Using AI to Map Racial Covenants

RegLab Team Develops Tool to Identify Property Deed Racial Covenants to Comply with Law

When Daniel E. Ho purchased a home in Palo Alto, he got more than he bargained for. Buried in the reams of papers he had to sign at closing was an unsettling relic of the past—one that ignited a spark for new research.

“We had to sign papers saying that the ‘property shall not be used or occupied by any person of African, Japanese or Chinese or any Mongolian descent,’ except for the capacity of a servant to a White person,” says Ho, the William Benjamin Scott and Luna M. Scott Professor of Law, director of RegLab, and senior fellow at Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, or HAI.

“It was a stunning testament to housing discrimination in the area, and it’s been constitutionally unenforceable since 1948,” says Ho.

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court holding such clauses unenforceable, racially restrictive covenants still litter deed records across the U.S. In 2021, California enacted a law that requires the state’s 58 counties to create programs to identify and redact deed records that include racial covenants.

But the new law also poses a daunting task: Santa Clara County alone has 24 million deed documents, totaling 84 million pages, dating back to 1850. “Prior to this collaboration, our team manually read close to 100,000 pages over weeks to identify racial covenants,” Assistant County Clerk-Recorder Louis Chiaramonte says, “and it was a challenging undertaking.”

To comply with the law, some California counties contracted with commercial vendors. Los Angeles County, for example, hired a company for $8 million to conduct this scan over seven years. In other jurisdictions, teams of citizens have valiantly crowdsourced these efforts with thousands of volunteers poring over deed records. But not all jurisdictions have such resources.

The County of Santa Clara, home to Silicon Valley, approached it differently. Stanford University’s Regulation, Evaluation, and Governance Lab (RegLab) partnered with the county to use the power of AI—and large language models, specifically—to assist in this monumental task.

“The County of Santa Clara has been proactively going through millions of documents to remove discriminatory language from property records,” says Chief Operating Officer Greta Hansen. “We’re grateful for our partnership with Stanford, which has helped the county substantially expedite this process, saving taxpayer dollars and staff time.”

Shining a Light on 5.2 Million Deeds

The team, led by Stanford’s RegLab and including HAI affiliates and Princeton Professor Peter Henderson, JD/PhD ’23, curated a collection of racial covenants from various jurisdictions in the country and trained a state-of-the-art open language model to detect racial covenants, with almost perfect accuracy.

“We estimate that this system will save 86,500 person hours and cost less than 2 percent of what comparable proprietary models would have,” says co-lead author Faiz Surani, a fellow with the RegLab. The team zoomed in on 5.2 million deed records between 1902 and 1980, the period most at issue.

“We believe this is a compelling illustration of an academic-government collaboration to make this kind of legislative mandate much easier to achieve and to shine a light on historical patterns of housing discrimination,” says co-lead author Mirac Suzgun, JD ’26 (PhD ’27), a computer science student. Chiaramonte agreed: “This collaboration paved a new path for how we can use technology to achieve the momentous mandate to identify, map, and redact racial covenants. It reduced the amount of time our team needed to review historical documents, dramatically.”

The team has released the paper at https://reglab.github.io/racialcovenants/ and is making the model available to enable all jurisdictions faced with this task to identify, redact, and develop historical registers of racial covenants more effectively. SL

History as a Guide

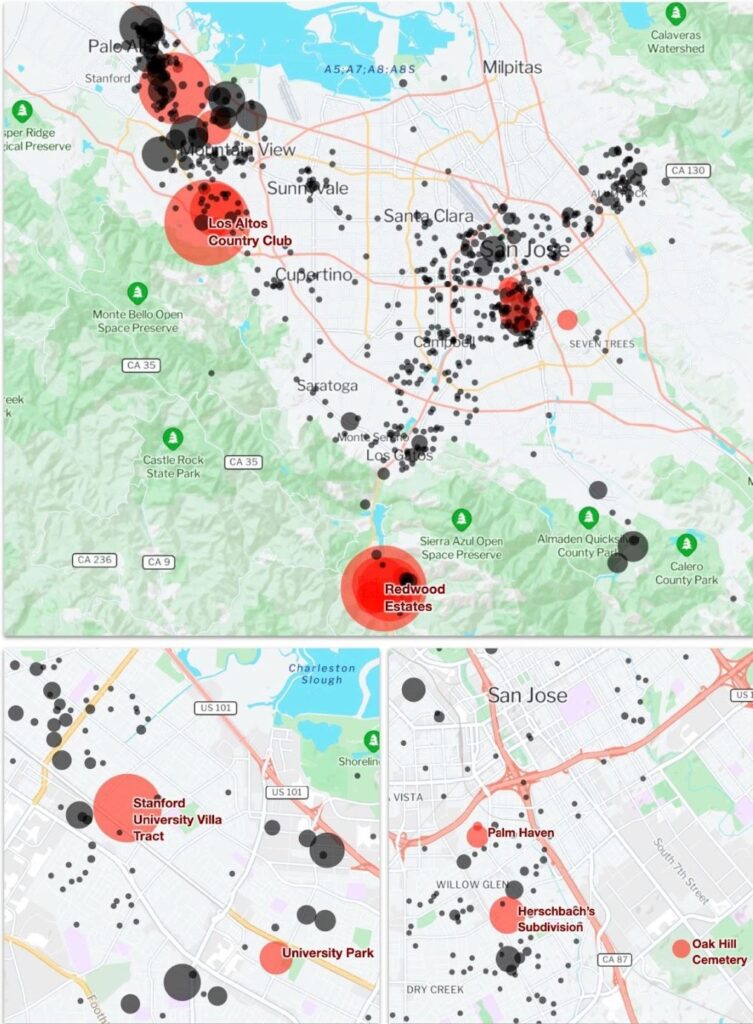

The team cross-referenced historical maps to locate properties with racial covenants. They matched textual descriptions of maps (e.g., “Map [that] was recorded . . . June 6, 1896, in Book ‘I’ of Maps at page 25”) to administrative records in the Santa Clara County Surveyor’s Office to geolocate tracts. These maps revealed extraordinary insights into the evolution and diffusion of racial covenants in Santa Clara County:

1) The team estimated that one in four properties in Santa Clara County was subject to racial covenants as of 1950.

2) Only 10 developers were responsible for a third of the identified covenants, suggesting that developers had a lot of say in how Santa Clara County was constructed.

3) Racial covenants excluded African Americans at the same rate as Asian Americans, even when African American residents were less than a tenth the size of the Asian American population.

4) The team found a striking instance of a San Jose-owned cemetery that included burial deeds only for “Caucasians.” This goes against the conventional historical account that racial covenants were used only between private parties after the U.S. Supreme Court banned state-based racial zoning.