Three Strikes Project: Beyond Individual Client Representation

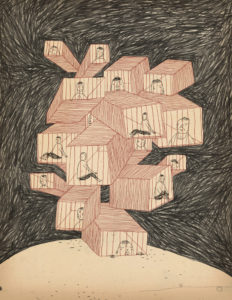

The United States excels in many areas. But one unwelcome bragging right is its incarceration rate: the highest per capita in the world. California is particularly bad in this respect. Adding to prison overcrowding—and to the state’s budget woes—is lifetime sentencing mandated by California’s “three strikes” law, widely regarded as the toughest in the country. The law has resulted in an estimated 4,000 prisoners serving lifetime sentences for nonviolent third strikes.

As California grapples with its budget and prison challenges, students enrolled in Stanford Law School’s Three Strikes Project have been chipping away at the issue since 2009 by representing incarcerated clients. To date, some 25 individuals sentenced to life in prison for nonviolent third strikes have been resentenced with their help. And last year, students enrolled in the project dove into something new. Representing the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF), they are helping to revise the law through a November ballot initiative so that nonviolent offenders can avoid lifetime sentences in the first place.

“We don’t dispute that our clients have committed crimes and deserve some punishment. Our argument is that sentencing for these nonviolent crimes under three strikes is excessive and in fact unconstitutional,” says Michael Romano, JD ’03, co-founder and director of the Three Strikes Project. “They should not be getting a 25-years-to-life sentence for buying a stolen cell phone or stealing a purse.”

THE FACES BEHIND THREE STRIKES

Malaina Freedman, JD ’12, is representing Larry, whose third strike was possession of stolen property. Larry’s two priors were for nonviolent burglaries. He was working hard to stay out of prison and holding down two jobs, when he bought a cell phone for his son—but it turned out to be stolen. Larry was sentenced to life under three strikes. Fifteen years have passed since he went to jail. His son is now a grown man, and Larry isn’t even close to a release date.

Freedman and her project partner got to know Larry well during their many prison visits with him. They also made an effort to get to know a few of the prison guards and, after some gentle persuasion and persistence, eventually secured declarations from two supporting Larry’s release. “You couldn’t get better declarations. They said that he’d saved the life of one guard and helped to relieve racial tension in prison,” says Freedman. A year on—after a lot of research, interviewing, and drafting—the project team is ready to file a habeas petition requesting resentencing for Larry. Then, it’s up to the judge.

“What the students are saying in these petitions is pretty extraordinary—that legal representation was subpar. It’s a big deal for a judge to consider this kind of claim and these cases aren’t overturned lightly,” says Romano.

But there is a small window of sentencing discretion that Romano believes their clients fit through: All have nonviolent third strikes and all have non-serious priors, and most have histories reaching back to childhood of neglect, abuse, drug and alcohol addiction, and mental health issues. That their attorneys didn’t raise these issues at trial is very hard to reconcile, says Romano.

The project is a structured learning experience with plenty of supervision and direction provided to the students as they represent their clients. But the students often learn more by studying the failures of the legal system.

“My client is actually clinically diagnosed as intellectually disabled,” says Emily Murphy, JD ’12, who participated in the project last spring and has been working on the initiative and trying to resolve her client’s case before she graduates. “This is especially challenging because he doesn’t know that about himself and wouldn’t self-identify in that way. But we dug up his history and had him evaluated and this is the diagnosis. And while his lawyer in the original trial ordered a psychiatric evaluation, records show he never followed through.” Murphy says she had an inkling about her client’s mental status as soon as she received his school records, which took all of one phone call to get.

“Both Emily’s client and Malaina’s client had trained lawyers and they wound up in prison with life sentences for some- thing quite minor,” says Romano. “Our students study the inadequacy of representation by reading the trial transcripts and going back and speaking to our clients, reading the Constitution and what it says about adequate representation, and then going in and providing it.”

AMENDING A LAW: THE BALLOT INITIATIVE

There are boxes of letters in the project’s office, each containing desperate pleas from prisoners and their families. As many as 10 letters are received each day, more than 5,000 total since 2009, according to Susan Champion, JD ’11, who participated in the project in 2010 and is now its research fellow. The project is the only legal organization in the country devoted to representing individuals serving life sentences for nonviolent crimes under California’s three strikes law, and word has spread in the prison system that this is the place to turn to for help.

The process of deciding on new clients is, Romano says, heartbreaking. “When you’re looking at these letters, you think what’s worse: A minor theft? Possession of a minimal amount of a drug?”

Policy work is an important component of experiential learning and the LDF ballot initiative, which will go to California voters in November, offers students a way for their work to impact far more nonviolent third strike prisoners than the project could ever represent individually. It also provides them with an ideal opportunity to both delve into research relevant to the three strikes law and to work with LDF, one of the premier civil rights organizations in the country.

The primary aim of the LDF initiative is to amend the law so that a life sentence is imposed only for serious or violent third strikes. “You get rid of individualized sentencing at serious cost to people, sending them to jail for 25 to life,” says David Mills, senior lecturer in law and professor of the practice of law at Stanford, who is also co-chair of the board of directors of LDF and instrumental in bringing this work to the project. “If you’re going to have three strikes, it should at least require that the third strike be serious. We’re the only state in the country that allows someone to go away for life for stealing a loaf of bread or possessing a tenth of a gram of cocaine. It’s one of the worst laws.”

LDF relied on Romano and his team of students to figure out the details of the proposed initiative and to make sure it was correct—that all the right penal codes and sections were on the ballot initiative. Research done by Hannah Shearer, JD ’12, was compiled in a massive spreadsheet with more than 650 crimes and detailed analyses on how each crime would be affected by the change in the three strikes law as proposed by the initiative.

“One of the things we all learned is that writing a statute is incredibly complicated. Hannah had to say ‘here is the penal code, and here are all of the crimes, and this is how we ranked them.’ She came up with hundreds of scenarios,” says Romano. “And when it came to the actual drafting part of it, which the students also did, Malaina was one of the last people to have their hands on the document—to read it and make sure it said what we meant it to say.”

While working on the initiative students also learned about the financial cost of the three strikes law. The Legislative Analyst’s Office fiscal impact report estimates a long-term savings of $100 million a year if this initiative is approved and nonviolent prisoners are kept out of prison for such long periods. “I believe that between the financial savings and the human suffering savings this is an extraordinarily important moment, a watershed moment for criminal justice,” says Mills.

CAREER PREPARATION

The project offers students an opportunity to develop practical expertise they’ll need as lawyers, while emphasizing the importance of legal services. “When we started working with the project, we knew nothing,” says Shearer. “And very quickly we were going to courthouses and going to prison, doing research and writing briefs. It was incredible preparation.” Shearer will be joining Munger, Tolles, & Olson LLP in Los Angeles as an associate next year, a firm she chose, she says, specifically because it strongly supports pro bono work.

While most of his students won’t be public defenders, Romano wants them to remember how important their skills are. “Ultimately what I hope to teach is that they can go to court and make a real difference. They can work on policy and bring about change. We need to reinforce the entrepreneurial and ethical spirit in law students—that one lawyer can make a big difference. I hope that they derive inspiration to take on challenges and seemingly lost causes no matter where they eventually go to work.” SL

Check out the Three Strikes Project website, Facebook page, or learn more about the initiative.