Law of Democracy

As a Justice Department official last year, Pamela Karlan walked with President Obama and others across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, to mark the 50th anniversary of the “Bloody Sunday” march that culminated in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the landmark civil rights legislation that outlawed widespread and persistent discrimination against African-American voters.

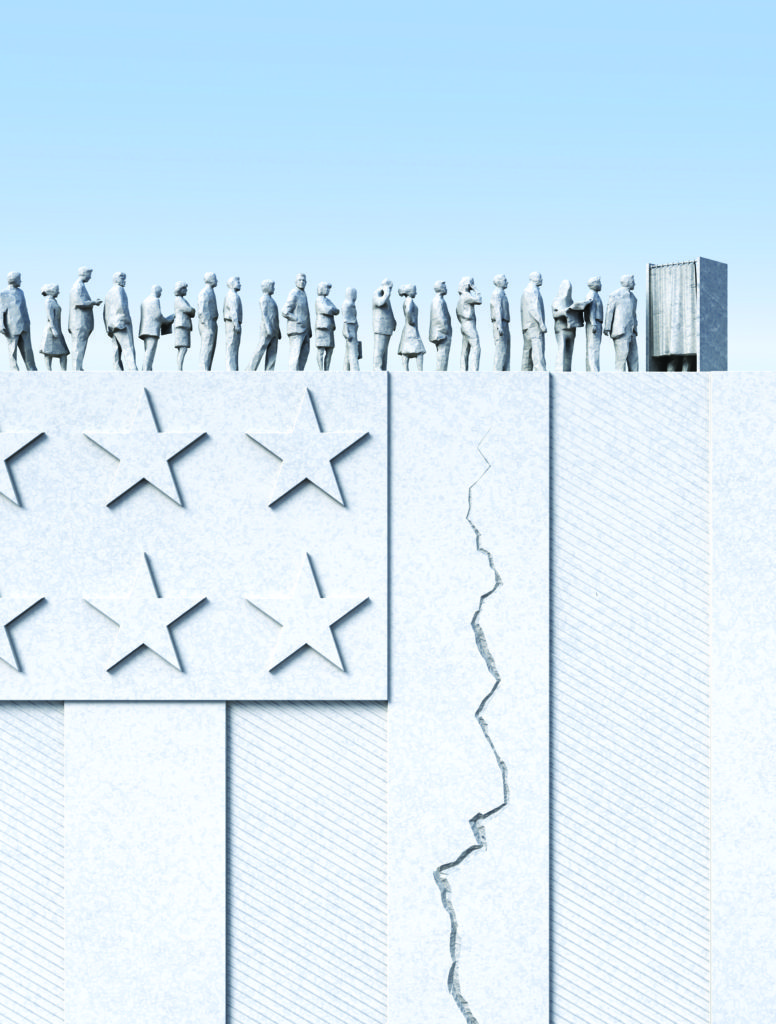

But Karlan and other advocates know well that the battle for voting rights is far from over, a fact that has been thrown into sharp relief this election season. Seventeen states have enacted new restrictions on voting that will be tested in November for the first time in a presidential election.

The restrictions include new hurdles to registration and cutbacks on early voting as well as strict photo identification requirements that critics say operate like the literacy tests banned by Congress a half-century ago. The Justice Department has been going to court to challenge some of the new restrictions, but with the U.S. Supreme Court having dismantled a key part of the Voting Rights Act, the department lacks some of its traditional ammunition.

“I felt like crying sometimes when I sat in the courtroom and listened to voter witnesses who testified about how difficult it had been for them to vote,” says Karlan, who was on leave from the law school in 2014-2015 while serving as deputy assistant attorney general overseeing voting rights cases.

How these battles are resolved remains to be seen. But they are illustrative of how law and legal issues have come to occupy center stage in presidential election years. And this season there is no shortage of drama. Aside from new voting laws, there are disputes over the drawing of election maps and charges of gerrymandering erupting in battleground states. Much of that reflects the partisan rancor that has come to define American politics in recent years.

With new voting machines purchased in the wake of the 2000 Florida recount nearing the end of their useful lives, the nuts and bolts of administering elections remains a weak link in the system.

Among legal academics, it’s all part of the field called the law of democracy, which, besides what happens on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November, focuses on broad questions about the institutions that shape American democracy, including the right to vote, to associate with a political party, and to have equal representation in government.

A voting rights litigator, scholar, and teacher, Karlan, the Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Professor of Public Interest Law and co-founder and co-director of the Supreme Court Litigation Clinic, literally wrote the book on the subject nearly 20 years ago with the publication of The Law of Democracy: Legal Structure of the Political Process. She is a sought-after legal advisor for civil rights groups and other organizations involved in the political process. She is also renowned for her fearlessness, compassion—and wit. She is probably the only legal scholar ever to compare redistricting with sex, because, as she wrote in an article in the Stanford Law Review, they both involve “lofty goals, deep passions … [and often] … somebody getting screwed.”

“Pam is always called one of the founding parents of election law, but I think of her as its rock star goddess,” says Heather Gerken, a professor and election law expert at Yale Law School. “She is the only person I know capable of making election nerds seem cool. We all root for her to be nominated to the [Supreme] Court. Even if the odds are against her given her liberal views, the confirmation hearings would be spectacular. HBO would pick them up.”

A former star student of Karlan’s, Nathaniel Persily, JD ’98, the James B. McClatchy Professor of Law, who joined the Stanford Law faculty in 2013, brings the fresh perspective of a political scientist to the field, applying an empirical rigor to the issues. He has developed a reputation as an honest broker, drawing nonpartisan redistricting maps and advising a presidential commission on election administration reforms.

Persily recently finished a book on solutions to political polarization. One idea he raises: Reform campaign finance laws to strengthen the ability of national parties to raise money and compete against outside groups that are more extreme and less accountable. [Persily was also awarded a 2016 Andrew Carnegie Fellowship, which he plans to use to continue his research into how big data and the

Internet will change the ways candidates campaign, parties mobilize supporters, and voters cast their ballots. See sidebar on p. 24 for more on this research.]

“There is no law school in the country that has a more powerful combination of election law professors than Stanford,” says Richard Hasen, a law and political science professor at the University of California, Irvine, School of Law and author of the influential Election Law Blog.

Certainly, few areas of the law have grown so much in recent years, both in academic stature and in the popular culture. Not too long ago, “election lawyers were like Major League umpires,” says J. Gerald Hebert, a longtime Justice Department voting rights attorney who is now executive director and director of litigation at the Campaign Legal Center, a Washington nonprofit that specializes in voting rights cases. “They were oftentimes on the field. But you only noticed them when they did something wrong.”

The voting problems exposed in the 2000 election and the furor over the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore transformed the landscape. Voting patterns in subsequent elections showing that Democrats benefited from high turnouts and Republicans from low turnouts touched off a partisan war over election administration. The result: almost nonstop election year litigation, with armies of lawyers as central to the process as campaign volunteers and precinct chairmen.

Karlan recognized early that this was fertile terrain, collaborating with former Yale Law School classmate Samuel Issacharoff, then a professor at Columbia Law School, and Richard Pildes, then a University of Michigan Law School professor, on the first edition of The Law of Democracy in 1998. It was well received. Obama used the text when he taught election law at the University of Chicago Law School. After Bush v. Gore, interest exploded, with the role of money in politics and the power of technology providing grist for future editions.

Persily, who in 2015 joined The Law of Democracy team as a co-author, took Karlan’s voting rights class in 1996, when he was a second-year law student. In his third year, as president of the Stanford Law Review, he organized a symposium on voting rights that attracted leading scholars from around the country. He did all this while he was also a PhD student at Berkeley.

“What Nate brings to the book are, first, formal training as a political scientist; second, a lot of expertise in campaign finance, redistricting, and election administration issues; and third, a fresh eye,” Karlan says.

One of Persily’s focuses has been on what he calls “armchair” assessments of public opinion, by members of the Supreme Court, that have shown up in some recent election law cases.

A number of the justices, for example, have indicated they believe that voter ID laws increase public confidence in the electoral system, an intuitively appealing idea that has been a major selling point of proponents of these laws.

Persily and Harvard government professor Stephen Ansolabehere decided to survey voters about how they actually felt about the laws—and couldn’t find any evidence to support what the justices were saying. Voters in states with tough ID laws, they discovered, were no more or less apt to have confidence in the system than those in states with less-restrictive laws.

Judges have expressed mixed feelings about such findings. A panel of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, upholding a restrictive voter ID law in Wisconsin, dismissed the Persily-Ansolabehere analysis because it had not appeared in a “refereed scholarly journal,” even though it had appeared in the Harvard Law Review. Another circuit judge, Richard Posner, came to the authors’ defense.

“So much for law reviews,” Posner wrote in a dissenting opinion. “And what about Supreme Court opinions? They are not peer-reviewed either.” Posner, who years earlier voted to uphold a voter ID law enacted in Indiana, concluded that some of the evidence of fraud that supporters had used to justify the Wisconsin law was “downright goofy, if not paranoid.”

“Nate’s background brings to light empirical questions you might overlook,” says Bruce Cain, one of Persily’s doctoral advisors, who is now the Spence and Cleone Eccles Family Director of the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford. “He’s an important bridging person.”

Lately, election law lawyers have been very busy. This term, the Supreme Court has had four major election law cases including one that challenged, unsuccessfully, how states have interpreted the “one-person, one-vote” principle for purposes of drawing legislative districts. At present, virtually all states use total population, which includes non-voting immigrants, prisoners, and children.

The plaintiffs were Texas residents, who alleged that the state’s method of counting all persons dilutes the voting power of citizens residing in districts that are home to smaller concentrations of non-voting residents.

Persily and Cain submitted a friend-of-the-court brief defending the use of total population as the basis for redistricting. They also made a more pragmatic argument: The data that would allow states to redistrict on the basis of eligible voters simply did not exist. The Court’s decision, while it did not require Texas to redraw its districts, leaves for another day whether a state can choose to draw lines based on citizenship.

A series of lawsuits in lower courts, meanwhile, challenge the alignment of congressional seats, reflecting the upper hand that Republicans got in state legislatures in the 2010 elections and in the once-in-a-decade redrawing of election districts that followed.

“For them, the best political strategy has been to concentrate as many minority voters as possible in majority non-white districts,” says Karlan, “which leaves remaining districts whiter and more heavily Republican.”

But that has left Republican-drawn election maps in such states as Alabama, Virginia, and North Carolina under attack—battlegrounds just months before voters are to go to the polls in November. Mapmakers in North Carolina have been scrambling after a federal court in February held that congressional district lines drawn in 2011 reflected an unconstitutional racial gerrymandering because they packed

African-American voters into just two districts.

Ironically, two decades ago, challenges to irregularly shaped majority-minority districts involved plans crafted by Democrats. The lines were designed to spread minority voters across districts to shore up the seats of white Democratic incumbents in adjacent majority-white districts in the face of declining support among white voters in the South. Now, in a turnabout, Democrats and voting rights advocates are using those same precedents to attack Republican-drawn lines that they see as excessively concentrating minority voters.

“It’s an illustration of how lawsuits that focus on race have become a sort of stalking horse for more political fights,” Karlan says.

How far parties that dominate can go in discriminating against their political opponents when they draw election maps is a large, and unresolved, issue. Partly because of redistricting, Republicans maintained their majority in the House in 2012 even as Democrats won more votes nationally. A replay is possible this fall. But the Supreme Court has said the problem is one for individual states to fix. Persily believes states should be able to experiment with alternatives, such as independent redistricting commissions, although beyond California and Arizona the idea has not gotten much traction.

To voting rights veterans like Karlan, the spate of new restrictions on voting evokes a sense of déjà vu. As a private lawyer in the 1980s, she helped strike down at-large election systems in Alabama that had the effect of denying African-Americans representation on dozens of school boards, county commissions, and municipalities.

Today, “we’re back to litigating ‘first-generation’ cases, challenging state laws that actually make it harder for people to vote,” she says, referring to recently enacted voter ID laws, restrictive registration practices, and cutbacks to same-day registration or early voting. “As the Jim Crow era seems further and further in the past, there’s a mistaken sense that civil rights era laws like the Voting Rights Act are no longer necessary.”

In 2013, the Supreme Court decided, in Shelby County v. Holder, that a key provision of the Voting Rights Act should no longer be used. The provision, known as Section 5, had given the Justice Department special oversight of elections in nine mostly Southern states with a history of discrimination. The high court’s ruling meant those jurisdictions no longer had to get approval from Justice Department officials before enacting changes in voting. The decision propelled lawmakers in some of those states to pass new restrictions—and left voting rights groups and the Justice Department scrambling to respond.

“There was a wave of new laws making it harder to register to vote or to cast a ballot, unlike anything we had seen in decades,” recalls Dale Ho, the head of the ACLU Voting Rights Project. “Pam is one of the first people I turned to, to figure out what our argument should be as to the proper legal standard for these challenges.”

Before long, Karlan got a call from Attorney General Eric Holder, who asked her to help spearhead voting rights cases at the Justice Department.

“We were faced in relatively short order with a variety of different restrictions on voting around the country,” says Vanita Gupta, principal deputy assistant attorney general and head of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division.

“Pam came in to oversee our critically important post-Shelby Section 2 litigation,” Gupta says, alluding to a part of the Voting Rights Act that bans voting laws that have a discriminatory effect. “Her thinking on those issues, her advocacy on those issues, have been vitally important.”

Siding with the Justice Department and private plaintiffs, a district court struck down a voter ID measure in Texas. A panel of the Fifth Circuit agreed that the measure violated Section 2 because it had a discriminatory impact on African-American and Hispanic voters, but the case has been taken en banc.

The department also filed a lawsuit over a wide-ranging law in North Carolina that imposed limits on early voting, prohibited people from registering and voting on the same day, and ended a practice of preregistering teenagers before they turned 18. While rolling back measures that had made voting easier, the law also imposed a strict voter ID requirement that the Justice Department said would make voting harder. A district court upheld the law, but an expedited appeal is now pending in the Fourth Circuit.

Karlan is constrained from talking in detail about her time at the Justice Department, but she said it was a privilege to work there. The experience also marked a reunion of sorts. The team leader for the North Carolina trial was career Justice Department lawyer Bert Russ, JD ’97, who took her voting rights class at Stanford. Her first student research assistant, Chris Herren, now serves as the department’s career voting rights section chief, and a third student, Alex Tischenko, JD ’14, was recently hired by the Justice Department honors program, assigned to the voting section.

“I was struck by the commitment, from Eric Holder and [current Attorney General] Loretta Lynch down to the most junior lawyers on the teams, to vindicating the right to vote,” Karlan says, adding that stories she heard in court of citizens trying to exercise their right to vote in the South were equally compelling. “The faith that these citizens, many of whom lead lives of grinding poverty, showed in the promises of American democracy really inspired me.”

Some aspects of voting this year may be easier to navigate. Long lines at polling places in the 2012 election prompted President Obama to appoint a bipartisan commission to identify reforms, including Obama’s 2012 campaign lawyer, Robert Bauer, and Ben Ginsberg, the lawyer for Mitt Romney’s campaign, as co-directors. Persily, with extensive firsthand experience including serving as a court-appointed expert to draw legislative districting plans for Georgia, Maryland, and New York and as special master for the redistricting of Connecticut’s congressional districts, took on the commission’s senior research director position, bringing together the relevant research and then writing the report that was submitted to President Obama.

“Nate quickly became the consensus choice,” Ginsberg says.

The commission heard from a cross-section of Americans about challenges they faced in voting, from persons with handicaps to Alaska Native villagers. Seeking out solutions, they took a trip to Disney World to see how the theme park works its magic managing long lines. Persily remembers checking out a new area at the popular Dumbo the Flying Elephant ride, where children could play while waiting their turn for the ride. One takeaway: Keeping people occupied and comfortable is a good antidote for long lines.

The commission made a series of recommendations and, while there is a long way to go, several have already been embraced. Some 30 states are now allowing citizens to register to vote online, and a growing number are sharing data in an effort to clean up voting and registration lists. Some are experimenting with managing those long lines: Los Angeles County has been testing a system where voters record their preferences on their cell phones and then input them once they reach the voting booth.

The commission’s recommendations were presented to President Obama and Vice President Joe Biden in a January 22, 2014, meeting at the White House. “Given how poisonous the partisan atmosphere in Washington was and is,” Persily recalls, “they really saw this as a glimmer of success.” SL

Rick Schmitt, an attorney and former staff writer for the Wall Street Journal and Los Angeles Times, is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C.