California Prisons: The Cost of Ignorance

It has begun to enter public consciousness that the United States now houses more of its constituents as guests of the government—in jails and prisons—than any other nation. In this regard we not only exceed our “peers” (Australia, Canada, Japan, and Western Europe) by several hundred percent, we exceed all countries for which we have records: Russia is a distant second. It is also obvious that California has one of the most dysfunctional prison systems in the nation. The problem in the Golden State is not the overall rate of prison inmates per capita (we are average when compared with other states) but overcrowding. California is now close to 200 percent of its design capacity. Today the system faces a perverse pincer movement of economic, political, and legal forces: The governor is desperately seeking ways to reduce the inmate population to alleviate the budget crisis; the legislature resists any prisoner release out of fear that a release threatens public safety and is politically toxic; and a special federal court has ordered a 25 percent population reduction to remedy unconstitutional conditions.

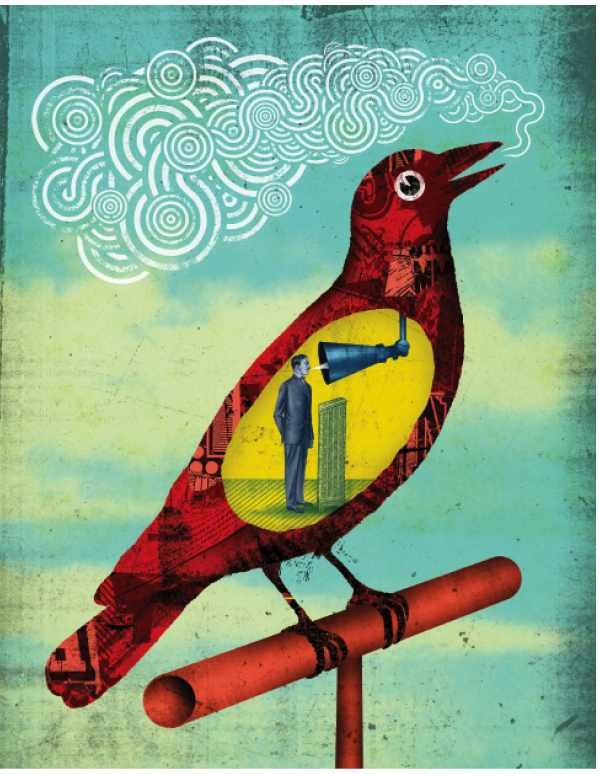

With prison conditions now prominent in the public’s consciousness, the need for empirically validated, data-driven criminal justice policies and programs has never been greater. The Stanford Criminal Justice Center (SCJC), established in 2004, promotes the study of criminal law and the criminal justice system, with an eye toward sharing the best data with policy-makers and devising a way to move forward. Over the past three years, the center has sponsored, with support from The Pew Charitable Trusts, a series of “Executive Sessions” on California sentencing and prison reform, involving dozens of leading scholars and key public policymakers. Their work influenced the recently passed Corrections Reform Bill and the structure of California’s proposed sentencing commission. We believe that this kind of data sharing—with scholars and policymakers coming together to find solutions—is essential if the state and indeed the country are to solve these seemingly intractable challenges.

This past August, the term “overcrowding” took on a more salient form when prisoners in the California Institution for Men at Chino rioted, causing millions of dollars in damage and serious injuries—though fortunately no fatalities. The prison riot as a manifestation of overcrowding has itself become a subject worthy of examination for the SCJC.

That inquiry will focus on the specific context in which “modern” riots take place. Prison riots have actually become less common in the United States in recent decades. Through the early 20th century, riots were often responses to gratuitous brutality by prison staff acting outside any legal constraint. The last epidemic of riots dates back to the 1970s, when riots were often organized rebellions against state authority and strongly associated with the political upheavals and racial battles that were occurring in U.S. society more generally. Since then, judicial controls to enforce prisoners’ rights and enhanced professional standards and training for prison staff have led to the relative quieting of U.S. prisons. Where we do see upheavals, like the one in Chino, they usually are not organized as rebellions against authority—except in the indirect sense that the physical and psychological pressures of state-tolerated overcrowding make daily wear-and-tear tensions among prisoners all the more volatile. To the extent the riots are organized, the organization runs along another dimension—gangs. Especially in California, the prisoner population mirrors urban life outside prison in terms of sharp rivalries among gangs that are in turn significantly correlated with race and ethnicity. So as long as we have gangs outside prison, we will have them inside, with the two realms reinforcing each other and in-prison leaders coercing new inmates into “membership.”

Until prison crowding is addressed, prison administrators must use available resources to sort prisoners in such a way as to reduce tensions, to isolate the most violent inmates, and generally to control the physical environment of prison real estate to ensure security. And these days, prisons have a pretty rich array of managerial and technological means of doing so, if space and time to undertake these measures permit. But the California situation presents some special problems. The riots in Chino took place in the ironically named “reception center” in the facility. At any time, a large fraction of prisoners are in open double- and triple-bunked dormitories where new prisoners live while awaiting long-term designation (think 600 high school students sleeping and hanging around for weeks in the gym). These reception centers can be a managerial nightmare. The physical environment is very hard to secure and, worse yet, their populations are often a chaos of inflow and outflow. Under California’s unusual parole laws, many new prisoners are parole violators returned to prison for conduct that might be new crimes or so-called administrative violations of various behavioral conditions of parole (i.e., missing a rehab session or changing residence without permission). These revokees who come back to the reception centers might actually be released from prison without ever entering a cell block. Other new inmates who are in for a longer time might stay extra months in the reception center because no cell block space is available. Those released directly from the reception center too often come right back to prison in a few weeks because of new offenses or violations. Under these circumstances, the most able and fair-minded prison administrator finds it difficult to provide security and order, and it is sometimes the prison riot that provides public confirmation of that difficulty.

And now let us return to the gang problem. It is a tragic fact that gangs sort themselves out by race or ethnicity. Until a few years ago, the prison was the last remaining place in our society where deliberate racial segregation was legally tolerated. Then the Supreme Court ruled that under the Equal Protection Clause prisons no longer could be such an exception. The Court has given California a window of time to take all feasible measures to eliminate race-based segregation, but translating that mandate into a sensible system is a daunting legal and administrative challenge.

Meanwhile, just as in-prison gang rivalries continue when inmates are released to their home cities, so the behavioral effects of overcrowding that explain riotous outbreaks within prison can exacerbate the individual behavioral problems that offenders often exhibit after release, if the correctional system is just an “in-out-in” warehouse without any provision for reentry guidance. And, ironically, the much-decried lack of any reentry counseling or preparation prisoners get before release is itself a function of overcrowding: Even in the rare instances where prisons have staff or resources for such programs, the physical spaces in which these programs might be conducted have often been given over to overflow prison beds.

Prison riots, though less frequent and far less deadly than in the past, are a problem demanding attention on their own. But as research on the contemporary prison riot evolves, it will also serve as a lever for policymakers to understand the ills of the U.S. correctional system more generally.