reflecting a national trend toward higher and more specialized standards for legal education, Huberich called for creation of “a true professional school.” By December 1908, President Jordan and the Stanford Trustees agreed and voted to change the Department into a Law School. A new addition to the faculty, Frederic Woodward, became the School’s first Dean; Charles Huston (upper left) would succeed him in the deanship in 1916. Arthur Cathcart (upper middle) taught at the Law School until 1938. Leon Lewis and George Boke (front left and right) were here only briefly. But Wesley Hohfeld (upper right) would become the early School’s most eminent scholar and a progenitor of the legal realist movement. Stanford was becoming a leading law school.

Howard Bromberg is currently working on a history of Stanford Law School. He holds a J.S.M. in addition to a J.D. degree, and was a teaching fellow from 1988 to 1990.