S-Term Field Study on Ukraine

We studied millennia of Ukrainian history. We debated the legality of seizing frozen Russian assets to finance Ukraine’s postwar reconstruction. And we drank a cherry liqueur that was once a staple in every household of Old Lviv.

As Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine dragged into its twentieth month this September, we took off with a group of Stanford Law peers from campus to Warsaw, Poland, as part of the school’s inaugural S-Term program (S stands for September). Led by Erik Jensen, director of Stanford’s Rule of Law Program, and Michael Strauss, JD ’01, general counsel at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, our S-Term class, titled Ukraine: The Promise and Perils of Legal Reform and Governance, in Wartime and Reconstruction, was the first-ever course at the law school to focus on Ukraine. Inspired by S-Term’s vision of providing unique, immersive learning experiences with faculty leaders and renowned practitioners, Professors Jensen and Strauss gave students an opportunity not only to learn about but also to help address the many challenges facing Ukrainians as they seek a secure, prosperous, and democratic future.

In the first half of the course, we shared conversations on Stanford’s campus with experts ranging from former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Bill Taylor to Professor Francis Fukuyama of Stanford’s Freeman Spogli Institute, Judge Abraham Sofaer of the Hoover Institution, and Yuliya Ilchuk, associate professor of Slavic languages and literatures. We then traveled 6,000 miles closer to Ukraine’s front lines for the course’s latter half. Only 160 miles away from Ukraine in our conference room at the Warsaw offices of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, we were close enough for Ukrainian leaders to make the trip across the border to meet with us. To our great honor, many did.

On our first day in Warsaw, we were joined at the office by Ukraine Parliament member Oleksandra Ustinova, a 2019 visiting scholar in Stanford’s Ukrainian Emerging Leaders Program at the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law. She was joined in conversation by former U.S. Ambassador to NATO Kurt Volker. Later in the week, Judge Olena Kibenko of Ukraine’s Supreme Court made the train journey from Kyiv to Warsaw, along with Judge Kateryna Shyroka of Ukraine’s High Anti-Corruption Court and a senior detective from the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine. Each day brought fascinating new speakers.

Through these discussions, we learned that Ukraine is fighting what might be described as a three-front war. The most obvious and existential front is playing out on the battlefield. Yet even as it fights to repel foreign invaders, Kyiv has not ceased prosecuting its war against domestic corruption. To secure its future in the European Union and in NATO, Ukraine continues to implement transparency, democratization, and good governance reforms. On the third “front,” Ukraine is planning for the postwar reconstruction of its land, economy, and judiciary.

In many ways, progress on one front reinforces progress on the others. For example, fielding an effective army made all the more urgent Ukraine’s prewar efforts to prevent and punish the corruption that historically undermined defense expenditures. The invasion has likewise accelerated other prewar reform priorities. Introduced but underutilized before the war, Ukrainian e-government services now provide millions of Ukrainians with access to social services, from documentation and pensions to business loans, even while being displaced abroad. These online services are enabling young Ukrainians to create tech startups Kyiv considers critical to its postwar economic recovery and development.

As we pondered the challenges of rebuilding Ukraine after its bombardment by Russia, we had a model before us in the city of Warsaw. Looking out the window of our conference room on the upper floor of a sleek skyscraper, we saw the bustle of a booming city where once war had left only rubble in its wake. Warsaw’s nickname, the Phoenix City, reflects the fact that about 85% of its prewar structures were destroyed during the Nazis’ quest to quash the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. As we toured the Old Town of Warsaw, a UNESCO World Heritage site painstakingly reconstructed to resemble its prewar appearance, we were inspired to see that no amount of physical destruction could permanently destroy a proud nation and its capacity for renewal. With the support of allies, Ukrainian cities can also be liberated and rise from the rubble like phoenixes.

Detective Oleksii Geiko of Ukraine’s National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) Photo by Michal Gonet

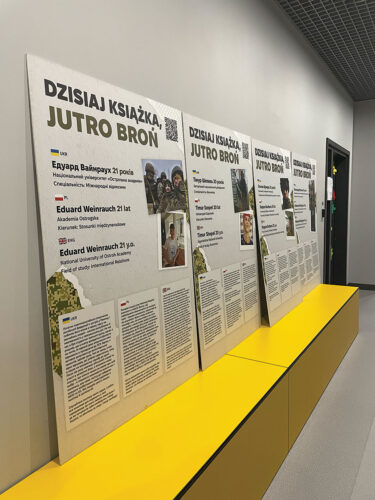

We were impressed to see Warsaw leading by example in another regard: supporting the over one million Ukrainian refugees living in Poland. In perhaps the most poignant moment of our trip, students at the University of Warsaw explained how they organized an impressive campaign to provide refugees with support ranging from housing and job procurement to language training and recreational opportunities. Many of the volunteers were themselves Ukrainian refugees. Hearing their stories about the lives they left behind, their families remaining on the front lines, and their hopes of reuniting again stirred us.

We left Warsaw with a better understanding of Ukraine’s challenges. We also left determined to play a role in helping Ukrainians face those challenges by advocating for continued material aid from Congress and by devising mechanisms to adjudicate claims for war damages. Arriving back on campus, inspired by the courage of the Ukrainian people, we’d say the goal of S-Term was accomplished. Reading about international law and the rule of law in the classroom can sometimes seem abstract, even divorced from our present reality. But having heard from the victims of Russian aggression and the beneficiaries of Ukraine’s rule-of-law reforms, we have no doubt that well-ordered and consistently observed laws affect lives in ways that often go underappreciated. After this course, we won’t forget this. SL