Why Looking After the Ocean is Not Just a Job for Islanders

(Originally published by World Economic Forum on October 27, 2022)

For some, climate change is a topic of study or something they’re interested in. However, for islanders like me, it’s not abstract or theoretical. It is the fate that determines whether we sink or swim – literally. As the Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley poignantly asked in her COP26 speech, “will they mourn us on the frontline?”

Living in Hawaiʻi and South Florida, I grew up in communities with inextricable and reciprocal relationships with nature, particularly the ocean. As a little boy, I was out hunting for crabs, exploring mangroves, chasing the flow of the tide at the beach. My childhood saw the growth of my profound fascination with nature but also exposed me to biodiversity collapses and the impact of climate change. I remember seeing people trucking in sand because of coastal erosion, and having to miss school because Hurricane Wilma wiped out all electricity for weeks.

People who live in places surrounded by water don’t have the luxury of debating whether the climate crisis is urgent or not. We’re seeing it every day, like the famous story of Florida residents who found an octopus in a parking garage, or more recently, the victims in Puerto Rico grappling with the pain and aftermath of Hurricane Fiona.

Those in landlocked countries may feel further removed from this sort of climate change impact. This was one of the key challenges I sought to address when I was selected as one of the two United States representatives for the Pre-COP26 UN Youth4Climate Summit in Milan. My counterpart, Ruth Łchavaya K’isen Miller, is an Indigenous community leader from Alaska, which is dealing with more coastal erosion and sea-level rise due to climate change, and most recently a devastating typhoon. As youth advocates, we were tasked with creating youth-driven solutions in our Youth4Climate Manifesto and effectively discussing climate change in an accessible way that would resonate with people that may not live in frontline communities.

Why we need the Ocean

As the UN Security Council has recognised, climate change is a threat multiplier, affecting every domain and every community. For international health, warming temperatures facilitate the proliferation of tropical and zoonotic diseases like Zika and Dengue Fever, and as we saw in Brazil, it particularly affects low income communities. For those in coastal communities, this impact is particularly visible because the climate affects the ocean, and the ocean is part of everyday life.

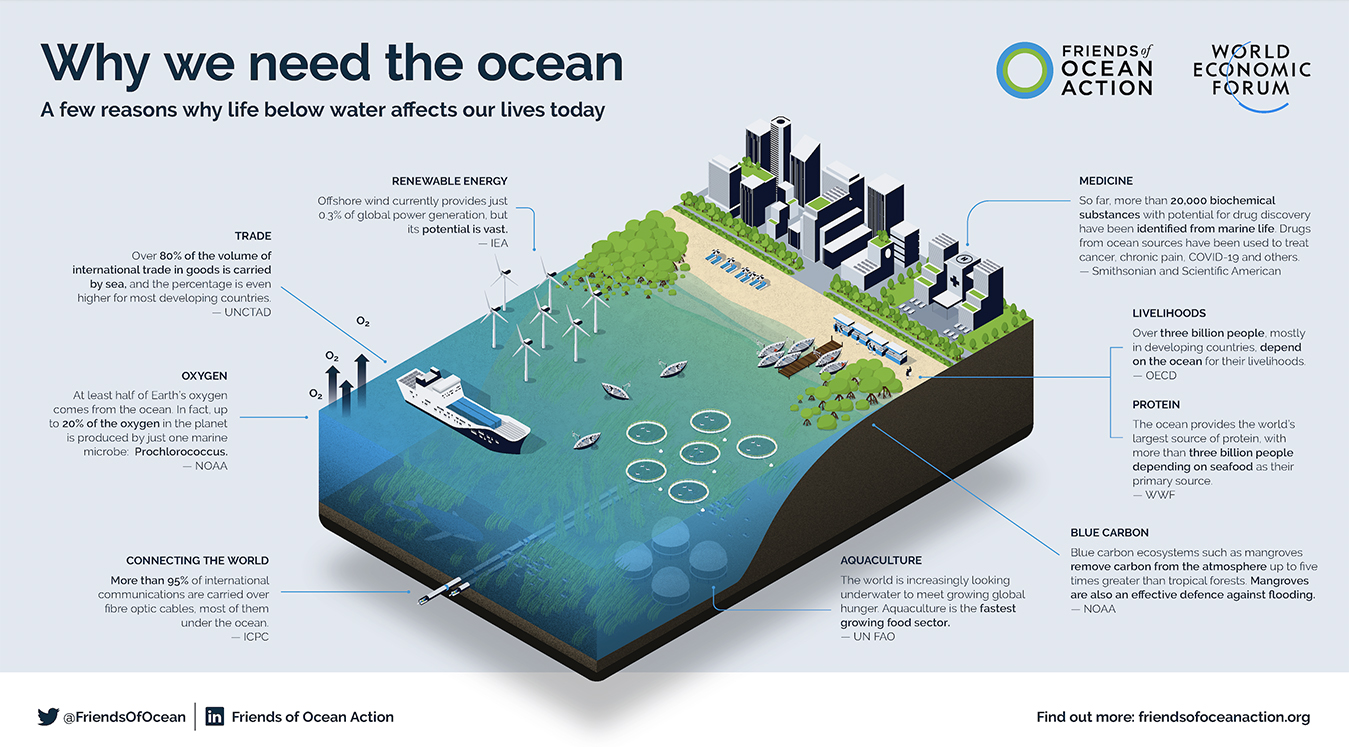

However, the ocean’s importance isn’t limited to these ocean communities. Everyone is part of an ocean community, whether they recognize yet it or not. The ocean is a key element of the water cycle and drives both the day-to-day weather and climate around the world. It is a major source of blue food, or food from aquatic sources, which is poised to revolutionize global food systems. For the United States, the marine economy contributed approximately $361 billion to GDP and employed around 2.2 million people. It provides half of the oxygen on Earth and is an unparalleled carbon sink, absorbing approximately 25% of anthropogenic carbon, with new research indicating the ocean carbon sink may be even 9-11% larger. It connects us all and spreads across 70% of the planet. The ocean is our greatest shared gift and it’s simply too big to ignore.

I will be attending the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27) again this year and I hope to hear more about the ocean. It should not be relegated to some siloed sessions at the conference. In my work in advocacy for ocean health and fighting climate change, I’ve met many people who are focused on the two topics but there often isn’t enough overlap. Many people still talk about the ocean as if it’s a niche issue specifically for islanders. The climate change impact on the ocean may be seen in frontline coastal communities first, but this impact flows around the world.

For developed countries like the U.S., these adverse effects are felt unequally across racial and socio-economic divides, with 59.2% of coastal city residents identifying as Black, Indigenous, and people of color. We see this reality in cases like the flooding in Pakistan, Fiji launching the world’s first relocation fund for climate displaced communities, and food insecurity for fishing communities around the world, with a heightened risk of exploitation of women and children after climate-induced disasters.

I have many hopes for COP27. In addition to seeing the ocean become more central to the debate, I also hope to see more progress regarding loss and damage, the recognition of the threats that global cultures face due to climate change and the empowerment of frontline communities through data and ocean modelling, artificial intelligence, and scalable entrepreneurship. As Ugandan youth activist Vanessa Nakate explains, “you can not adapt to lost culture and heritage.”

For emergent ocean science and technology, I also hope to see concerted efforts for ensuring local communities can harness and benefit from the immense potential of eDNA and marine genetic resources. Furthermore, there needs to be heightened respect for and investment in Indigenous science and biocultural resource management, without parachute science and underpinned by free prior and informed prior consent.

I hold on to hope because of the infectious energy and optimism of the youth and islander community, who are leading impactful climate action and expanding the climate change conversation. I always say, those of us who come from islands may come from small places but our pride is not small, and neither is our resilience. My friends from the Pacific Climate Warriors have a powerful saying that continues to motivate me: “We are not drowning, we are fighting. And like the ocean we are rising”.

Rising to the challenge of climate change is not a job that only belongs to islanders. We all have a stake in ensuring that our planet and our ocean is healthy. Therefore, COP27 must be the meeting place where we, as a global community, rise up together, keep each other accountable and get to work.