Reshaping 911 Response in the Bay Area

In 2023, what happens when you call 911 in San Francisco?

After a reform that once seemed radical, police are no longer the only, or even the main, first responders for many emergency calls. If a person appears to be having a mental health or drug-related crisis, there’s a good chance that the city’s new Street Crisis Response Team will be dispatched to the scene instead. New data released by the city shows that the team has now handled more than 15,000 calls since 2020, and, recently, San Francisco awarded a multi-million-dollar contract to a nonprofit to provide another alternative response to calls about homelessness. Still, recent headlines ask whether the Crisis Team itself might be “in crisis,” and critics wonder whether the selected nonprofit partner is up to the job.

San Francisco’s Crisis Response Team was developed in the wake of the 2020 protests in response to the police murder of George Floyd. In the following months, the conversation around community safety shifted dramatically across the country. After decades of research into different ways of incorporating mental health awareness into police training, some cities concluded that a completely police-free alternative emergency response model might be worth investing in and implementing. In the years since 2020, at least 19 of the top 50 police jurisdictions have piloted some version of their own alternative first responder. These programs involve unarmed, non-law enforcement responders—often mental health professionals and medical specialists—who attend to low-risk, nonviolent emergency calls. In a recent report, the Brennan Center for Justice cataloged the alternative police responder models that have been implemented by the largest U.S. law enforcement agencies during this time period.

Alternative first responders provide an evidence-based opportunity to attend to mental health, substance abuse, and homelessness—conditions that prompt as many as 21-38 percent of 911 calls to law enforcement. Yet alternative first responders cannot, on their own, halt police violence and the racially disparate treatment of people of color; instead, they only address a portion of the work that police perform. It is worth noting that during the same post-2020 “reform” period, many cities actually raised their police budgets—even in the face of calls for alternative approaches that would reduce the need for police intervention. These budget increases often were made to address perceived or actual increases in crime.

Still, rethinking the 911 call may offer a key point of intercept in disrupting the systems that too often criminalize the mentally ill, which is especially pertinent in a country where the largest mental health care providers are jails and not hospitals. These models also have the potential to decrease the disproportionate amount of contact that takes place between the police and young Black men, incidents that often have lifelong negative health implications and contribute to the racialized patterns of trauma that work against disadvantaged, marginalized communities.

In 2021, our Center released a report, “Safety Beyond Policing: Promoting Care Over Criminalization,” which recommended the implementation of mental health teams as an important first step in the movement for innovation in community safety. Now, three years out from the 2020 protests in April 2023, we have some early results from the pilot programs of alternative first responders. Some, like San Francisco’s Street Crisis Response Team, have rapidly ramped up the number of calls they receive and the geographic areas they serve. Others are still operating under set hours and with coverage limited to certain neighborhoods. We have also learned that there is great variation within and among approaches to non-police responders. Even though many of these teams were initially modeled on the CAHOOTs team—the first widely acclaimed non-police responder that was developed in 1989 in Eugene, Oregon—many cities have come to recognize that the unique issues of each city require tailored solutions. This is particularly evident in the Bay Area, where cities are pursuing a wide range of innovative non-police responders.

For example in San Francisco, in addition to the Street Crisis Response Team, the city is fielding companion teams that focus specifically on drug use and homeless outreach. San Francisco recently signed a contract with Urban Alchemy, a nonprofit that works with California cities to provide a civilian street response and to build on a community-based homelessness team that has been in the works for months. Still, critics contend that Urban Alchemy workers are not adequately prepared for the job, and that the program could be improved.

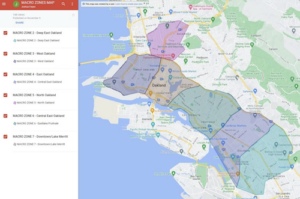

In Oakland, the City Council launched a response team, the Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland, which began a pilot trial in March 2022. Additionally, the Anti Police-Terror Project, an Oakland-based nonprofit, runs a community-based alternative response team called Mental Health First that is purposely de-affiliated from the historically police-focused 911 system—and the perceived and actual harms that it has caused to communities of color. This model was first piloted in MH First Sacramento, an early and innovative first responder initiative that was developed in California’s capital.

Santa Clara County, the largest county in Northern California, is working on developing behavioral health teams that will operate in San Jose and across the county. The San Jose Police Department is a relatively small department compared to other major American cities; in 2022, San Jose boasted the lowest homicide rate per capita among the 50 largest cities in the USA. Nonetheless, both the police department and the mobile crisis response teams have run into staffing issues that have undermined their performance. In the first few months of its operation, the new mental health helpline even triggered police-only responses, contrary to the mental health-focused approach that it was designed to provide. Karen Meagher, the clinical director of the mobile crisis team, cautioned about the need for patience: “We’re not going to flip a light switch and everything’s going to be different. But [the new mental health helpline is] grounded in the right perspective and the right philosophy.”

Meanwhile, Berkeley is gearing up to pilot a new Specialized Care Unit that will start responding to drug and mental health emergencies in June. Even though the program is short on funds and still working out logistics, Samantha Russell, the unit’s director, noted Berkeley’s “high hopes” for the initiative in a recent interview, explaining that the new approach will “give civilian responders more access to people in crisis than any other program in the Bay Area.”

Through our research, we are aiming to provide an anatomy of non-police alternative first response as it exists today, in 2023, in the Bay Area. We will ask: What obstacles arose to the development of these alternative first responders? Can these programs withstand long-term political scrutiny if they are getting heavily criticized? And what does success look like for these teams?

We are taking a closer look at San Francisco’s Street Crisis Response Team and other government-run community responder models that are being piloted in Oakland, Santa Clara County, and Berkeley. We are also considering the challenges that go into scaling these alternative first response programs from experimental pilots to established departments, as they operate in different stages of development in four jurisdictions across the Bay Area. As we consider these programs, it is worth acknowledging the unprecedented nature of the work that alternative first responders are attempting to achieve. After decades of trying to train police in Crisis Intervention Training or add mental health professionals to police teams, this is the first time local Bay Area governments have seriously funded completely police-free responders. In our research, we seek to explore the growing pains of these teams, the debates emerging around the models, and the potential vitality of the long-term vision.