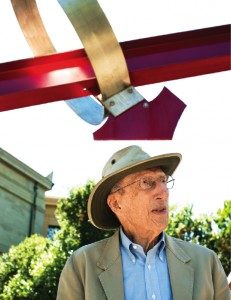

Renaissance Merryman

It isn’t difficult to imagine John Henry Merryman, the Nelson Bowman Sweitzer and Marie B. Sweitzer Professor of Law, Emeritus, and affiliated professor emeritus in the Department of Art, as a gentlemanly inhabitant of an earlier era, steadfastly pursuing the Renaissance ideal. Many of us have seen him striding across campus leading a tour of Stanford’s famed sculptures, smiling as he describes not only the art but the story behind its acquisition. He is scientist, musician, teacher, scholar, and art connoisseur rolled into one—a chemist who became an internationally acclaimed comparative law scholar and who established the field of art law.

But his path to the law was not a straight one, and there were a few unexpected turns along the way.

Born in Portland, Oregon, in 1920 and raised in the midst of the Great Depression, Merryman initially aspired merely to earn a living. He was a very good student, but with no one subject outstanding. He decided to apply to college to study chemistry, because, as he says, “I heard that if you were a chemist, you’d find a job, and that’s why I decided to become one.”

But Merryman needed money to pay for his education. He had started playing piano, classical and popular, in high school and had formed a dance band—John Merryman and His Merry Men—which led to his becoming a professional, card-carrying musician.

This, in turn, allowed him to strike a deal with the University of Portland: “The school would admit me and every time I played a job, I would give it half of what I got paid,” he says. And in this way he was able to finance his bachelor’s degree in chemistry, which he received in 1943. But after receiving his MS in chemistry from the University of Notre Dame and while in the midst of working on his PhD at the University of Chicago, he had a revelation. “I realized that I didn’t have the kind of dedication to life in the laboratory that being a chemist required,” he says.

Attracted by the idea that lawyers dealt with real life and real problems, and by the glamour of civil liberties and social justice issues, Merryman returned to Notre Dame to study law, which he accomplished while also teaching chemistry and math full time to pay for his legal education. Merryman loved law school and was surprised by how easy it was compared with studying chemistry.

He also greatly enjoyed teaching and writing, and it was during this time that he began to aspire to a career in legal scholarship. Following his graduation from Notre Dame in 1947, NYU School of Law provided him with a teaching fellowship and the opportunity to continue his legal studies and he received his LLM in 1951. He then entered the teaching market and accepted an offer from the University of Santa Clara. He had never been to California and was struck by both the state’s natural beauty and the attractive campus—quickly making it his home.

During his five years at Santa Clara, Merryman taught courses in personal property, titles, estates, conveyances, landlord and tenant, and future interests, while publishing extensively and playing piano engagements, sometimes six nights a week. And then something unexpected happened: He was fired.

According to his contract, Merryman was prohibited from doing anything contrary to Catholic doctrine and morals. By marrying Nancy Edwards (BA ’70), a divorced woman, he had violated this provision. The letter announcing the university president’s decision arrived just three days after the wedding ceremony. But if not for this upheaval, he might never have come to Stanford Law School. Santa Clara Law’s dean was outraged by the university’s action and implored Stanford Law School Dean Carl Spaeth to give Merryman a job, which he did.

And so in 1953, Merryman began a two-year appointment working with Stanford’s legal writing program. While not yet a full member of the faculty, he was delighted to be at Stanford and made many friends, especially among the younger faculty members. He also found time to complete both his first really important scholarly article, “The Authority of Authority: What the California Supreme Court Cited in 1950,” published by the Stanford Law Review in 1954, and his JSD, which was awarded by NYU School of Law in 1955.

A s his two-year appointment was coming to an end, Merryman’s friends on the faculty tried to find a way to keep him at Stanford. The law librarian had just left and they persuaded Spaeth to offer him a job as half-time law librarian and half-time property teacher.

Merryman’s tenure as law librarian marked the beginning of the library’s transformation from a rather modest operation to the premier facility it is today. With no library experience, except as an avid user, he created his own classification system that was considered ingenious at the time and that led to his publication of an article and two books on library science.

And then in 1960 Spaeth invited Merryman to join the faculty as a comparative law specialist. Having searched extensively for the right candidate, Spaeth and the faculty decided that the law school should grow its own comparative law professor—specifically, Merryman.

Merryman had no relevant experience other than visiting Europe as a tourist and having an interest in language, but he jumped at the offer. The field was wide-open and this was an opportunity to carve out his scholarly niche.

Spaeth agreed that Merryman could concentrate on the Italian legal system and sent him to Italy for a year. There, Merryman studied, taught, and established his credentials as a serious comparative law scholar, publishing several articles and books on the Italian legal system. He went on to become internationally renowned in the field, serving as a visiting professor worldwide, receiving honorary doctorates from universities in Aix-en-Provence, Trieste, and Rome, and even earning the Italian Order of Merit.

Meanwhile, the law school was undergoing a number of changes. The infamous raid on Columbia Law School netted a number of prominent new faculty members, and a new dean, Bayless Manning, took charge in 1964. It was Manning who persuaded Merryman to write his most successful and popular book, The Civil Law Tradition: An Introduction to the Legal Systems of Western Europe and Latin America, now in its third edition. And it was Manning who presided over Merryman’s receipt of tenure.

Manning also appointed Merryman to be chair of the building committee, which guided construction of the law school’s current home. Because of Merryman’s involvement with the art world (by this time, his wife had become a successful international art dealer), he was tasked with making many of the aesthetic decisions. Merryman’s interest in art also led to a friendship with his campus neighbor and Stanford art professor, Albert Elsen. Over lunch at the Faculty Club one day in 1970, the two decided to teach a course on art and the law.

Thus began one of the most illustrious chapters of Merryman’s career. He quite literally wrote a casebook on art law (with Elsen)—Law, Ethics and the Visual Arts. Now in its fifth edition, the book established this important field of legal scholarship. In 1971, Merryman and Elsen developed and taught the very first Art and the Law class at Stanford Law or any law school, introducing students to the intricacies of this new field.

Merryman also was active in forming the ABA’s Visual Arts Division, serving as its first chairman, and he founded the International Journal of Cultural Property, serving as chairman of its editorial board for several years. He has published prolifically on issues ranging from whether the Elgin Marbles should be returned (“No”), to the nature of “cultural property,” to the moral rights of artists to prevent damage to their artwork. In service to the wider university, he has also been president of the Faculty Club and chairman of the Faculty Senate.

Despite officially retiring in 1986, Merryman continues to work at a fast pace. He still teaches Art and the Law and can be found on most mornings in his law school office, busily engaged in his latest scholarly venture.

But Merryman’s interest in art is not just academic. He also was responsible, again with Elsen, for the acquisition of outdoor sculptures throughout the Stanford campus. One of these sculptures, which stands outside the Cantor Center for the Visual Arts, is his particular favorite, The Sieve of Eratosthenes, by Mark di Suvero. It was acquired (with a donation from Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro) and dedicated in honor of his 80th birthday. Merryman was (and continues to be) overwhelmed by the gift, which he describes as the highlight of his career. “Here’s a great work of art by a great artist and it has my name on it. Is there a greater honor?”

2 Responses to “Renaissance Merryman”

Comments are closed.

Susan McFadden

I greatly enjoyed the article on Professor Emeritus John Henry Merryman. Having graduated in 1980 I benefitted from his tutelage each of my three years at the Law School. In my first year I took his classes in Property and in Legal Systems of Western Europe and Latin America. In the second year he oversaw my semester abroad at Hamburg’s Max Planck Institut für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht, and then in my third year he supervised my independent study and shepherded to publication the resulting paper.

In addition to being a world-renowned scholar, Professor Merryman is a gentle and thoughtful person—a real Mensch. Some of this came through in your lovely article, which was good to see. For me, he was an oasis of kindness in the often difficult law school environment.

James Wang

Great article. Enjoyed it very much.