We Are Just Getting Started

With pioneer nerve and clarity of purpose, Kathleen Sullivan began her deanship at full speed and hasn’t slowed since.

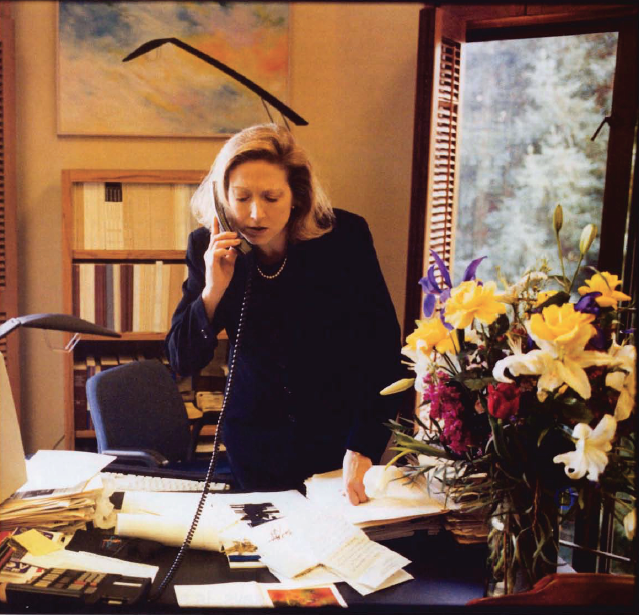

KATHLEEN SULLIVAN’S OFFICE chair is getting one heck of a workout. As she considers a question, the chair’s occupant swivels 180 degrees and back, her fingers fashioned into a steeple, head slightly askew. She scans the landscape like a sentry on duty, antenna deployed. When the chair stops moving, listen up.

“I want Stanford Law School to be the place where law faculty most want to teach and the place where law students most want to study,” she says finally, leaning forward for punctuation. And the chair begins to dance again.

Kathleen Sullivan is all about movement. Installed as dean of Stanford Law School on September 1, 12 days after her 44th birthday, Sullivan has blasted through the first few treacherous, twisty miles with hardly a skid mark. The first woman to lead the Law School-or any of Stanford’s seven schools-has embraced her pioneer status with a pioneer spirit, and demonstrated a restless intensity. She has big plans, and like the moderate earthquake that shuddered through the Bay Area just before she took office, she’s ready to rumble.

“We’re poised right now to become the most exciting place in the country for legal education,” Sullivan said. “We have only just begun to realize the true potential of Stanford Law School. This is no time to sit back and rest on what we’ve accomplished.”

Anybody who thought Sullivan would enter her deanship timidly doesn’t know her very well. “Unlike some other people I’ve seen on the verge of a deanship, filled mostly with trepidation, self-doubt, and anxiety, she does not seem to be plagued by any of that,” said mentor and friend Laurence Tribe, professor at Harvard Law School. “Kathleen is not a person who toots her own horn or who has an exaggerated sense of what she can accomplish; she has a great deal of humility where it is appropriate. But she has a real sense of mission.”

Central to that mission, according to Sullivan, is seeing to it that Stanford produces lawyers who love the law. “Part of our job, beginning on the first day of their first year of law school, is to make students feel they are part of a noble profession; that when they come in they’re learning how to speak a new language and think in new ways,” she said.

She is unabashedly proud of the law and of being a lawyer. You won’t find her apologizing for the profession or shrinking from a scornful public conditioned to think of all lawyers as predators. “Lawyers do heroic work,” she told 1L students in an expansive and impassioned address during orientation week. She lauded lawyers as public servants, essential producers of agreements without which society would collapse. “If we didn’t have lawyers,” she said, “we’d have to invent them.”

Her lack of ambivalence sends an important message to students, says Pam Karlan, professor of law and academic associate dean. “If you can convey to students that being a lawyer is a great thing, then you can get them to stop focusing on the idea that they are going to leave law school and make lots of money but be miserable the entire time they’re doing it,” she said.

Sullivan’s philosophical position also can serve as an antidote to the dreary acclamations heard from outside the Law School about the profession, says Tribe. “In the many instances when professors, and sometimes deans, have a barely concealed contempt or at least a readily discernible disinterest in the practice of law, there is a very serious disconnect between the professor and/or the dean and the mission of the institution,” he said. “Students are smart enough to detect when the person who is teaching them couldn’t imagine spending a satisfying life doing what it is that they are going to do.”

In short, Sullivan has the capacity to move people, to shape agendas. “When I think of the people who have influenced my career, Kathleen is right at the top of the list,” said Julie Lythcott-Haims, associate dean for student affairs at SLS and a former student of Sullivan’s at Harvard. “She makes you want to be better than you are, to stretch beyond your potential. Having a person like that leading the Law School transforms the experience from one of drudgery into one that is incredibly rewarding. She makes you feel like it matters.”

Sullivan always has had an eye out for underdogs. She is the product of an Irish Catholic family, which for generations helped supply New York City with police officers and priests. From a very early age, she demonstrated giftedness and a willingness to challenge convention. She was such a good reader in kindergarten that teachers passed her straight to the second grade. In catechism class at age 8, she inferred that if the Father was a “He” and the Son was a “He,” the Holy Ghost must be a “She,” and said as much, drawing a reprimand. It wasn’t the last time gender became an issue between her and the Church. Later that year Sullivan learned that women were excluded from the priesthood, a disappointment insofar as she thought she might want to join it. “That’s one reason I became a lawyer,” she said.

Sullivan’s talent and ambition were matched by a willingness to outwork everybody around her, perhaps payment for the sacrifices her parents, grandparents, and others made on her behalf, she says. “The people in the family who came before me made it possible for me to have opportunities. They were the ones who crossed the ocean. I don’t give myself that much credit,” she said.

She thought literature might be her calling, but discovered the law as an undergraduate at Cornell, moved by her admiration for lawyers who repaired the country following the Watergate scandal. She spent two years as a Marshall Scholar at Oxford studying philosophy, politics, and economics, then headed to Harvard Law School.

Although she distinguished herself academically, graduating with honors and helping her team win the moot court competition, Sullivan was not fanatical about her studies. She maintained balance, combining an abundant social life with a scholarly mindset, says friend and moot court partner Eric Havian, an attorney at Phillips & Cohen in San Francisco. “Her focus was not particularly narrow, which is not typical of law students. She was curious about many different areas of life,” Havian said. “She was a tremendously engaging, vibrant person to be around.”

And her court skills weren’t confined to rooms with paneled walls. “When we played tennis I seemed to always spend a lot of time running down balls,” Havian said. “She had a downright vicious forehand.”

She flourished under the guidance of Tribe, with whom she collaborated on a Supreme Court brief as a 3L, and of Professor Susan Estrich, whose “ferocious brilliance” was a source of inspiration, says Sullivan. She emerged from law school hungry for the courtroom.

After a year clerking for Judge James L. Oakes of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and two years of litigation work in Boston, Sullivan began to receive offers from leading law schools in the East, and was hired by Harvard in 1984. In 1992, the year in which she won Harvard’s top teaching award, Sullivan spent the spring semester as a visiting professor at Stanford Law School. Teri Little ’94, an attorney at Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati in Palo Alto and a former research assistant for Sullivan, recalls the buzz among students created by Sullivan’s visit. “We knew she was this famous lawyer, and we were excited to have her there, but I don’t think we realized just how amazing she was,” Little said. “She’s the Michael Jordan of the legal world.”

Near the end of the semester, “in a panic” that Sullivan was about to leave and never return, Little, a 1L at the time, organized a grassroots effort to pluck Sullivan from Harvard. Law students petitioned Stanford President Gerhard Casper and Dean Paul Brest to pursue Sullivan despite a University-wide cap on faculty hiring. “We worked on her, too,” Little said. One particular episode has passed into legend. During one of her final class sessions, Sullivan was writing furiously on a chalkboard, ran out of space, and pulled down anotl1er board to resume. But before she commenced writing, she was stunned into silence by what already had been written there by her students, predicting this moment. Scrawled on the board were the words “Defect to Stanford.”

One year later, she did just that.

Sullivan brings to the deanship a cache of media and courtroom experience that may be useful in her role as the Law School’s leading advocate. Acknowledged as a superb scholar and teacher, Sullivan is perhaps first and foremost a great lawyer. Her reputation was established by her performances as a litigator in a handful of Supreme Court cases, on her own and in collaboration with Tribe. She won some and lost some, but always impressed with her rhetorical skills and what one writer called “a Zen-like ability to make the complex clear.” Many of those cases involved civil rights issues, about which Sullivan is particularly passionate. “What drives me is the conviction that the courts are the only place where people who are politically powerless can get a fair shake,” she once told a reporter. “You can never underestimate how important it is to have lawyers and courts to defend people whom lots of people don’t like.”

She is accustomed to participating in public debate. Her articles have appeared in The New York Times, Washington Post, New York Times Review of Books, and New Republic, among other publications. She has provided commentary on a range of issues about the law on programs like Nightline and The Newshour with Jim Lehrer and once sparred with former Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork on CNN’s Crossfire.

“I don’t think that a great law school can have a dean whose only special strengths are administrative and diplomatic,” said Tribe. “The dean is, among other things, an ambassador for the school. It’s not nearly as easy for somebody who is purely a theoretician and who really doesn’t have a clue about law practice at the highest levels to be as effective a spokesperson for the school.”

Karlan says Sullivan’s advocacy skills not only will help the Law School, they will help the profession. “The same thing she can convey to students she can convey to the public, which is that being a lawyer is a great thing and training lawyers is a great thing. She speaks in a language that smart people who aren’t lawyers can understand,” she said.

At a speech to the Commonwealth Club of California late last summer, Sullivan offered a counterpoint to an earlier address to the group by former Vice President Dan Quayle, who characterized the legal profession as bloated, greedy, and motivated by self-interest. “A lot of what lawyers do is help people avoid conflicts,” she said. “They playa huge role in the normative ordering of society that has no clear substitute. It can’t be done by organized religion by itself, it can’t be done by social custom by itself, it can’t be done by markets by themselves. … If you could suddenly eliminate the lawyers from the world in one fell swoop, there would be a lot of conflict and calamity that would come to pass and somebody would have to pick up the pieces. It’s that invisible preventive and preemptive role that is worth thinking about quite carefully.”

Whether Sullivan can maintain a pace to accommodate regular decanal duties and Nightline appearances remains to be seen. She acknowledges that the job has many demands, but she hopes “to do it all.” She is teaching constitutional law to first-year students next spring and hopes to continue teaching at least one course each year throughout her tenure as dean.

Although Sullivan figures to be an effective advocate for the Law School with outside audiences, she emphasizes that her primary focus will be internal, being attentive to institutional needs. Faculty believe that, too. “I think she has a sense of priorities that her role is to facilitate the main mission of the Law School, which is teaching and research. That’s what I think she’ll focus on,” said A. Mitchell Polinsky, Josephine Scott Crocker Professor of Law and Economics.

In the weeks before and after she took over as dean, Sullivan traveled extensively, meeting alumni and broadening her understanding of their role in Law School affairs. Her personal skills, intellectual agility, and abundant energy often were on display, says Martin Shell, associate dean for external relations. He recalls that Sullivan once wrote an opinion article for the New York Times “in the middle of the night” and followed that with a 14-hour day of travel and meetings, while still delivering the piece for the next day’s paper. “Of course, the article read like somebody had spent weeks perfecting it,” Shell said. “We’re going to learn a lot from her.”

Sullivan sets high standards for herself and others, say colleagues, but also is approachable and empathetic. Her intellectual prowess-former student Jay Wexler ’97 once called her “scary smart”––might be intimidating if not for her affable charm and warm sense of humor. “One reason she isn’t intimidating––aside from the fact that she’s incredibly charming––is that she can deal with people on the basis of their ideas,” said Karlan. “She’s not trying to occupy the whole field and make everything about her idea.”

Moreover, she’s just plain fun to be around, says Tribe, who can reconstruct elegant, perfectly delivered jokes he heard for the first time from Sullivan. “I don’t know whether she made them up, but I had never heard them before,” he said. She has even been known to crack jokes during Supreme Court arguments.

Sullivan has demonstrated that same humanity in her classroom. Little says Sullivan the teacher empowers students with a sense of worthiness that is critical to their success. “When you are a student at a top-tier law school, you’re surrounded by very bright people, and you’re insecure,” said Little. “Kathleen has this wonderful way of making you feel significant and intelligent. She has such generosity.”

Lythcott-Haims recalls a meeting she had with Sullivan as a student at Harvard that decidedly changed her outlook. “I began the conversation with ‘I’m Julie, I’m not sure if you know who I am,’ et cetera, and Kathleen stopped me and said, ‘Of course I know who you are. In class I see your expressions change and know that you want to say something, and I wish you would.’

“I can’t tell you what it meant to me at that time to have somebody who was so smart and so well respected notice me in a crowd of two hundred fifty students. She really gave me my voice. That is the moment I began to enjoy law school.”

Particularly for women, Sullivan’s presence will help prepare students for work in a legal culture that has yet to assimilate women fully, says Little. “I can’t overemphasize the importance of having a woman like Kathleen as dean. She is a wonderful role model,” she said.

Sullivan’s remarks at the 1996 Commencement may serve as a talisman for students who will come to know her, and her values, as dean. “When you look back at your life from the other end, you will ask not just how many glittering ornaments adorn your resume, or how clever your arguments have been,” Sullivan told ’96 graduates. “You will ask if you were brave and bold and true and just. You will ask whether you sold your great skills and greater talents to the highest bidder, or shared them with some of those in greater need. You’ll ask whether you took responsibility for your actions, or blamed them on someone else’s snafu. You will ask whether you took a higher road than your enemies, and whether you treated those less powerful than you as you would be treated yourself. Only then will you know that good conscience is the only sure reward. Please try to remember that in the meantime.”