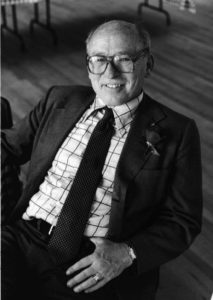

Tom Elke

On Sunday, June 3, 2012, Tom Elke, LLB ’52 (BS ’49), one of the founders of Elke Farella & Braun and my dear friend, passed away.

Tom, Jerry Braun, LLB ’53 (BA ’51), and I met at Stanford Law School in 1951—and despite our wildly disparate geographic origins and life experiences, we became fast friends. In those rare moments away from our arduous study regimes, we joked about one day starting our own firm. Twelve years later, on February 1, 1962, Elke Farella & Braun came to pass.

“The Elk”—as we affectionately called him—was the centerpiece of our trio and without him the firm would have remained a youthful fiction. Last February, at the celebration of the firm’s 50th anniversary (now known as Farella Braun + Martel LLP), Tom made an appearance, giving our younger lawyers and staff a brief glimpse of this extraordinary man and a taste of his humor. He delivered one of his classic injunctions to the group saying, “Seek excellence, but don’t take yourselves too seriously.” Tom left the firm about seven years after we started because, in his words, we were “getting organized.” He abhorred organization and discipline. Despite his departure, Tom, Jerry, John Martel, and I remained close friends, and while out on his own Tom engaged the firm with respect to some large and intriguing cases.

Tom’s brilliance is reflected in the following, highly condensed version of his life’s journey. He had an IQ of meteoric proportions. In high school, he recorded the highest score ever in the Pepsi-Cola National Scholarship Competition and earned access to Stanford as a freshman shortly after his 16th birthday. He had a near photographic memory; he was a speed-reader and a walking encyclopedia in history, astronomy, religion, physics, math, and philosophy. He received his undergraduate degree at Stanford when he was 19. While in my third year of law school, I worked as a bartender for a professorial reception. The head of the physics department at Stanford, for whom I was mixing a drink, asked what my field of study was. When I said “law,” he brought up Tom’s name and said he was one of the few people he had ever known who understood Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Tom’s complexity is reflected in the fact that despite his towering intellectual achievements at Stanford, he competed for and won the right to be Stanford’s head cheerleader. His enthusiasm was boundless, as were his curiosity and range. In the second year of the firm’s existence, he enrolled full time in the San Francisco Theological Seminary and without stinting on his lawyer duties in the firm, he became valedictorian of his class, and then a pastor in Oakland. At the time of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, he went to Selma, Alabama, and did support work for and joined the civil rights marchers to Montgomery. In his professional life, Tom was most proud of the time and money he dedicated to establishing a public interest law curriculum at Stanford Law School with Stanford’s first professor of public interest law.

For decades Tom fought various illnesses successfully, and it was only a few weeks before he died that it became evident that this time would be the final chapter of his life. I had a joyful visit with him a few days before he passed away in his sleep. I will be eternally grateful that he was in my life.