Can Police Officers Be Held Criminally Responsible for Using Chokeholds?

The Stanford Center for Racial Justice has begun publishing chapters of our Model Use of Force Policy in beta release. The Model Policy is intended to contribute to the long line of efforts to improve and reform policing and promote practices that will be fair, safe, and equitable for everyone. This essay continues our staff series examining how use of force policies intersect with legal proceedings in a variety of situations. Read Chapter 4 of the Model Policy—Chokeholds and Breathing Impairments—here.

On Sunday, May 14, 2017, a man named Tashii Farmer approached officers in a hotel cafe on the Las Vegas Strip. Farmer had a brief conversation with the officers, asking where he could find the nearest water fountain. Officers asked Farmer why he was sweating and Farmer responded that he was being chased. Although unclear why, Farmer began running away from the officers.

The officers began to pursue Farmer on foot. One officer, Kenneth Lopera, continued pursuing Farmer through a hotel stairwell and then onto the Las Vegas Strip. When he began to catch up to Farmer, Lopera claims that Farmer was attempting to open the tailgate and then the driver-side door of a white truck. However, in a post-incident report, the driver of the truck stated he did not believe Farmer was attempting to open the door or tailgate.

When Lopera caught up to Farmer, Lopera discharged his taser, causing Farmer to fall on his back to the ground. Lopera used verbal commands to tell Farmer to roll onto his stomach. Farmer raised his hands and said, “I will.” Lopera again discharged his taser. Lopera discharged his taser on Farmer for a total of seven times.

Hotel security caught up to the incident and attempted to help Lopera by restraining Farmer. While Farmer attempted to pull the taser prongs from his back, Lopera then holstered his taser and began striking Farmer with his hand against Farmer’s face and head. After shouting several more verbal commands to “get on your stomach,” Lopera wrapped his arms around Farmer’s neck applying what Lopera called a “rear naked chokehold.” Lopera held the hold for one minute and twelve seconds until Farmer went unconscious. He held this hold despite his supervisor recommending he cease the hold. Farmer never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead at the hospital.

After his death, Farmer’s mother, Trinita Farmer, filed a civil lawsuit against officers involved in the incident related to her son’s death and against the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department (LVMPD). The LVMPD settled with Ms. Farmer for $2.2 million. In their settlement, presumably because of Lopera’s actions, the LVMPD admitted that “Farmer[’s death] rose to the criminal level.”

Below, we discuss how federal criminal law might apply to Lopera’s actions and whether law enforcement agencies’ use of force policies have an influence on officers’ exposure to such charges.

How do federal prosecutors hold police officers accountable?

Federal prosecutors play a different role than local district attorneys. Local district attorneys can bring charges against officers under state criminal law passed by state legislatures. On the other hand, when holding officers accountable for excessive force, federal prosecutors usually must bring claims under a federal statute passed by the U.S. Congress—18 U.S.C. § 242—for criminal use of excessive force. This statute originated in the Reconstruction era, and was designed to deter white supremacist organizations that were threatening and lynching formerly enslaved African Americans. The statute prohibits anyone acting under color of any law from depriving an individual of their constitutional rights. Under the statute, government actors (like police officers) may face prison-time or monetary penalties for violating someone’s constitutional rights while acting with governmental authority. Therefore, police officers like Lopera, face the possibility of federal prosecutors bringing criminal charges under this statute for their alleged use of excessive force.

How frequently do federal prosecutors bring excessive force claims?

Although federal prosecutors can bring charges for excessive force against local officers, federal prosecutors rarely do so. For instance, in 2019, federal prosecutors brought 49 federal criminal deprivation of rights claims against officers out of more than 184,000 federal criminal prosecutions. This happened despite officers killing nearly 1,000 people while using their badge and countless other non-lethal excessive force incidents. Scholars attribute the infrequency with which federal prosecutors charge officers to the “blue wall of silence”—a refusal by officers to testify against their fellow officers—and the difficulty prosecutors face when proving a federal claim of excessive force.

What must prosecutors prove when bringing federal criminal claims of excessive force?

Two questions become relevant to prosecutors when attempting to prove the officer acted with criminal excessive force. First, much like a federal civil claim for excessive force, prosecutors must prove that the officer acted unreasonably, which violates the Fourth Amendment. Second, prosecutors must prove that the officer acted willfully when the officer acted unreasonably.

Is criminal reasonableness the same as civil reasonableness?

The first question, requiring prosecutors to prove the officer acted unreasonably, is guided by the same elusive standard that defines reasonableness in civil claims of excessive force—Graham v. Connor’s “objective reasonableness” standard, which we discussed in our last essay.

Although courts largely do not take into consideration use of force policies when determining whether an officer’s actions were civilly reasonable, one might expect the opposite in the case of criminal excessive force. That is, one might expect that an officer’s violation of department policy factors heavily into evaluating whether the officer committed a crime.

However, federal courts view Graham and its “objective reasonableness” standard as sacrosanct in determining whether an officer acted reasonably—meaning, courts will not find an officer acted unreasonably merely because the officer violated an agency’s use of force policy. Rather, the “objective reasonableness” standard requires courts to consider “allowance for the fact that police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments—in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving.”

Consequently, courts may sometimes allow a use of force policy into evidence, but the policy alone will not determine whether the officer acted reasonably.

In a hypothetical federal criminal action against Lopera, his violations of LVMPD’s neck restraint and taser policies may have informed a jury on the question of whether Lopera acted unreasonably. However, the violations of policy alone would not definitively determine Lopera’s guilt on the federal criminal excessive force charges.

What is willfulness?

The second question in the federal criminal excessive force context is whether the officer acted willfully. Essentially, the prosecutor must prove that the officer wanted to use excessive force—or as the Supreme Court describes it, the officer acted “in open defiance of a constitutional requirement which has been made specific or definite.” The willfulness standard requires prosecutors to prove that officers knew the force they used against the individual was excessive and the officer desired to use this excessive force.

But, excessive force, as discussed above, is determined by what is reasonable. And courts are not entirely clear on what constitutes reasonable officer conduct—making it difficult for prosecutors to show that an officer knew they were acting “in open defiance of a constitutional requirement which has been made specific or definite.” Although the Supreme Court has explained that “willfulness may be inferred from blatantly wrongful conduct,” the Court has also asserted that an officer’s mistake, fear, misperception, or even poor judgment does not constitute willful conduct.

So, how exactly can a prosecutor show evidence that the officer knew that force was excessive? The Brennan Center describes it as prosecutors having to “peer into [the officer’s] mind” to show juries how to evaluate whether the officer acted willfully. Scholars argue that the willfulness standard is unclear and “difficult to demonstrate even in cases of clear police misconduct.” Prosecutors have sometimes decided against bringing criminal charges against an officer because of the stringent standard.

Had federal prosecutors brought charges against Lopera, they would have had to prove he acted willfully in depriving Farmer of his constitutional rights. The jury would have had to “peer into [Lopera’s] mind” to determine if he knew whether the neck restraint was excessive and acted to apply this excessive force. Could the prosecutor have introduced evidence of the LVMPD use of force policy to show Lopera knew a neck restraint was excessive?

A use of force policy might help prove exactly whether officers, like Lopera, knew their force was excessive by helping juries understand the officer’s knowledge and potential state of mind. The policy might show that the officer knew that certain conduct was reasonable and other conduct was excessive. At least one court affirms the ability of use of force policies to “peer into [the officer’s] mind” and suggests that when an officer displays actions inconsistent with their departmental training, one can infer that the officer intended to use excessive force.

However, because of the Graham “objective reasonableness” standard, officers operate with the understanding that if another “reasonable officer on the scene” would engage in such conduct, then their actions are not excessive—and therefore the officer might argue that they were not willfully engaging in excessive force. Although, as mentioned above, courts sometimes utilize use of force policies to inform the question of whether officers acted reasonably, proof of a policy violation alone will likely not be sufficient to demonstrate an officer’s willfulness.

Did Lopera violate provisions under the Model Policy?

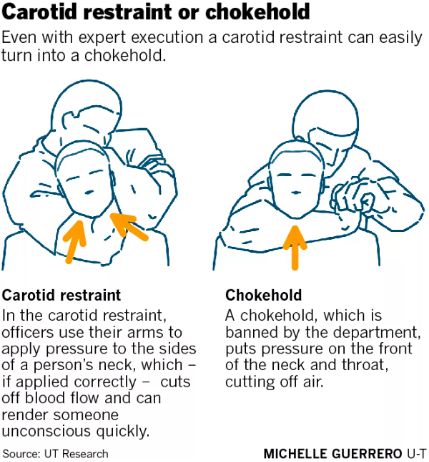

The SCRJ Model Policy* (“Model Policy”) defines chokeholds as “lethal hands-on maneuvers that may cut off the supply of blood and oxygen to the brain” and includes under this definition strangleholds, neck restraints, and carotid restraints. Any and all chokeholds are prohibited under the policy. In the Chokeholds chapter, the Model Policy also outlines directives and prohibitions on breathing impairments. Breathing impairments include strikes to the neck and positional asphyxia—the face-down position most notoriously used by Officer Derek Chauvin against George Floyd.

For this essay, our focus is on Lopera’s use of a “rear naked chokehold.” As mentioned above, under the Model Policy, chokeholds are “lethal hands-on maneuvers” that are “inherently dangerous to human life.” Lopera used the chokehold on Farmer after several attempts at restraining Farmer failed. The LVMPD later stated that Farmer would not have been charged with a crime. Lopera also did not see Farmer commit a crime. Other than the contested issue of whether Farmer attempted to open the door of the white truck, Lopera had no knowledge that Farmer was a threat to the public. This suggests that Lopera used a “lethal hands-on maneuver” against an individual who had not committed a crime. Lopera’s “rear naked chokehold” blocked the blood in Farmer’s carotid arteries. The Model Policy prohibits the restraint Lopera administered on Farmer.

Why didn’t Officer Lopera get convicted of a crime?

One can only speculate why Lopera was not convicted of a crime. Local prosecutors initially charged Lopera with involuntary manslaughter and “oppression under color of office.” The local prosecutors formed a grand jury to decide whether to indict Lopera, however, the grand jury decided against indicting him. Federal prosecutors also decided not to indict Lopera.

One could attribute the lack of indictment to the difficulty in proving a police officer used excessive force. As mentioned above, the willfulness standard is a high bar for federal prosecutors to overcome. Additionally, prosecutors and the grand jury may have been deterred by uncertainty about the cause of Farmer’s death. The Clark County coroner ruled Farmer’s death a homicide due to asphyxiation from police restraint procedures, but contributing factors included methamphetamine intoxication and an enlarged heart. Prosecutors and the grand jury may have been dissuaded to charge Lopera because they could not definitively link the cause of death with the chokehold. Regardless, the LVMPD stated Farmer committed no crime. Lopera, on the other hand, repeatedly violated de-escalation and taser policies and used a restraint unapproved by the LVMPD.

Why are chokehold policies important?

The Model Policy prohibits, under any circumstance, chokeholds administered by police against individuals. The outright prohibition follows police departments across the nation who have also banned chokeholds, including New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Houston. Still, many police departments do not have adequate chokehold policies, which can lead to tragedies like those of Tashii Farmer, Eric Garner, George Floyd, James Thompson, Allen Simpson, Rodney Lynch, Dustin Boone, and countless others.

In addition to the inherent danger of blocking air and blood supply to the brain, the Model Policy prohibits chokeholds because of its necessity to require a high degree of skill and training to use properly—especially when someone is moving and struggling. For instance, if an officer places their arm in the wrong place while administering a chokehold, the officer risks subjecting the individual to serious injury or death.

Prior to Farmer’s death, the LVMPD allowed police to use neck restraints on anyone who was not complying with officer commands. After Farmer’s death, the LVMPD stated the approved neck restraint was different from the unapproved “rear naked chokehold” used by Lopera. Additionally, after Farmer’s death, the LVMPD updated its policy to classify neck restraints as deadly force and only allow them when an individual intends to harm an officer or another person.

Like Las Vegas’s changed policy, some police departments allow officers to use chokeholds when the officers perceive their lives are under threat. However, the Model Policy rejects this alternative because of the infrequency with which departments train their officers on the tactic. Even if departments train officers, this training risks officers’ lives—officers have suffered embolic strokes when undergoing training.

Further, the Model Policy makes it clear that it prohibits all uses of chokeholds—including neck restraints—so that vague policy language does not lead to misunderstandings by officers and officers’ use of prohibited chokeholds. For instance, some departments permit neck restraints—where officers block the carotid arteries while keeping the trachea in place—while prohibiting chokeholds—because chokeholds block airways rather than blood. However, the Model Policy acknowledges that both uses of blocking air and blood is lethal to a person and is outright prohibited under the policy.

Clear standards on chokeholds, like those outlined in our Model Policy, are essential to providing a baseline of expectations from the police department and the community. Clear standards dictate how departments should train their officers. Clear standards are also a source of ongoing reference for officers to refresh their understanding of what their departments expect of them. These standards shape the actions of what a reasonable officer can and should do in various situations.

Whether using our Model Policy or similar guidelines, police agencies and communities should work together to form a common understanding of their visions for public safety. These visions should be shaped by information police agencies learn from the most successful police departments across the nation and informed by dialogue with members of communities who are most impacted by policing. While much more is needed to improve public safety, a police department’s use of force policy which considers fair, safe, and equitable values, leading practices, and community voices is essential to achieving fair, safe, and equitable outcomes.

Disclaimer: The facts cited above were assumed to be true based upon the fact finding commission and post-incident report in the Farmer case—as well as public news sources—and have not been evaluated for accuracy. The above analysis reflects the opinions of our staff and is intended for educational purposes and policy discussions.

___________________________________________________

* Additionally, the Model Policy maintains policies on officers’ taser use, speaking techniques, and physical controls. Although we will not discuss Lopera’s continuous use of his taser on Farmer, the use of tasers will be featured during our release of the Model Policy, Chapter 7. Further, we recently discussed the issues of speaking techniques and physical controls. Lopera’s use of verbal commands and hand strikes would fall under these issues—however—we will not revisit those issues in this essay.

Photo graphic source: San Diego Union-Tribune