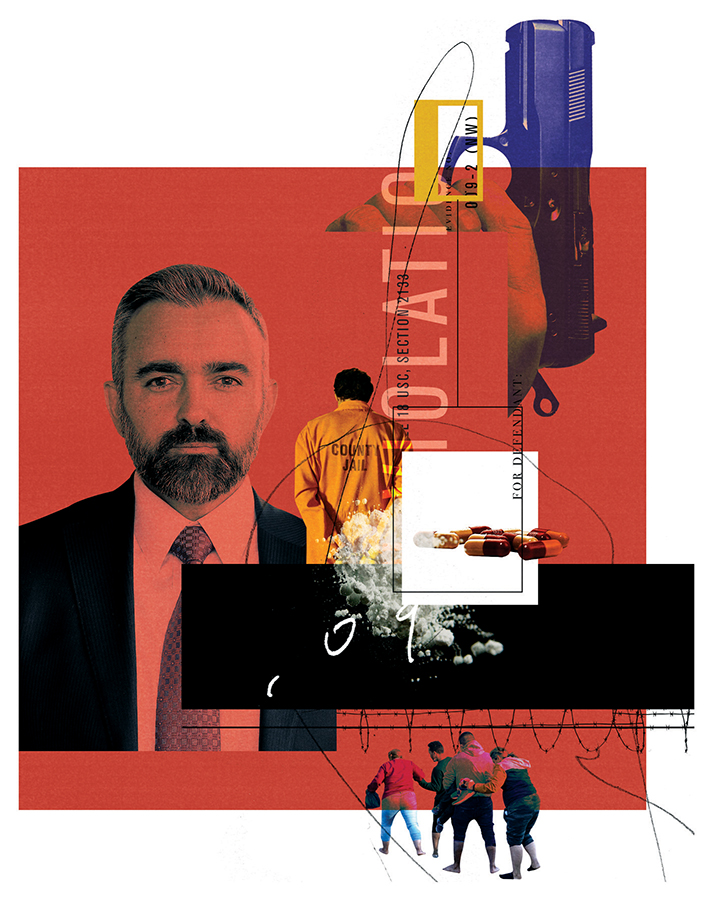

Raúl Torrez

New Mexico’s New Attorney General

When Raúl Torrez, JD ’05, started his first post-law school job as an assistant district attorney outside Albuquerque, New Mexico, he immediately felt at home. After all, some of the staff members in the office had known him since he was a baby.

“When I graduated from Stanford Law School, and all my friends were going off to these high-paying careers in New York and San Francisco, I took a job for $37,000 in the Valencia County district attorney’s office, where my father had started practicing law when I was a little boy,” says Torrez, who was sworn in as New Mexico’s 32nd attorney general in January 2023. “There were still a few paralegals and secretaries there who used to babysit me, so they were there to welcome me back as an attorney.”

And Torrez was delighted to be back. His years at Harvard, the London School of Economics, and SLS, as well as a stint in Los Angeles working for the Cesar Chavez Foundation, had given him a world-class resume, but there was only one place in the world he wanted to be: New Mexico, where both sides of his family have lived for generations.

“My parents always made sure I remembered where I was from,” he says. “They were both public servants and my role models. My mom was a school teacher and my father was a career federal prosecutor who spent his life handling complex criminal cases, often against very violent and dangerous people, including cartels. When I was a kid, he did not even want me to come watch him in the courtroom given the nature of the cases.”

Even if he was rarely able to see his father in action, Torrez knew he wanted to do what he did: try cases, fight crime, and use his legal training to help his home state confront its challenges.

With the exception of a short detour to Washington, D.C., as a White House Fellow in the Obama administration from 2009 to 2010, Torrez has worked in state and federal prosecutorial roles in New Mexico since graduating from SLS, including in the U.S. attorney’s office in Albuquerque and as the elected district attorney for Bernalillo County, the Albuquerque area’s main county. Torrez announced his candidacy for state attorney general in May 2021. He defeated the New Mexico state auditor for the Democratic nomination and went on to beat his Republican challenger in the general election.

He credits SLS’s Loan Repayment Assistance Program (LRAP) for allowing him to choose a public service career path that led to his current position as New Mexico’s top law enforcement officer, what he calls “the best job in the world.”

“LRAP was a large part of why I chose to go to Stanford,” Torrez says. High points of his time at SLS included the mock trial program, Professor George Fisher’s evidence class, and having former SLS professor Mariano-Florentino “Tino” Cuéllar, (MA ’96, PhD ’00), who went on to serve on the Supreme Court of California, serve as his adviser on a research paper. “Tino had a huge impact on me,” Torrez says. “He showed me how to chart a career that could go back and forth between public policy, politics, and the law.”

A Focus on Civil Rights

On a credenza in Torrez’s office, nestled between photos of his wife, Nasha, also an attorney, and their two children, is a picture of a smiling baby named Marcelino.

The photo has been there since Torrez’s early days as an assistant district attorney. Marcelino, a severely brain damaged “shaken baby,” was the victim in the first case Torrez prosecuted. “In law school you learn some of the mechanics of practicing law, but until you are face to face with a victim, you can’t even begin to understand what it takes, mentally and emotionally, to advocate for them,” he explains. “Especially when you are talking about child abuse. I used to volunteer to do the safe house interviews, where I would drive up to Albuquerque and listen to the disclosures of young children disclosing sexual assault, physical abuse, neglect and things like that. That really took a toll on me.”

But it also galvanized him.

“Unfortunately our state does not rank highly in terms of the well-being of children, and so Raúl has always put children at the center of his agenda,” says Adolfo Méndez (BA ’94), special counsel at the attorney general’s office, who has worked alongside Torrez since he was the Bernalillo County DA. “One of the first things he did as attorney general was to push for legislation to create a civil rights division of the AG’s office, with a focus on protecting the civil rights of children, particularly at-risk kids who are in the foster care system or who are victims of abuse and neglect. New Mexico state agencies have a long history of failing to adequately protect these children.”

New Mexico Senate Bill 426 passed on March 18, 2023, but Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham subsequently pocket vetoed the legislation, putting on hold Torrez’s vision for a Civil Rights Division within the New Mexico Office of the Attorney General.

“In law school, you learn some of the mechanics of practicing law, but until you are face to face with a victim, you can’t even begin to understand what it takes, mentally and emotionally, to advocate for them.” —Raúl Torrez, JD ’05

Julie Chavez Rodriguez, a senior adviser to President Biden and director of the White House Office of Intergovernmental Affairs, which engages state, local, and tribal governments to address issues impacting their communities, worked with Torrez at the Cesar Chavez Foundation in the early 2000s and has continued to consult with him over the decades. “Raúl is a natural-born leader who thinks deeply about the issues,” she says. “I greatly value his perspective, especially now that he is one of my constituents. His forward-looking approach and ability to move decisively—for example attempting to establish the new Civil Rights Division within just a few months of being elected—are inspiring.”

Data-Driven and “Balanced”

Torrez, who worked briefly in the internet sector after graduating from Harvard and before earning a master’s degree from the London School of Economics, has long embraced technology as a crime-fighting tool.

“In the DA’s office, we built one of the first platforms that integrates information and data from a variety of otherwise fractured information systems, then synthesized it so that police and prosecutors have a holistic view of criminal activity, including geographic trends and high-impact offenders,” he says. “We were also the first office in the state to use forensic genealogy to solve cold-case sexual assault and other violent crimes.” He is now focused on expanding similar data-driven tools in the attorney general’s office.

Torrez describes his approach as a prosecutor and lawyer as “balanced.” “Like so many things in this country, we like to polarize. So, you are either a ‘tough on crime’ prosecutor and want to lock everyone up or you believe ‘anyone can be rehabilitated’ even the most violent offenders. The reality is that being a responsible prosecutor requires balance. Sometimes you have to be the reformer in a room full of prosecutors and other times you have to be the prosecutor in a room full of reformers.”

As attorney general, he enjoys channeling his legal experience into new areas—such as how to resolve a dispute over feral cattle in southern New Mexico between the State Livestock Board and the U.S. Forest Service. Torrez was called to act when members of the Livestock Board said they planned to arrest federal agents over their proposal to shoot the cattle from helicopters.

“That was a first, having to tell a local agency that, no, they could not arrest members of the federal government. I definitely didn’t encounter a hypothetical like that at Stanford,” he says with a laugh. SL