The Drug War at 100

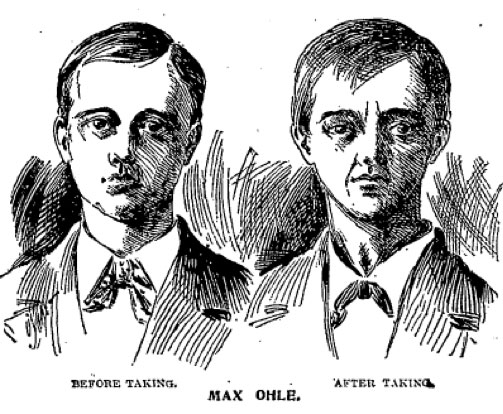

These portraits of Max Ohle in the Chicago Tribune, before and after he became a “slave to cocaine,” may have prompted the state to ban cocaine.

One hundred years ago this week President Woodrow Wilson signed the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 and committed the federal government to combating the domestic drug trade. If any single event launched our modern drug war, this was it.

The Harrison Act aimed to ban nonmedical use of opiates and cocaine. Together with the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, it federalized what till then had been a state-by-state skirmish against recreational drugs. Important as they were, these federal laws arrived too late to teach us why anti-drug laws took rise. The Harrison Act became law only after thirty-five states and territories had banned opium and forty-six had banned cocaine. Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act only after all fifty states and territories had banned marijuana.

So the story of America’s drug war unfolded first at the state and local levels. Though the plotline varied from state to state and drug to drug, one theme emerges again and again. That theme ties the earliest antidrug laws to issues of race and power, but not in ways commonly alleged. It’s often said these laws grew out of hatred of groups the public linked with each drug—the Chinese with opium, African-Americans with cocaine, Mexicans with marijuana. Yet there’s hardly a hint of this simple racist plotline in the histories of the earliest state and local antidrug laws.

Instead a different racial theme emerges, beginning with what seems to be America’s first law banning any non-alcoholic drug—San Francisco’s 1875 ordinance against opium dens. That law made it a misdemeanor to keep or visit any place where opium was smoked. The San Francisco Chronicle explained that the Board of Supervisors had acted after learning of “opium-smoking establishments kept by Chinese, for the exclusive use of white men and women“—and of “young men and women of respectable parentage” going there.

The block-face reference to white men and women spotlights the supervisors’ concern: that their children and those of their friends and constituents could lie stoned in a fetid den. Indeed enforcement of early anti-dens laws fell mainly on dens catering to whites. In San Francisco and other Western towns, police often overlooked Chinese opium dens selling only to the Chinese. “All we can do,” said San Francisco Police Chief Phillip Crowley, is “keep them from opening places where whites might resort to smoke.”

The focus on dens serving whites misled even the New York Times. In 1876 the Times said San Francisco’s ordinance had made it an offense “for the keeper of any opium den to allow a white person to smoke in the place.” In truth the law said “No person” shall keep or visit an opium den. Though race-neutral on its face, the law was enforced unevenly against white smokers and those who sold to them, whether Chinese or white. In Idaho, with the nation’s largest proportion of Chinese residents, the law was more frank. An 1887 statute punished “Every white person” who kept an opium den and “Every white person” who used opium there—and no one else.

Nor did fears of racial mixing drive these early laws against opium dens. It’s true lawmakers worried young white women could lose their virtue while sunk in an opium haze. Dr. Harry Hubbell Kane, perhaps the day’s leading opium expert, said lawmakers reacted to reports that “male smokers (Americans) . . . were continually beguiling women and young girls to try the pipe, and effected their ruin when they were under its influence.”

Kane’s parenthetical “(Americans)” made clear it was white men—not Chinese—who threatened white women’s virtue. Not until 1883 did reports of racial mixing in opium dens emerge in any number. Those reports appeared not in the West, where anti-dens laws had been in force for years, but in Manhattan, where an ethnic rivalry led to a cruel hoax and a slur against the Chinese.

Trouble brewed as the city’s Chinatown encroached on the Catholic Church of the Transfiguration. Irish members of the church’s Catholic Young Men’s Association, led by the assistant pastor, alleged that “many girls who live in this neighborhood have been ruined by these Chinamen. Children as young as 11 and 12 years have been led . . . into the opium dens, where they are induced to stupefy themselves with opium.”

Though the Times branded the charges “preposterous,” the story electrified the city’s tabloid press and whipped across the nation. Before the hoax was revealed barely a week later, the story had dug into the public imagination and left a trail of copycat reports.

Similar distortions have muddied the histories of the earliest laws against cocaine and cannabis. Those laws also responded to concerns of drugs corrupting whites and especially white youth. Then, years later, the press veered toward sensationalized accounts of nonwhite users crazed by coke and locoweed.

Consider cocaine, which arrived on American shores in 1884 as an Austro-German pharmaceutical. Newspapers marveled at the new wonder drug, which permitted painless eye surgeries on conscious patients. Soon came a trickle—then a stream—of reports of doctors and pharmacists hooked on cocaine. Because the drug was pricey and available mainly through medical channels, virtually every (and perhaps every) news story about recreational abuse for the next many years concerned whites.

So when states started banning cocaine, they did so against a record of abuse seemingly always involving whites. And as users got their coke from doctors and pharmacists, the suppliers too were white. The geographic scatter of the first five states to ban cocaine—Oregon in 1887, Montana in 1889, Colorado and Illinois in 1897, Massachusetts in 1898—belies any simple claim that racial animus gave rise to these laws.

Instead these laws seem to trace to a concern to that whites and especially white youth were falling victim to cocaine. In Chicago fourteen-year-old Max Ohle became a poster child of this brewing cocaine epidemic. A North Side barber’s son and pharmacist’s errand boy, Max had dabbled in his boss’s cocaine-laced cold remedies. Now he was a “Slave to Cocaine,” the Chicago Tribune declared in a page-one headline. The Tribune printed portraits of young Max “before taking” and “after taking” cocaine, showing a handsome lad turned haggard. His story was likely on legislators’ minds the next March, when a Chicago assemblyman introduced a successful bill to ban cocaine.

Later the cocaine addicts featured in the press were increasingly nonwhite. In February 1914, as the Harrison Act wended through Congress, the New York Times Magazine ran the notorious banner, “Negro Cocaine ‘Fiends’ Are a New Southern Menace,” over an account of cocaine-crazed killers insensible to lawmen’s bullets. Like the rumor campaign targeting New York’s Chinese community, this article distorted the views of later historians, who have assumed similar fears prompted earlier anticocaine laws.

So too with the earliest laws against cannabis, many of which took form against a background of press accounts that rarely mentioned Mexicans except when reporting on the Mexican Revolution and rarely mentioned marijuana at all. Again the scatter of the earliest states to ban cannabis—Massachusetts in 1911 and Wyoming, Indiana, Maine, and California in 1913—forecloses any simple story about race.

In New England, which unexpectedly led the nation in banning cannabis, the critical force was the New England Watch and Ward Society, a group committed to “removal, by both moral and legal means, of those agencies which corrupt the morals of youth.” The society both wrote and promoted anticannabis laws in Massachusetts and Maine and played an important role in adoption of anticannabis laws in Vermont in 1915 and perhaps Rhode Island in 1918. Largely as a result of the Watch and Ward’s efforts, four of the first ten states to ban cannabis lay in New England. Yet if census figures may be trusted, the population of Mexican-Americans in the entire six-state region was about 65.

Even further west in Indiana and Wyoming and California, there’s little evidence early anticannabis laws responded to concerns about Mexicans using or selling marijuana. In later years, however, news stories increasingly linked Mexicans with the drug and alleged marijuana-induced violence. A 1918 report in the Los Angeles Times headlined, “Crazed Mexican Runs Amuck and Creates Reign of Terror in Plaza District,” offers a telling example.

Hence from drug to drug a pattern repeated itself. The earliest anti-drug laws sought to protect whites’ morals and aimed no spite at other groups. In time, however, racial hatred infected enforcement of these laws and colored depictions of their violators.

Today there’s a certain historical irony at work, as laws permitting recreational marijuana take hold. The racial skewing of anti-drug law enforcement over the last several decades has prompted cries to liberalize our drug laws. So laws that rose up without racial roots now may topple because of their enforcement with an uneven hand.

George Fisher is a professor at Stanford Law School and author of a forthcoming book on the history of alcohol and drug regulation.

2 Responses to “The Drug War at 100”

Comments are closed.

Post Pagination

James Luce

Dear Professor Fisher,

Thank you for the enjoyable romp through a tangled briar patch of our history. Of course, the fact that the motivation of anti-drug laws was to protect white people is an indication of a racist root if not a a racial root. Obviously the Great White Legislators viewed non-whites as not quite human, not in need of protection. And another irony is exposed…that it was the medical profession that introduced White America to cocaine. Similarly, for decades we were told that “8 out of 10 Doctors agree that Camels are the best (substitute whatever cigarette brand, but the ads were the same). Finally, there can be no doubt that the War on Drugs has been an economic, social, and foreign policy disaster. Looking forward to the release of your book.

Orlando La Rosa

The only logical reason for there to still be, in this day and age, a Federal law against Marijuana is because the alcohol, tobacco, cotton and drug companies are flooding Washington with money to keep it illegal. Their claim is that they’ll lose money if Marijuana is legalized. How can someone lose money they have yet to get? Anyway, stop the flow of money and Marijuana will be legalized. Granted, I have no proof of this actually going on, but I would be willing to bet some money that it’s true. There’s no other reason for Marijuana to be illegal.