Does Media Consolidation Stifle Viewpoints? How the Supreme Court Can Provide an Answer

When Rupert Murdoch launched his bid for Newsday this year at a price of $580 million, consumer groups were up in arms. Common Cause assailed the proposed acquisition as “a step back that will hurt our democracy.” S. Derek Turner of Free Press charged, “New York, like the rest of America, needs more media choices, viewpoints, and competition—not more consolidation.” And when the Federal Communications Commission considered related matters in 2002, more than half a million comments flooded the agency. Yet for all the wrangling, is it true that media consolidation stifles viewpoints?

The Supreme Court, it turns out, can help answer this question. But not in the way you might think.

For decades, the FCC has maintained a set of ownership regulations that limits the number of media outlets one entity can own. Newspapers, such as Murdoch’s New York Post, come under the purview of the FCC’s “cross-ownership rule,” restricting common ownership of newspapers and broadcast stations in a market.

Most of federal law on the matter is predicated on an assumption that consolidation will reduce so-called “viewpoint diversity.” Put another way, viewpoints may converge with common ownership. Yet economic or communications theory doesn’t squarely provide a conclusion to that premise. Over the past decade, recognizing the theoretical ambiguity, the courts and the FCC have increasingly required empirical evidence in support of this convergence hypothesis.

The trouble is that the evidence so far has been, well, flimsy.

The concept of viewpoint diversity, as the courts have recognized, is elusive. And when, in 2002, the FCC commissioned a handful of empirical studies on the connection between ownership and viewpoint diversity, it didn’t find much. Indeed, this elusiveness led Commissioner Jonathan Adelstein to conclude that the FCC’s proceeding was “like submitting a high-school term paper for a PhD thesis.”

But the lack of conclusive evidence may be the result of either poor measurement of viewpoints or because ownership and viewpoints aren’t directly related. Little consensus exists as to which story is right.

Fortunately, rapid advances in statistics are making rigorous assessment of the convergence hypothesis possible. While “viewpoint” is an elusive concept, it does have observable consequences—in the same way that elusive concepts of “ability” or “intelligence” have observable implications. The virtue of standardized tests, such as the SAT, is that each test answer can be viewed as a noisy indicator of a student’s underlying intelligence. Similarly, as political scientists have recognized, we can summarize legislators’ views based on their voting records on common bills. The crucial step is collecting information about answers (or votes) to common questions.

Where might we look for answers to common questions about viewpoint diversity when newspaper editors don’t sit for a test, such as an SAT? Here’s where the Supreme Court comes in. Supreme Court justices vote on the merits of roughly 100 cases each term. And newspapers regularly editorialize on these decisions. Connecting newspaper editorials to the opinions of the justices solves the difficult problem of quantifying editorial viewpoints, which the FCC has recognized as a crucial component of viewpoint diversity.

With a large research team at Harvard and Stanford, we collected every editorial position on a Supreme Court decision by the top 25 newspapers from 1994 to 2004 (roughly 1,600 editorial positions) and coded these as agreeing with the majority or minority on the Court. Supreme Court cases are ideal for this study as they represent a staggering array of discrete issues.

With some refined statistical adjustments, this evidence allows us to scale newspapers in terms of their comparability on a single dimension. One can think of it as running from “liberal” to “conservative.” The scale tells us how each newspaper would have voted as a 10th justice and allows us to assess how viewpoints change with mergers and acquisitions of newspapers. Essentially, the results reveal what a reasonable reader would infer after reading the editorial pages of 25 newspapers and the opinions in some 500 (nonunanimous) Supreme Court cases over a period of 10 years. It is in this sense that the Supreme Court is helping us learn about newspapers.

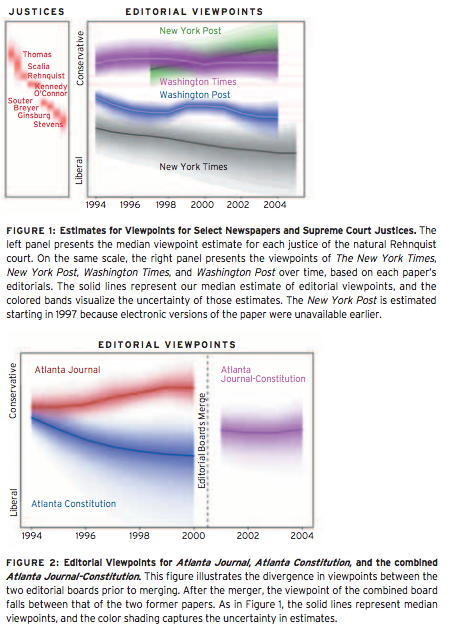

Figure 1 presents some sample results for The New York Times, New York Post, Washington Times, and Washington Post. The results quantify editorial viewpoints (and uncertainty as represented in the bands) meaningfully: The overall probability that The Washington Post is to the right of The New York Times is nearly 1. The New York Post’s phantom jurisprudence most resembles that of Justice Scalia. More importantly, our analysis allows us to examine the dynamic evolution of newspapers. The New York Times, for example, has been consistently trending to the left of Justice Stevens.

So what happens with a newspaper merger? One important test is the merger of the editorial boards of the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution in 2001 to form The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. This merger appears to corroborate the convergence hypothesis: The Journal-Constitution’s viewpoint lands squarely between the two prior papers. But they arrive at that middle position in an unusual way.

In 1995, both the Journal and the Constitution supported the five-justice majority in United States v. Lopez, which struck down a federal statute prohibiting guns in school zones. But shortly thereafter, the papers diverge considerably. In 1999, for example, the Constitution argued that the court “ruled wisely and well” when it found that a school could be liable for discriminatory acts committed by students, while the Journal charged that the decision “opened yet another floodgate to lawsuits.” The viewpoints of the editorial board members differed so sharply between the two papers that the merged Journal-Constitution faced serious difficulty forging a consensus position on cases. As a result, around 2006 the paper became the first major U.S. newspaper to disband the practice of unsigned editorials. The individual columns again came to reflect diverging liberal and conservative viewpoints in line with those followed prior to the merger. Paradoxically, then, the merger may have unified Atlanta’s readership, with the net effect of exposing more readers to more viewpoints.

Of course, the Atlanta experience may be unique. Examining all acquisitions occurring between the newspapers in our data, effects were varied and depended on the circumstances of the ownership change: for chain acquisitions (e.g., Hearst’s acquisition of the San Francisco Chronicle), editorial viewpoints remained stable; but after The New York Times acquired The Boston Globe, the papers switched positions.

Our analysis suggests three lessons. First, consolidation does not inexorably cause convergence or divergence in viewpoints.

Second, our analysis points to the promises and perils of empirical assessment in law and regulation. Using tools developed across applied statistics allows thorny questions of public policy and regulation to be examined with data. If, for example, consolidation systematically diversified viewpoints, there would be little use in maintaining various ownership regulations.

On the other hand, such inquiry isn’t easy. Courts and agencies shouldn’t expect too much. Our approach, for example, does not assess viewpoints expressed in news reporting, nor can we realistically examine the effects of vast changes of federal regulation. Judges and policymakers don’t necessarily have the luxury of making decisions after the data have been systematically gathered and analyzed. This difficulty of evaluation suggests a type of precautionary principle: Incremental, as opposed to wholesale, modification of federal regulation facilitates policy evaluation.

Last, our study sheds light on and informs what factors the FCC should consider in applying its waiver policy to the likes of Rupert Murdoch. Whether media consolidation stifles viewpoints may ultimately turn on the minutiae of the acquisition: e.g., the terms of organizational restructuring, guarantees of editorial independence, and employment conditions.

That’s the trouble when you face the data. It might show you that the devil’s in the details.

This piece was co-written for the Stanford Lawyer by Daniel E. Ho, assistant professor of law and Robert E. Paradise Faculty Fellow for Excellence in Teaching and Research, Stanford Law School; and Kevin M. Quinn, associate professor, Department of Government and Institute for Quantitative Social Science, Harvard University. The article is forthcoming in the Stanford Law Review and is available at http://dho.stanford.edu/.