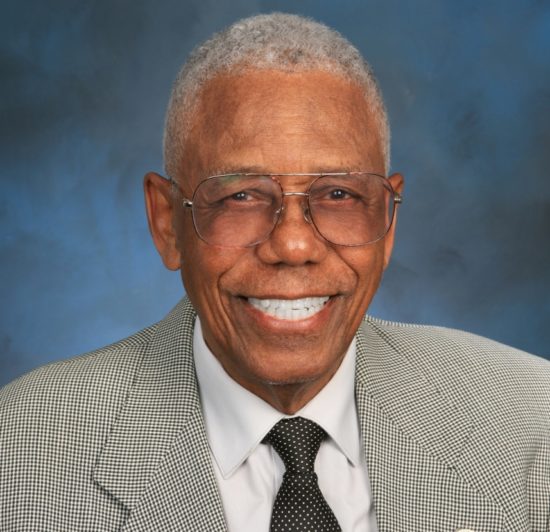

On the Ground Q&A: Nat Trives

On the Ground Q&A: Nat Trives

Nathaniel “Nat” Trives is a former mayor of Santa Monica (1975-77), the first African American to hold the position. Trives moved to the city in 1949 and has been nicknamed “Mr. Santa Monica” due to his widespread community involvement. Before becoming mayor, Trives served on the Santa Monica City Council from 1971-79. He is a former Santa Monica police officer–the first Black officer in the city to serve as a “generalist” and be allowed to police non-Black areas. Trives is also an emeritus professor of criminal justice at California State University, Los Angeles.

How do you remember May 31, 2020 in Santa Monica? What is important about that day and the moments that followed?

Santa Monica was besieged by a well-organized group of looters who synchronized their criminal activities using an organized protest march for cover. In other words, it was publicized that Santa Monica was going to have a big protest march, but these young people used cell phones and social media (to commit crimes). The march was in one section; the police were there in high numbers. And all of a sudden in the business community, you would see windows being smashed.

I was a former police officer and I taught 27 years in criminal justice. I watched it on television and was amazed (by the looting). I said, “this thing is so organized. It’s unbelievable.”

Our mayor at the time said there were boxes of sneakers all over the sidewalks–and it was better seeing the boxes than bodies. He said to think about if the officers had charged into downtown and tried to stop the looters; there could have been a shootout in a shoe store. I agreed with him. I’m not upset with the fact that Santa Monica police, after this thing had exploded, didn’t go out and shoot up everybody. However, we lost a lot of humility, and I’m not happy that our plans weren’t in place. I’m a strategic planner by habit. You always plan, and your alternatives have to be far-fetched, far-reaching. To think that Santa Monica wasn’t going to be a target in this thing was outrageous.

Following that day, what has gone wrong with efforts to establish civilian oversight of police in Santa Monica? Could this oversight have worked? What are the most pressing issues that you are concerned about?

At that time, I was following George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and too many others to even mention. Protests were going on all around the country. And to me, it was inevitable. There were going to be protests in Santa Monica. We have people here who are concerned about what’s going on in the country, particularly with people of color.

I was encouraged when the city allowed us to set up a series of recommendations that resulted in the creation of diverse groups designed to explore how to improve our police department. Now, I personally believe the initial response was thoughtful and would result in improved police and community relations. Creating an oversight commission with an Inspector General was encouraging. And more encouraging, the oversight commission was officially approved.

The goals that they set up in its creation–to promote partnership with Santa Monica police and best practices in community-oriented policing for fair treatment, safety, and the wellbeing of all–should have provided a body of work for experts to develop, recommend, and implement proposed reforms and for handling complaints regarding police conduct. These are all goals that I agree with. And the city could have publicized this and been one of the first in the nation to unanimously work with an oversight commission. But it’s fractured now. You couldn’t get a unanimous vote out of the city on anything.

Where has there been the most resistance to reform efforts? Why do you think this is the case?

The biggest enemy of genuine police reform is political interference. Reasonable people can come together and discuss controversial issues that will result in public policy that’ll be beneficial to all. I have presided over countless meetings as the president or chair of boards, commissions, task forces, you name it. I use the three T’s: Truth plus transparency equals trust. And when you have genuine trust, you can get more work done than you’d ever believe.

I’m a past president of the Santa Monica Police Department Union. I talked to the current union president and said, “look, you come to every meeting. You do not open your mouth. But I know that you have ideas and I know your board has ideas. And if we don’t know about them until it’s conflict time, it’s useless. Nothing happens.”

So, Santa Monica creates this wonderful commission, and now it becomes, “how many union votes do we have?” That’s not the discussion of the oversight commission. And I feel strongly about that. If we’re ever going to get through this, representatives from all parties who will be impacted by the new initiatives should have a seat and a voice.

Does being a former police officer give you perspective about reform challenges? How does this experience inform your views?

When I got into the police union, the reason I was successful is that I asked officers, “what do you want?” Well, they want money, they want security in their pensions, they want health benefits, very common things. And I said, “well, if you want those things, what are you going to give back to the community? And how are you going to treat the people that you’re writing a ticket for? And how are you going to treat people that you’re arresting?”

I feel I was always able to negotiate and talk to people about what their values were. And we had a great time during my tenure and we didn’t have any major cases come up against us. I measure the competency of a police department by the civil liabilities that are brought against the department for improper police action.

What should happen in Santa Monica to help the city’s residents achieve the goals of having a system of public safety that is fair, safe, and equitable for everyone?

We should allow the city to get its feet on the ground. Santa Monica got turned upside down during COVID. We have more vacancies in high-ranking leadership positions than I’ve ever seen–and I’ve lived in the town since 1949. The police department is also down a terrible amount of officers. Sure, the population is 90,000 plus, but on a given hot beach day, there could be up to 750,000 people coming through Santa Monica.

What’s going to happen with policing? We need to be able to regroup and bring stability to a place where people can trust that we’re going to do the right thing. You have to have a plan. You have to listen. Right now we have a lot of evidence on how to improve policing. And if we get the right analytical people and the right curriculum developed and so on, so forth, we can do something. But there are still people who want to dissolve the commission. And that’s the last thing I’d like to see, because to me, the dissolution of the commission would be an admission of failure. And we don’t need to fail. We need to improve.

This interview, part of the On The Ground: Santa Monica series, has been edited for length and clarity.

Photo source: MrSantaMonica.com