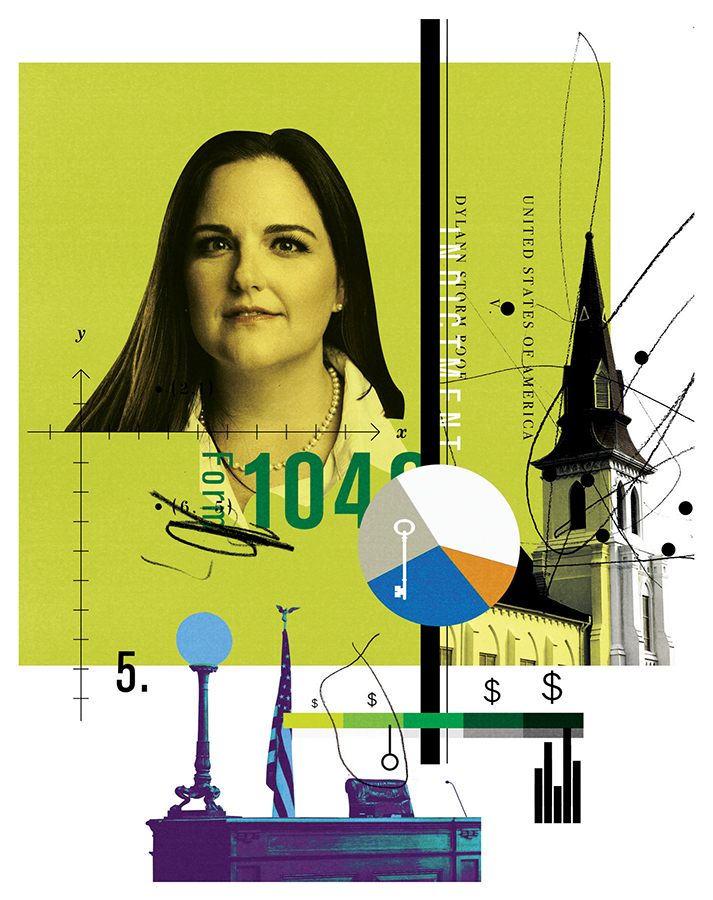

Adair Ford Boroughs

Finding and Filling Gaps as South Carolina’s U.S. Attorney

Growing up in a double-wide trailer amid the pine trees and cotton fields of Williston, South Carolina, Adair Ford Boroughs, JD ’07, never considered becoming a lawyer. In fact, she had never even met a lawyer.

The daughter of a carpenter and schoolteacher who lived “in the middle of nowhere” could not have imagined that one day she would be nominated by the president of the United States to serve as the top federal prosecutor for South Carolina. But in July 2022, Boroughs was sworn in as the U.S. attorney for the District of South Carolina, only the second woman to serve as the state’s top federal prosecutor. It wasn’t long ago, however, when she’d have said that possibility was about as likely as her flying to the moon.

Boroughs’ career trajectory has not yet taken her to outer space, but it has moved at warp speed. “I am known for going from zero to 60—when I decide to do something, I move fast,” she says.

How Boroughs ended up at law school is just one illustration of that determination and decisiveness.

Shortly after graduating summa cum laude from Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, she was teaching high school math in her home state. Her frustrations with local education policies and a chance conversation with a JD-holding, former South Carolina superintendent of education inspired her, on the spot, to think about law school. “I had the conversation in late fall, took the LSAT in December, and by the time I got my scores back, the admissions deadline had passed for most schools, but not Stanford,” Boroughs says with a laugh. Aside from a college trip to Missouri as a Harry S. Truman Scholar, she had never been west of the Mississippi.

At SLS, Boroughs laid the groundwork for a career as a public interest lawyer: editor in chief of the Stanford Law & Policy Review, head of the Stanford Public Interest Law Foundation, and leader of a student committee advising SLS on its Loan Repayment Assistance Program policies. It was all in furtherance of her goal of returning to South Carolina. “I love my home and I feel very rooted to the people I grew up with. I’m the kid in my high school who got to go out into the world, and I feel a very deep obligation to bring those experiences back home.”

Those experiences have helped Boroughs shape her priorities as U.S. attorney. “I’m directing resources to evidence-based prosecution models that show actual reductions in violent crimes,” she says. “Our goal is to take cases where the prosecutions don’t just punish the person who committed the crime, but which will also result in a broad, positive community impact. We work with the focused deterrence model, which is focused on using community partnerships to fight crime.” In addition to combating gun violence, prosecuting cases that involve causes of action only available at the federal level—such as hate crimes—are her top priorities.

Mind the Gap

“No matter how busy she might be—and she was very busy with leadership positions and excelling at her studies during law school—Adair was, and is, focused on filling gaps, seeing where there is a need and then stepping up,” says Diane T. Chin, SLS’s associate dean for public service and public interest law. “Her leadership style is informed by her kindness and generosity. She was frequently the smartest person in the room, but she invited participation, listened, and always conveyed an openness to hearing others out.”

Boroughs’ first post-SLS position was at the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C., litigating—and winning—tax shelter cases (having been a math major was helpful, she says). A few years later, with trial experience under her belt, it was time to return to family and community in South Carolina, along with her husband and daughter. (The couple now has two girls, ages 11 and 8.) A federal clerkship in Charleston took her into the maw of the death penalty case against Dylann Roof, the white supremacist who killed nine people attending a church Bible study in 2015. “The judge recognized the profound need for timely closure and justice in the community, and so we kept that case moving much faster than most death penalty cases. We worked an insane amount of hours,” says Boroughs.

“Adair was a brilliant law clerk, excellently trained in legal research and writing with uncommon, good judgment,” Judge Richard Gergel, U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina, remembers. “She never forgot we were administering a system of justice rather than simply applying cold legal principles.”

The next phase of her career was another example of identifying a gap and mobilizing to fill it. With a friend and co-federal court clerk, Boroughs established Charleston Legal Access, South Carolina’s first and only nonprofit, sliding-scale law firm that serves an often-overlooked—and huge—segment of the population: low-income individuals whose resources disqualify them for legal aid but who nonetheless cannot afford a lawyer.

“This particular gap in the provision of legal services was something I felt very personally,” Boroughs says. “We set out to represent people like our dads, people who might be working in retail or construction who could never pay a lawyer $250 an hour if they have a landlord dispute or a car that was wrongly repossessed. No one was helping these people and there was such a need.”

Funded by a combination of donations, grants, and client fees, Charleston Legal Access today boasts nine staff members and recently moved into larger office space.

Politics and Policy

With the nonprofit on firm footing, Boroughs began to hear the siren call of politics. Her 2020 bid to unseat a 10-term U.S. congressman was not successful, but it put her on the national radar. Next came a call from Representative Jim Clyburn, asking if she might like to be put forward as a Biden nominee for U.S. attorney.

“I am the sixth person in the U.S. attorney chair in the last two and a half years, so there has been a lot of work to do,” she says. One of her first tasks was to address yet another gap: “I was the kid who could never afford to take an unpaid internship, and so I’ve always been keenly aware of the huge advantages internships bring to young people who can afford to do them,” she says. “We are now one of just two districts in the United States that provide paid internships. Making this change was very important to me. After all, we are the Department of Justice. A big part of justice is basic fairness, right?” SL