Tom Heller A Nobel Effort for the Environment

When the Nobel committee announced last October that it was awarding the prize for peace both to former U.S. Vice President Al Gore and to the network of experts who make up the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Thomas C. Heller was taken completely by surprise. •

“The combination of science and morality the committee’s decision reflected was a lovely recognition of the complex dimensions of getting at this problem,” says Heller, the Lewis Talbot and Nadine Hearn Shelton Professor of International Legal Studies, who, as one of several Stanford faculty representatives on the IPCC, joined Gore at his press conference in Palo Alto when the award was acknowledged.

Equally remarkable to those who know Heller was that he was in town to share the spotlight. While climatologists, biologists, astrophysicists, and others from the IPCC try to identify and track the impacts and timelines of a warming planet, Heller works the complex economic policy side of the equation. For more than 15 years he has traveled the globe for face-to-face negotiations with government representatives, cajoling countries to take concrete steps to mitigate the impacts of climate change. That’s a people-to-people exercise in negotiating, dealmaking, and understanding. Heller’s commitment to this issue of global climate change means that he must travel extensively on behalf of the IPCC and the United Nations Secretary General, focusing special attention on trying to figure out ways to channel the desires and demands of entire nations into a path that reduces carbon emissions.

It wasn’t always clear that Heller would focus on climate change, though his eclectic background in global economic development, international tax law, and a stint as director of the Stanford Overseas Studies Program in the 1980s have served him well. He says he “fell into climate change” when, in advance of the now famous Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, a Swiss business associate asked him to put his experience in development to work to help reduce tension and antagonism between business people and government regulators headed for Rio. “I started to work on this without any sense of the importance it would have,” he says. That summit resulted in a series of steps, including the Kyoto Protocol, that Heller and others are still trying to advance today.

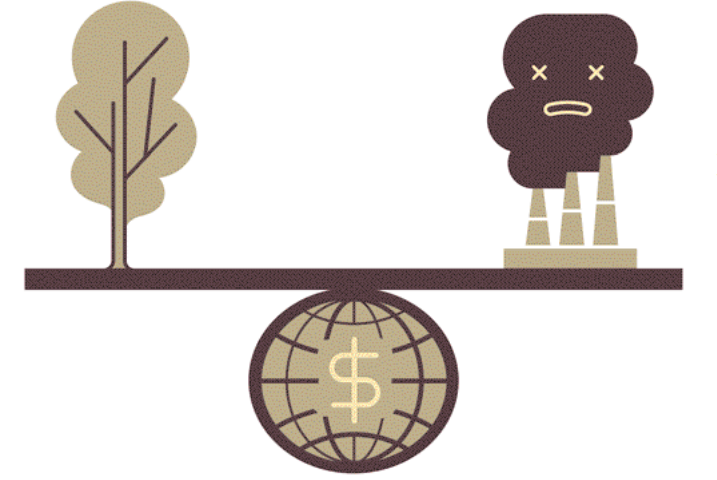

Heller doesn’t believe that answers lie in imposing regulations on developing countries. “Climate is a derivative problem that results from energy use, transportation, and land use issues. These three industries are at the heart of economic development.” Heller’s approach, instead, focuses on the realities of economic growth. “We need to look at what people are trying to do with growth and see if we can get them to do it in a way that is less damaging to the environment,” he says.

Heller sees China as a prime example. “This country is probably the single most tractable place on the planet where one can get at climate change,” he says. Although China’s environmental concerns have been secondary to its desire for economic growth—because it is still developing and, in particular, building new energy plants—Heller sees opportunity.

“There are steps you can take that would reduce sulfur and carbon and others that would just reduce sulfur. You can have a huge impact when you build new systems. It strikes me that one can focus on goals that they’re already expressing and move to climate reform,” he says. In that vein, Heller is working with the Chinese to pursue solutions such as natural gas-fired power plants that would dramatically lower carbon emissions and improve local air quality.

“Tom has worked hard to build relationships with thinkers in India and China and around the world and his approach is nuanced,” observes Michael Wara ’06, a research fellow at the law school who works with Heller. Heller expects the rapidly growing emissions in China and India to occupy the bulk of his attention in the next two years. “We’re trying to figure out what steps they’ll take and what financial and economic support they will need,” he says.

“Tom has a very good understanding of political economy and how things work in practice,” says Bert Metz, the Dutch co-chair of the IPCC’s Working Group III, which focuses on mitigation strategies and of which Heller is a member. In recent years, for example, Heller has been the first to acknowledge that a market-based framework to lower emissions through so-called carbon trading credits, which was developed as part of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, has stalled out. The idea was to encourage developing nations to invest in clean technology and then sell related “carbon credits” to countries who agreed to cap their emissions. However, he and others now say that the complex systems have been manipulated widely to generate sales without meaningful reductions in emissions. Heller wants to put the breaks on expanding ideas like this one that are “symbolically attractive” but not environmentally effective.

Heller is optimistic about recent initiatives such as the climate change conference in Bali last December, which set out a roadmap for further negotiations designed to conclude in 2009. He says that for the first time leading developing countries recognize that they will have to constrain emissions after they peak in 2020. He also thinks that, with a change in administration imminent, the United States is poised to be a more active force. “If the U.S. doesn’t act,” he warns, “the framework will collapse.”

In addition to his efforts on behalf of climate change broadly, Heller is a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and he also runs the Rule of Law Program for the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law. He is the first to admit the current pace of his schedule is grueling and that he can’t sustain the intensity of his efforts indefinitely. But he says he is determined to capitalize on the public attention that Gore and the Nobel Peace Prize have brought to the issues of climate change.

“He’s in a position to make a real difference and I think he feels that sense of mission,” says Wara.